RABBENU

Our Rabbi

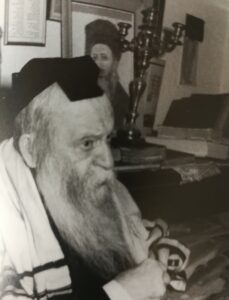

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda HaKohen Kook

By HaRav Shlomo Aviner

Translated from the Hebrew edition by Rabbi Mordechai Tzion

©Copyright 5776

All rights reserved.

Parts of this publication may be translated or transmitted for non-business purposes.

[To learn more about Rav Aviner’s books and writings, or to subscribe to weekly e-mails:

www.ateret.org.il and www.ravaviner.com. To order Rabbenu separately:

Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim

PO BOX 1076

Jerusalem, Israel 91009

Telephone: 02-628-4101

Fax: 02-626-1528

or e-mail: toratravavinerail.com

Table of Contents

Introduction

- Father and Son

- His Younger Years

- Public Affairs

- Eretz Yisrael

- Around the Year

- Personal Traits

- Mitzvot

- Students and Torah Scholars

- Ascending on High

Introduction

Rabbenu, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, wrote a booklet “Le-Shelosha Be-Elul” about the ways and practices of his father, Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook, of blessed memory. Just as we are obligated to learn from the teachings of our great Rabbis, so too are we obligated to learn from their actions and character traits. The entire Torah and Gemara are full of such teachings. The Gemara instructs us regarding the honor, love, and awe of Torah Scholars. The essence of their teachings is certainly the Torah learning and the ethical guidance we receive from them, but there is also the wonderful opportunity to learn rules of proper conduct derived by their exalted example. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was a special emissary of Hashem, sent to us to teach the Nation of Israel the meaning of our national rebirth – the meaning of the ingathered Nation living independently in its Land, according to its Torah. He came to remind us of things we had forgotten.

Now, with the Nation’s rebirth in the Land of Israel, these portions of the Torah are likewise experiencing a rebirth. At first, Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook was alone in his generation. Little by little, like the Redemption itself (Jerusalem Talmud, Berachot, 1:1), disciples and fellow Torah Scholars were attracted to him. So it was with his son, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda. Slowly, students gathered, and more and more people came and listened, until there were dozens, then hundreds, then thousands and hundreds of thousands. Now the Nation is filled with the students of Rabbi Kook, the father, and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, the son.

We pray that this volume will allow a small glimpse into the teachings and the Torah personality of this towering figure, whom students call “Rabbenu,” our Rabbi, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda HaKohen Kook. For the purpose of this translation, to distinguish between father and son, we will use the appellation Rabbi Kook for HaRav Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook, and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, or Rabbenu, for his son. Whenever HaRav Tzvi Yehuda mentioned his father, he would add, “May the memory of the Tzaddik be for a blessing,” or some similar phrase of honor. HaRav Aviner, who compiled this book and whose firsthand recollections form much of its content, also uses expressions of honor when speaking about both Rabbi Kook and about HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, his Rosh Yeshiva for many years. For example, the title “Maran” meaning “our teacher” is always used in reference to Rabbi Kook. To facilitate a more flowing reading, most of these expressions of honored memory have been omitted from this translation. In the Footnotes, the effort was made to record sources whenever possible. The entries, “Iturei Cohanim” and “Iturei Yerushalayim” are monthly bulletins published by Yeshivat Ateret Cohanim, which later became Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim, edited by the Rosh Yeshiva, HaRav Shlomo Aviner. Statements without footnotes are generally taken from the firsthand knowledge of HaRav Aviner.

It must be noted that for the first sixty years of his life, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda remained humbly in the background of his father who was Israel’s Chief Rabbi. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda studied Torah diligently and served his father in any way he could. Even after his father’s passing, he kept out of the public spotlight, unobtrusively preparing his father’s copious writings for publication. He only emerged as the spiritual leader of the generation of national rebirth in Israel when he became the head of the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva in Jerusalem, after the passing of Rabbi Yaakov Moshe Harlop. He continued to head the Yeshiva until his death at the age of ninety. Therefore, many of the recollections recorded in this book are by students who learned at the Yeshiva during the last thirty years of his life, and during his final decade when he was beset by painful illnesses. With great willpower, he remained strong, not ceasing to give classes to his students in his small house on Ovadiah Street in Jerusalem in the neighborhood of Geula.

Rabbi Mordechai Tzion, Book Translator

Chapter One

Father and Son

It was clear to everyone that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was enlightened with his father’s teachings. The thoughts and Torah insights of his father suffused his being. Often when teaching a class, he would read from his father’s writings without adding any commentary of his own. Once he shared with his students a bright illumination regarding Havdalah. “Before the Havdalah blessings we say, ‘You shall draw water with joy out of the wells of salvation,’ (Yeshayahu, 12:3). Concerning this, there is a well-known commentary of Targum Yonaton, which often contains, in addition to the translation, explanations and new insights. He writes, ‘You will receive a new Torah learning from the elite Tzaddikim.’ There is to be a renewal of Torah understanding – a new light that will shine on Zion. There is a teaching of our Sages that the joy of Torah learning has the power to revitalize the Torah. We are instructed to view the Torah each day as if it were new, (Devarim, 26:37, see Rashi). New and joyful. ‘Out of the wells of salvation,’ is explained in the Targum as, ‘From the elite Tzaddikim.’ These are the scholars who occupy themselves with the study of Torah for the sake of Heaven. They are like constantly overflowing fountains, (Avot, 6:2). These sages come to possess a unique character. The wells of salvation are the wells of the Tzaddikim. These unique individuals are the foundations of the world. The influence of their Torah knowledge and their inner wisdom, on its special level, facilitates the Nation’s Salvation and Redemption. We are to joyously receive a new and unique learning from the elite Tzaddikim. There are many Tzaddikim. And there are levels distinguishing them. Among them are elite Tzaddikim whose super-high level of Torah comes down from Heaven to illuminate and accompany, with its special light, the Salvation of the Nation. Just as the soul of the Gaon of Vilna was sent by the Holy One Blessed Be He into the world to illuminate the very first stage of the resettlement of Eretz Yisrael and the Footsteps of Mashiach, it can also be said that the soul of the elite Tzaddik of our time, our teacher and master, my father, HaRav, z’tzal, was sent by Hashem to illuminate the new light on Zion as the Salvation advances and grows. How blessed we are to have merited to be present to share in his light.” 1

Rabbenu said: “In our generation, we have no one to look to for guidance except for the crown of our heads, my father, the Admore of Clal Yisrael. He alone is the great beacon of Redemption who can illuminate new paths of Torah for all of the varying camps in our Nation, from one extreme to the other, and guide them during the Revival in our Land.” 2

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said about his father: “There are revealed Tzaddikim and hidden Tzaddikim. And there are revealed Tzaddikim whose true greatness is kept hidden.”

When people wrote articles about Rabbi Kook in an effort to define him, Rabbenu would respond: “He is who he is.” As if to say that Rabbi Kook was beyond all definition.

When asked who was the Gadol HaDor of the previous generation, Rabbenu would reply decisively, “Abba!” When he was asked if a certain great Rabbi had been the Gadol HaDor, he banged his hand on his desk and declared in a loud voice, “The Gadol HaDor was Abba!”

When Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav was established in the year 5683 (1924), Maran HaRav Kook appointed his son as an instructor, responsible for the spiritual guidance of the students. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda also gave classes in Tanach and Emunah (faith). Israel Chief Rabbi Kook was sometimes present at his son’s shiurim and received great joy from them.

To make it clear that the administration of the yeshiva was to fall into the hands of his son, Rabbi Kook wrote: “Behold, by the power of this letter, I grant authority to my beloved son, who is great in Torah and in the fear of Hashem, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda HaKohen Kook, may he live a long and healthy life, to be in charge of all of the affairs of the yeshiva, and that his words and actions will have all the force as mine, in everything connected to the holy management of the Central Universal Yeshiva in Jerusalem, may the Holy City be completely rebuilt in our time. And may Hashem, may His Name be blessed, be an aid to him in establishing this holy institution on a mighty foundation of Torah that it be a beacon of light to the Jewish Nation and to the world, from the eternal place of Hashem’s Temple, from the everlasting place of our life.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related that when they moved to Jerusalem, his father said to him regarding his writing desk: “Until now, this desk was mine, now it will be yours,” – implying that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was Rabbi Kook’s spiritual continuation.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda also related: “Abba HaRav, may his memory be a blessing, wrote his great response to the Ridvaz on this desk, regarding the Heter Mechirah (lit. “permission to sell” – a halachic method of temporarily selling land in Israel to a non-Jew to enable Jewish farmers to work during the Sabbatical Year). 3 He received the letter of the Ridvaz close to evening. After Ma’ariv, he began to write and continued throughout the night in one flow until his hand hurt.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related that Rabbi Kook once dreamt about King David and King Shlomo. In the morning, he told HaRav Tzvi Yehuda: “This dream is for you,” – meaning that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was the continuation of Rabbi Kook, just as King Shlomo was the continuation of King David.

Referring to his father, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda described himself as one who sits amidst the dust of the feet of the wise (Avot, 1:4). He also said that his voice was his father’s voice. 4

At the dedication of the new Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva building in Kiryat Moshe, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda defined himself, saying: “I am the servant of Avraham,” (Bereshit, 24:34) – meaning that his entire life was committed to his father, whose first name was Avraham.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda did not simply edit his father’s writings, such as correcting spelling mistakes, punctuation, and the like, but engaged in creative editing, in line with the literary independence which his father granted to him.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said that he gave the name “Orot” meaning “Lights,” to his father’s books. 5

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s shemush (serving a Torah scholar) of his father was not only with the ordinary watchfulness and concern, but something great and wondrous. He absorbed his father’s Torah teachings and saintly conduct to the point of the unification of their souls. 6

Rabbi Kook would clarify together with HaRav Tzvi Yehuda the halachic questions which were brought before him. In one of his Responsa from the period of St. Gallen in Switzerland, he writes: “My son, may he live a long life, pointed out…” (“Mishpat Kohen,” pg. 308).

When people would ask Rabbenu to speak about his father, he would say: “It is impossible to talk about Abba HaRav z’tzal. Perhaps it is possible to learn something he wrote.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda had total respect for his father, and he completely nullified himself before him. He had many things of his own to say, but he hid his greatness and never disagreed with his father.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said on 3 Elul, the Yahrtzeit of his father: “There are Torah scholars who are the Gadol HaDor (the great Rabbi of the generation), but Abba z”l was Gadol HaDorot (the great Rabbi of all generations).

One of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s students suggested to him to publish his writings together with the writings of his father. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said: “I am embarrassed to do so.”

When anti-Zionist Zealots from the Old Yishuv came out against Maran HaRav Kook and shamed him, his supporters turned to the Torah Gadol, HaRav Isser Zalman Meltzer, and asked why he did not protest publicly. He answered that if one protests publicly, this will draw more attention to the matter, and it is better not to relate to Lashon Hara at all. Thereby, it will be forgotten. This answer did not find favor in HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s eyes. He insisted that one must respond with strength and decisiveness against the scoffers.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related that when Rabbi Kook appeared before the British court in the matter of Abraham Stavsky (who was accused of murdering Chaim Arlozorov, the leader of the Mapai Party in 1933), the English judge said that he saw in the Chief Rabbi’s eyes, the eyes of a man of war. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda corroborated this statement and said: “Abba z”l was full of kindness and mercy, like the students of Aharon, a lover of peace. But when it was required, he was a man of war.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was opposed to being recorded on tape. A student approached him one day and said: “How wonderful it would be if we had recordings of Maran HaRav Kook z’tzal?! After hearing that argument, he agreed to be taped. 7

A philanthropist asked HaRav Tzvi Yehuda what to donate to the Yeshiva. He did not say dorms, rooms, etc., but rather: “We are lacking chairs.” The man donated folding chairs, and on each one was written: “Yeshivat HaRav Kook.” Rabbenu refused to sit on them: “One does not sit on his father’s name,” he explained.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said: “All of Abba HaRav’s words in ‘Orot,’ ‘Orot Ha-Kodesh,’ ‘Orot Ha-Torah,’ ‘Orot HaRiyah,’ etc., were written with Ruach HaKodesh, like the works of the Maharal. Even though they appear as literary writings, they were all penned with the Divine Spirit.”

A student asked HaRav Tzvi Yehuda: “Why doesn’t HaRav, shlita, write a book with all of his teachings on the Redemption which is unfolding today?” He responded: “I accepted upon myself to publish the books of Abba HaRav z’tzal.” He engaged in the holy endeavor with great self-sacrifice and amazing precision.

After Rabbi Kook ascended on high in the year 5695 (1935), HaRav Tzvi Yehuda secluded himself in his father’s small study several hours a day for seventeen years, organizing the thousands of pages containing his father’s writings. He dedicated most of his time to publishing the halachic writings, in order that the image of Israel’s Chief Rabbi be remembered not only as a philosophical thinker and a communal leader, but to be sure he would be seen in his full Torah standing as an outstanding genius in all spheres of Torah, both the inner Torah and the revealed.

Some students have the ability to draw knowledge from the Torah of their teacher and to transfer it to others to imbibe from its treasures, (see Yoma 28b and Rashi to Bereshit 15:2), but they can only give what they themselves understand. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda attained much more than this. He absorbed the Torah of his father, and it became an inseparable part of his soul and essence. He was thus able to lead a generation which had new problems which did not exist at the time of his father. He was able to tell us what Maran HaRav Kook would have said in a given situation. Anyone who looked at HaRav Tzvi Yehuda actually saw Rabbi Kook in his face.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said: “There are people who do not know what are Gan Eden and Gehinom: I can feel Gehinom in this world on account of the distance from Abba (now that he is no longer among us).”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda confided: “I do not understand how the world exists without my Father.”

When HaRav Tzvi Yehuda rose to speak on 3 Elul, the Yahrtzeit of his father, he would enwrap himself completely with his tallit. He leaned on the podium and cried. It was clear from his words the intimate connection he had even now with his father, as if Rabbi Kook had ascended on high at that very moment.

Regarding difficult matters of the Yeshiva, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would say: “I am taking counsel with Abba HaRav z’tzal.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was once walking in the old Yeshiva building. When he entered the little room where Rabbi Kook had learned, he stopped and not only kissed the mezuzah, but also kissed the door.

“I heard from HaRav Natan Ra’anan, of blessed memory, that there was once a memorial exhibition about Rabbi Kook at a university. He approached HaRav Tzvi Yehuda and told him about the exhibition, but Rabbenu refused to go, saying, “Although they are presenting his wisdom there, his fear of Hashem will not be seen there, and his towering Emunah will not be represented. Why then should we go there?!” 8

Who is the Host?

Rabbi Kook would occasionally travel from the city of Zoimel, where he was the Rabbi of the community, to visit his parents in his hometown of Geriva. On the way to Geriva, he would pass through Dvinsk, where the Torah giant of the generation, Rabbi Meir Simcha, the author of the “Ohr Sameach,” was the city’s Chief Rabbi. Maran HaRav Kook would say that the “Ohr Sameach” was the central Torah giant of the generation since he not only knew Torah, but that he created Torah, meaning his abundant new Torah insights and Chiddushim. Accordingly, when Rabbi Kook passed through Dvinsk, he would visit the house of Rabbi Meir Simcha in order to discuss Torah. He once visited the renowned scholar and found him standing by a table, learning a sefer of the Rambam, with many other books open before him. They greeted one another and immediately began discussing matters of Torah. Their scholarly exchanges continued for an extended period – the entire time standing up! When the flood of Torah ceased, Rabbi Meir Simcha realized that he did not invite his guest to sit down. Seeking to rectify the situation, he immediately invited Rabbi Kook to sit. Then Rabbi Meir Simcha began to tell a story:

Franz Joseph II, the Kaiser of Austria-Hungary, was known as a benevolent king who would periodically travel around like one of the commoners, without any royal trappings, so that no one would know who he was. On one of his excursions, the king once entered the National Library in Vienna. Despite all of his efforts to hide himself, everyone recognized him and stood in his honor, except for one person who remained seated in his place, deeply immersed in the book he was studying. He was the brilliant author of “Yad HaMelech,” the Rabbi of Brody in Galicia. The king took notice of the man who continued to study, not taking his eyes off of the book. He was so engrossed in his learning that he didn’t notice anything around him. Realizing that the fellow meant no disrespect, the king approached him and began a conversation. All of the people in the library were startled.

The king asked him: “Who are you?”

“I am the Rabbi of Brody,” the man responded.

“If I come to Brody, may I visit your home?” the king asked.

The “Yad HaMelech” replied: “Certainly, it would be my great honor!”

Time passed and the incident was nearly forgotten. Many years later, the king, dressed in his royal attire, suddenly entered the house of the Rabbi of Brody. At that moment, the Rabbi was standing next to his bookshelf, engrossed in a book. Just like the first time, the king approached him. The Rabbi was so surprised, he forgot to ask the guest to sit. Standing, they began to talk.

The king asked: “Rabbi of Brody, is the custom of receiving guests while standing based on the Talmud and the customs of the Jewish People?” Though the clever Rabbi had been caught off guard, he answered immediately: “G-d forbid! We follow the path of our forefathers who taught us that ‘Welcoming guests is greater than receiving the Divine Presence,’ but our proper etiquette is that the host asks the guest to sit, and the king, wherever he is – he is the host!”

By telling this story, the great “Ohr Sameach” hoped to appease his guest, the young Rabbi of Zoimel, whom he did not ask to sit, by referring to him as the king! HaRav Tzvi Yehuda added that, in his later years, Rabbi Kook would tell this story on Purim, but on account of his great humility, he did not relate all of the details of the tale. He did not say to whom the “Ohr Sameach” told the story, and he did not relate who had been the guest. Only after Rabbi Kook passed away did this detail become known – it was Rabbi Kook himself who Rabbi Meir Simcha had appeased by comparing him to a king. 9

HaRav Yosef Buxbaum, the editor of the journal “Moriah,” had a very close relationship with HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, following the lead of HaGaon HaRav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would give him letters which great Rabbis wrote to Rabbi Kook, in order to publish them in “Moriah.” HaRav Buxbaum would often visit HaRav Tzvi Yehuda. And when a baby boy was born to him, he asked HaRav Tzvi Yehuda to serve as the Kohen at the Pidyon HaBen.

It once happened that one of the editors of the “Otzar Mefarshei HaTalmud” (Treasury of Talmudic Commentators) included a ruling of Rabbi Kook, but another editor removed it. HaRav Buxbaum asked him why – was it because he found a difficulty with it requiring further clarification? He answered: “I didn’t even look into the issue. I just think that a ruling of Rabbi Kook is not appropriate for ‘Otzar Mefarshei HaTalmud.'” HaRav Buxbaum said to him: “From this moment, you are fired!” The editor did not accept his decision, so they went to HaGaon HaRav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv for arbitration. HaRav Elyashiv was shocked and said to the editor: “Did you know HaRav Kook?! You should know – he was holy. He did not belong to our generation, and in his generation, they did not properly understand him. Reb Yosef was certainly permitted to fire you. I would have done the same thing.” 10

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related that his father would go to relax on Mount Carmel in Haifa because of a physical ailment. HaGaon HaRav Isser Zalman Meltzer, Rosh Yeshiva of Etz Chaim, once happened to meet him there. When he returned, he said: “I merited to spend time with a Jew who does not spend a moment devoid of holiness.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda remarked that HaRav Meltzer said: “If only our Neilah prayer on Yom Kippur was like Rabbi Kook’s Mincha on a Friday afternoon.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would not pass through the Zichron Moshe neighborhood in Jerusalem since, in the past, they had burned an effigy of his father there. 11

When HaRav Yosef Chaim Zonenfeld ascended on high, Rabbi Kook wanted to attend the funeral, but HaRav Tzvi Yehuda forcefully prevented him, saying that he would lay down in front of the wheels of their car and stop him from going, out of a fear that the Zealots would attack him. 12 There were actual cases when Zealots physically attacked Rabbi Kook.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would go to hear Divrei Torah from the Brisker Rav (HaGriz), HaRav Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik – and when he was there, the Zealots (extreme anti-Zionists) would insult him. If HaRav Tzvi Yehuda had heard insults about Maran HaRav Kook he would not have remained silent, but he was prepared to ignore their rebuke of him for the sake of hearing the Brisker Rav. When HaRav Shabatai Shmueli, the Yeshiva’s secretary, heard about this, he was shaken and pleaded with HaRav Tzvi Yehuda to stop attending the Torah lectures. HaRav Avraham Shapira also attempted to convince HaRav Tzvi Yehuda to stop, but he wanted to hear Divrei Torah from HaGriz. HaRav Shmueli and HaRav Shapira requested that Reb Aryeh Levin – who also frequented there – speak with HaRav Tzvi Yehuda. He agreed and said to him: “Reb Tzvi Yehuda, you must cease going there. The insults you suffer do not bring honor to the Torah. It is also insulting to the memory of your father, z’tzal.” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda tried to justify continuing his visits by saying that their denigration did not affect him, and that HaGriz is one of the great Rabbis of the generation, etc., but Reb Aryeh interrupted him and, uncharacteristically, said harsh things about the Zealots. When HaRav Tzvi Yehuda heard this from the holy mouth of the Tzaddik Reb Aryeh, he did not return, even though there was a great lost in not hearing the Torah lectures of HaGriz. 13

Once, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda had a question on the Rambam. He went to clarify it with the Brisker Rav and HaRav Isser Zalman Meltzer, since they both authored works on the Rambam. 14

HaRav Eliezer Melamed wrote in the newspaper Besheva: “After the anti-Zionist Brisker Rav – HaRav Yitzchak Zev Soloveitchik – harshly opposed the building of Heichal Shlomo (the building of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel), HaRav Yehuda Leib Maimon wrote a scathing criticism about him. My father and teacher, HaRav Zalman Melamed, told me that he went to speak with HaRav Tzvi Yehuda about this and asked him: ‘When a lesser Rabbi disagrees with a greater Rabbi, isn’t this an impingement on the honor of the Torah and shaming a Torah scholar?’ HaRav Tzvi Yehuda answered: ‘Certainly.’ HaRav Zalman Melamed then asked about HaRav Maimon: ‘How can he so harshly disagree with the Brisker Rav?’ HaRav Tzvi Yehuda answered: ‘But he is right’ (meaning in regards to the dispute about Heichal Shlomo and similar issues regarding the Israel Chief Rabbinate).

A Torah Scholar was delivering a eulogy for a great Rabbi and he spoke about Rabbi Kook without explicitly citing his name. After mentioning his greatness, he added “But his love of Israel is contrary to normal behavior,” (see Bereshit Rabbah 55:11; and Rashi to Bereshit 22:3). HaRav Tzvi Yehuda explained that his father’s love of Israel was not love in the usual sense, but came from a deep understanding of Hashem’s love of Israel, from which his own love flowed. And regarding the Torah scholar’s words, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda cited the teaching: “One who prays: ‘May Your mercy reach the bird’s nest,’ we silence him,” meaning the value of the commandment “shiluach haken” is far beyond the concept of mercy,” (Berachot 33B). 15

Time and time again, the Rosh Yeshiva, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, repeated to his students the vital importance of studying the books of Rabbi Kook, and he insisted that a person had to learn the book, “Orot,” day and night. Even if he didn’t understand it, one needed to relearn it a thousand times – maybe after such an effort the student would merit to comprehend something. 16

HaRav Shlomo Goren, Chief Rabbi of Israel, said that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda carried out the vision of his father. Rabbi Kook envisioned the resettlement of the Nation in Israel, and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda brought the vision down to earth. Rabbi Kook taught and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda implemented his words. He raised up a generation of Torah scholars and rebuilders of the Nation and the Land.

HaRav Shlomo Goren, Chief Rabbi of Israel, said that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda carried out the vision of his father. Rabbi Kook envisioned the resettlement of the Nation in Israel, and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda brought the vision down to earth. Rabbi Kook taught and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda implemented his words. He raised up a generation of Torah scholars and rebuilders of the Nation and the Land.

Sometimes, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would awaken in the middle of the night and say, “My father spoke to me just now and told me this and that.”

Rabbenu stated, “I am the absolute continuation of my father.” 17 He called his book, “L’Netivot Yisrael,” (To Pathways of Israel), implying that the pathways he enumerated were the ways to reach the “Lights” of his father’s teachings, since they were the goal and destination – the treasure at the end of the road. He called his father, “The Living Lion,” saying that in the Upper World of Souls, he still guided us and kept a watch upon our doings.

Many things which appear in the writings of Rabbi Kook in an abstract manner, such as the inner workings of Segulat Yisrael and Geulat Yisrael, find concrete expression in the teachings and deeds of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, often during times of great challenges to the Nation.

A new student arrived to the yeshiva in the month of Elul and began to study. After a week, he told HaRav Tzvi Yehuda that he felt nothing special about the place, and that he had decided to leave and study in Kfar Hasidim. Rabbenu told him not to leave. The student said that wanted to feel somthing special since it was the month of Elul and therefore he was leaving. Again, Rabbenu told him not to go. Nonetheless, the stubborn student didn’t listen and left the yeshiva. As soon as he reached Kfar Hasidim he developed stomach pains which forced him to go home. When he felt better after a week, he returned to Kfar Hasidim, but fell ill with some other ailment. The entire month until Yom Kippur, he couldn’t learn. After Sukkot, he returned to Mercaz HaRav and told the Rosh Yeshiva everything that had happened. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda confided to him: “When my father was alive, everything he would say would come to pass. With me, I don’t have the same power, but I certainly possess a spark of my Father’s holiness.” Ever since then, the student made HaRav Tzvi Yehuda his Rabbi. For years he learned in the yeshiva and became an outstanding Talmid Chacham.

It once happened that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda went to daven in a shul in Meah Shearim with one of his students. After the davening, the student said to HaRav Tzvi Yehuda: “Did HaRav notice that they did not count us in the minyan?” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda responded, “I noticed.” Then, he explained to the student one of the reasons why the Zealot faction of the Ultra-Haredi community in Jerusalem was fiercely opposed to the “Zionist” Chief Rabbi. “Some people once requested that I suggest to Abba HaRav z”l that he omit the section discussing exercise from his book ‘Orot.’ Abba HaRav z”l explained to me that to do so would not be in the category of fear of Hashem, but rather fear of flesh and blood. From that moment on, I stopped fearing flesh and blood. You see, in chapter 34 of ”Orot HaTechiyah,” my father wrote that the merits of physical exercise by the young pioneers in the Land of Israel are similar to the merits of reciting Tehillim and the mystical unifications of the Kabbalists. The Ultra-religious Jews of the Old Yishuv in Jerusalem waged war with Maran HaRav Kook over this idea. That is why, when they recognized me, they didn’t count us as part of the minyan.” 18

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related: “My father, of blessed memory, needed glasses, but he did not wear them. He explained: ‘For a Jew, the essence is to learn Torah, and I am able to do so without glasses. It is not so terrible that I cannot see so well at a distance.’ When my father was chosen as Chief Rabbi of the Land of Israel, he was forced to wear glasses, since, he said, the British Consulate was across the street from the building of the Chief Rabbinate, and one must properly relate to these dignitaries by seeing them well, even at a distance. 19

Rabbi Kook’s Room

Once after davening in the original building which housed the yeshiva, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda went the room where his father most often learned. Before entering, he removed his Tefillin in the hallway. He expained: “It is an explicit Halachah in the Shulchan Aruch that it is forbidden to remove one’s Tefillin in the presence of his Rabbi.”

Once when HaRav Tzvi Yehuda entered that room, he not only kissed the mezuzah as is customary, but he also kissed the doorposts. He said that Beit HaRav, which was Rabbi Kook’s house and, for a time, the site of Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav, still retains its holiness.

On one of the summer days in 5708, during the War of Independence, only two students – HaRav Yosef Kapach and HaRav Glazer – were learning in the old building of the Yeshiva, together with HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, who did not refrain from coming to the Yeshiva even during times of danger. There was a huge explosive near the Yeshiva which killed two women. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda brought the two students with him into Rabbi Kook’s room, pointed to his chair and announced: “In merit of the one who sat in this chair nothing will happen here!” 20

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related that his father, of blessed memory, once received a long letter which included reasons to be lenient in certain forms of electricity used on Shabbat and Yom Tov. He briefly responded that it is forbidden since electricity is fire. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda asked his father about this, since his usual way was to respond based on the length of the letter (i.e. if the letter was lengthy, he would respond at length), but here he did not respond in kind. Rabbi Kook responded: “When issues are clear, there is no reason to be lengthy.” 21

Rabbi Binyamin Levin, grandson of Rav Aryeh Levin, related: “My father, HaRav Raphael Levine, and HaRav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach studied together as children at Yeshivat Etz Chaim on Jaffe Road. Sometimes on Shabbat they would learn in the beit midrash. My father and Rav Auerbach both told me that sometimes they would close the Gemara and walk across Jaffe Road to the home of Rabbi Kook. They would go upstairs to his home, taking turns for a moment to peek through the keyhole to watch Rabbi Kook intensely absorbed in his studies. They said that those few minutes watch the great Rabbi’s face radiating with holiness gave them the desire to return immediately to their learning to become great Torah scholars. 22

The Words Engraved on Rabbi Kook’s Tombstone

HaRav Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook

Born on 16 Elul 5625

Ascended to the Land of Israel on 28 Iyar 5664

Ascended to Jerusalem on 3 Elul 5679

Ascended to Heaven on 3 Elul 5695

Maran HaRav Kook’s Grave

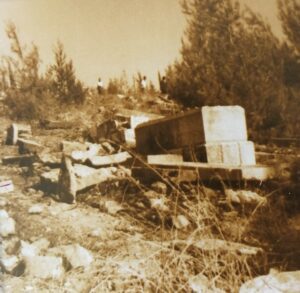

Rabbi Yaakov Filber relates that Rabbi Kook’s grave on the Mount of Olives remained completely intact during the period between of the War of Independence and the Six-Day War when the area was under Jordanian control. While most of the graves were vandalized, and the tombstones were uprooted by the Arabs and used for paving roads, Rabbi Kook’s grave remained untouched. Rabbi Filber heard from reliable sources that every time a Jordanian tractor came to reach the grave, the tractor would flip over. The Jordanians were struck by the holiness of the grave and left it alone. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda filled in the details. While everything around his father’s gravesite was bombed out or destroyed, his gravestone remained whole. An Arab worker related that they received special instructions from their superiors not to damage the grave in any way. 23

Chapter Two

Early Years

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was born in Zoimel, in the area of Kovno in Lithuania, on the night of Pesach in the year 5651 (1891) to Maran HaRav Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook and HaRabbanit Raiza Rivka. With all of his great humility, he understood his worth and would say: “My soul appeared on the night of the Seder.”

HaRabbanit Raiza Rivka was the second wife of Rabbi Kook, whose first wife, Rabbanit Batsheva Alta, daughter of the Aderet, died in a plague when Rabbi Kook was serving as the Rabbi of Zoimel. At the time, their daughter, Frieda Chana, was one and a half. The Aderet, HaRav Eliyahu David Rabinowitz-Te’omim, the Rabbi of Ponovezh, wanted his son-in-law to remarry, and he suggested that he wed Raiza Rivka, the daughter of his late twin brother, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda Rabinowitz-Te’omim, who has been the Rabbi of Ragoli. The Aderet said to Rabbi Kook: “It is a pity for me if, with the loss of my daughter, I also lose you from being a member of my family. Marry my brother’s daughter and you will be my son like before.” 1

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was named after his mother’s late father. Two sisters were born from his father’s second marriage as well – Batya Miriam and Esther Yael.

The Kook family moved to Boisk, next to Riga, where Rabbi Kook was appointed to lead the community. Tzvi Yehuda learned Gemara from HaRav Reuven Gutfried (Yedidya), the son-in-law of Rabbi Yoel Moshe Solomon, and from HaRav Binyamin Menasheh Levin, author of “Otzar HaGeonim,” who became HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s personal teacher. 2

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda learned Tanach from HaRav Moshe Dr. Zeidel, who, like HaRav Levin, came to Boisk to absorb the aura of abundant holiness which surrounded Rabbi Kook. The essence of his learning, however, was from his father.

Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook was appointed Chief Rabbi of Jaffa and the surrounding settlements (Petach Tikva, Rishon Le’Tzion, Gedera, Rechovot, etc.) in the year 5664 (1904). After lengthy negotiations with the community, the final letter with the travel expenses arrived. Rabbi Kook left a note for his daughter to pick up the letter. But HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, out of his love for Eretz Yisrael, rushed to get the epistle himself, in order to receive a letter from the Holy Land. He made Aliyah with his family shortly after his bar mitzvah. Every year, like his father, he would celebrate the date of his arrival in the Promised Land, the 28th of Iyar, which later became the day that Jerusalem was liberated during the Six Day War.

When HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was fifteen, he ascended to Yerushalayim to learn in Yeshivat Torat Chaim in the Old City. Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank, Rabbi of Yerushalayim; Rav Yitzchak Herzog, Chief Rabbi of Israel; and Rav Aryeh Levin, the Tzaddik of Yerushalayim, also learned in the famous Torat Chaim Yeshiva.

Yeshivat Torat Chaim

During the War of Independence, Jerusalem fell into enemy hands. But a miracle occurred. Unlike all of the other synagogues and yeshivot in the Old City, which were destroyed and plundered by the Arabs, the Torat Chaim Yeshiva was spared. The Arab who lived below, one of the righteous non-Jews among the nations, locked the beit midrash and claimed that the building was his, thereby preventing rioters and plunderers from entering. Out of all the yeshivot in the Old City, this building alone (and its holy content!) was saved from the Arabs, similar to the jug of oil found in Temple with the seal of the Kohan HaGadol still intact. The building is located in what is called the Moslem Quarter today, but in the years that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda had studied there, it had been a thriving Jewish neighborhood known as the Western Wall Quarter until the Arab pogroms in the 1930’s forced the Jews to flee. When the Old City was liberated during the Six Day War, no one rushed to resettle the once famous Jewish neighborhood, nor endeavored to discover the fate of the large synagogues and yeshivot which had been the pearls of the community.

On Ta’anit Esther 5728, after the Six-Day War, the students of the Mercaz HaRav Yeshiva went to daven at the Kotel. A student of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda who had a car took him home as usual. It was in the middle of the day and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda asked: “Don’t you have a class now?” He answered: “Yes, but our Sages say that serving Torah Scholars is greater than learning.” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda agreed by his silence. When they were near Sha’ar Shechem (the Damascus Gate), HaRav Tzvi Yehuda asked to stop. Without saying a word, Rabbenu got out of the car and he began to quickly march toward the entrance to the Moslem Quarter. Two students escorted the 78-year-old Rabbi, one on each side, running to keep pace with him. He momentarily stopped where the street splits, then continued along HaGai Street. Meeting someone he knew, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda stopped and exchanged a few words until HaRav Tzvi Yehuda pointed toward a particular building not far away. The man said: “I am certain that it is there,” pointing to the entrance of Yeshivat Torat Chaim (which is now the location of Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim – formerly Ateret Cohanim, where I have served as Rosh Yeshiva for the past thirty years). HaRav Tzvi Yehuda ran in the direction of the Yeshiva building and ascended the long flight of stone stairs to the second floor. The students asked him what he was doing, but he didn’t answer. He stopped in the narrow second-floor hallway in front of a window, held the bars, pulled himself up as much as he could, and looked into the beit midrash for a long minute. When he let himself down, the students again inquired about the mystery. “I learned Torah here when I was young,” he responded. “This was the Yeshiva of Rabbi Epstein and Rabbi Winograd. My father sent me to learn Torah here.” Inside the old study hall, it was possible to make out some shtenders and tables with books piled on them, covered with centimeters of gray dust which had accumulated over the years since the Yeshiva had been abandoned. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was deeply moved. He uttered some Psalms of praise and then headed back to the car. On the way, he related stories about his time in the Yeshiva. Once, he recalled, the Rabbis complained to the Turkish authorities that the nearby muezzin, which loudly called Arabs to prayer, was bothering the learning of the students. As a result, the Turkish silenced the muezzin during the classes in the Yeshiva.

Finding a Place to Learn

Returning to Jaffa, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda aided his father with the many public and private matters which he dealt with as Chief Rabbi of Jaffa and the surrounding settlements. When it became clear that this involvement turned detrimental to his Torah learning, he moved back to the Old City of Jerusalem and sheltered himself in Yeshivat Porat Yosef. Also there, because he was the son of the well-known Rabbi Kook, he found it difficult to concentrate on his studies. Consequently, he considered traveling to one of the major yeshivot outside of Israel. Consulting with his father and HaRav Binyamin Menasheh Levin, he decided to travel to Halberstadt in Germany in order to learn and teach Torah to a group of young men. His good friend, HaRav Dr. Moshe Auerbach, the principle of the “Netzach Yisrael” School in Petach Tivkah, also advised him to go and learn with his brother HaRav Dr. Yitzchak Auerbach, the Rav of Halberstadt. While he was in there, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda taught Gemara, Kuzari, and Tanach to the students.

When World War One broke out, Rabbi Kook, who had been invited to the influential Agudat Yisrael conference in Germany, was not able to return to Israel. He was forced to stay in Switzerland for an extended period since all routes of transportation were closed. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related:

“During that period of isolation in Switzerland, I learned the entire Torah with Abba: the Babylonian Talmud, the Jerusalem Talmud, Rambam, Tur – a few times – which we would not have been able to learn together in one hundred years (while his father was exceedingly busy with Rabbinical duties in Jaffa).”

After the World War, at the end of 5680 (1921), HaRav Tzvi Yehuda traveled once again to Europe as an emissary of his father, in order to participate in the annual Agudat Yisrael conference. His goal was to explain to the leading Rabbis and Chasidic Rebbes the goal of the “Degel Yerushalayim” Movement which Rabbi Kook established to inject a spirit of Torah within the general Zionist Movement. He hoped to enlist Torah-observant Jews in the movement in order to strengthen the spiritual foundation which was, Rabbi Kook declared, inherent in the ingathering of the exiles and the rebuilding of the Israelite Nation in the Holy Land.

During one of his trips, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda met the daughter of HaRav Yehuda Leib Hutner of Warsaw, HaRav Yehoshua Hutner’s sister, for the sake of getting married. When he saw her, he immediately felt that this was his soul-mate. They learned the entire book “Orot” together, while it was still in booklet form, before their marriage and married in Warsaw on the 26th day of Shevat, 5682.

HaRabbanit Chavah Leah possessed both Torah wisdom and general knowledge, and was involved with education and social work. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said that she had a precise sense of people, and many times after he spoke with his students, she would say: “You should not expend so much energy on student B, but it is worthwhile to give student A more attention.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related that on one extremely cold winter day, HaRabbanit went out to bring firewood to the poor in the Old City of Jerusalem. He begged her not to go out of the house. She nonetheless went and returned with a chill that developed into pneumonia, from which she died in 5704. Rav Hutner, her brother-in-law, revealed that the doctor gave her a shot, not knowing that she had a heart problem. Tragically, her reaction to the injection proved fatal. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, however, would not put the blame on the doctor.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s sister, HaRabbanit Batya Miriam, encouraged him to remarry, as did his former mother-in-law, but he refused. The wife of the Nazir also suggested a match. He responded: “You are right, but I am unable to.” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda never remarried. We do not know the reason.

Until his last day, a picture of his wife, taken before their wedding, hung over HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s bed, which was a clear sign to his students that this was an expression of their eternal connection. 3

Even forty years after she ascended on high, Rabbenu would speak about her with emotion and tears, as if she had died that day. 4

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda did not recite “Eishet Chayil” before Kiddush on Shabbat night. When a student asked him about this, he somberly responded: “I do not have an ‘Eishet Chayil’ (Woman of Valor)” – since HaRabbanit Chavah Leah had died.

After his wife’s death, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would regularly eat Shabbat meals at his sister and brother-in-law’s house – Batya Miriam and HaRav Shalom Natan Ra’anan. Then, suddenly, he stopped coming on Shabbat night. When they asked him the reason, he responded that his wife appeared to him in a dream and asked why he was leaving her alone in the house on Shabbat. 5

Chapter Three

Public Affairs

The Struggle against Missionaries

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda waged war against the missionaries who tried to gain a stronghold in Israel. He was a leader of the struggle, and the headquarters of the campaign was centered in his house. Everyone in the country knew that the most attentive ear was to be found with our Rosh Yeshiva. He urged active opposition, and sought to enlist others to join the cause.

A Christian missionary from Tiberia would come to Jerusalem regularly, and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would welcome him as a guest in his small apartment in the Geula neighborhood of Meah Shaarim. Students told the Rosh Yeshiva that they could not tolerate the fellow, but HaRav Tzvi Yehuda sacrificed himself for this cause (by inviting him), because this missionary, out of endearment, would relate to him all of the ins-and-outs of the missionary activity in the country. Rabbenu would pass this information on to “Chever HaPe’ilim” – an organization which worked to protect the public against missionaries. As a result, many people were saved.

A protest against the missionaries was organized by one of the leading students of the Yeshiva. The protest was illegal, and the protesters were arrested. The next morning, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s voice thundered against the organizer: “In my darkest nightmare, I never dreamed about violating the law.” After the court verdict of guilty, the protesting students decided not to pay the fine and to be incarcerated. They were imprisoned in the Damon Jail on Mount Carmel. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda went to visit them. Upon entering the mess hall where they were eating, all of the students jumped up from their chairs in surprise. After everyone calmed down, he said, “One who sees houses of Israel in their inhabited state says: ‘Blessed is the One who establishes the widow’s boundary,’” (Berachot 58B). He generally recited this blessing immediately upon arrival at a new community, but when there was the possibility of “publicizing the miracle” when a large group of people would gather to greet him, he would delay the blessing. This time, he said: “My visit to this place is not because of joyous circumstances, but we must remember that even a Jewish jail is an expression of the sovereignty of the Nation of Israel over its Land.” And he continued to recite the blessing with Hashem’s Name and Kingship: “Blessed are You…who establishes the widow’s boundary.” 1

A student related: “During one of the years when the production of Handel’s “Messiah” (a Christian symphony) was playing in concert in Jerusalem’s National Hall (‘Binyanei HaUmah’), HaRav Tzvi Yehuda tried to have the concert canceled, insisting that it certainly had no justification to be held in an official public building. Rabbenu requested that I go with him to the house of HaRav David Kohen – “HaNazir” – since there was a telephone there, and arrange for him to speak with Chaim Moshe Shapira and Yosef Burg, who were members of the Knesset from the National Religious Party. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda asked them to work to cancel the concert. They answered that canceling the event was not possible. Not satisfied with their response, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda sent students to disrupt the concert. He praised the students who staged a protest inside the hall at the time of the concert of “Messiah” and particularly the student who jumped onto the stage yelling how terrible an affront the event was to the Jewish People. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda related that the police commander told him afterwards: “Your young men are gold, and the one who got up on the stage deserves a medal.” After the concert-goers dispersed, the protesters from the Yeshiva and a squadron of police officers remained in the hall. The officers asked the protesters to leave the building, announcing that the show was over. One of the students arose and lectured them about the grave act which had transpired, declaring they would not leave the hall. When the officers’ patience ran out, they took three of the Yeshiva students to jail. Gradually, the rest of them left the building. The next day, students turned to HaRav Tzvi Yehuda and asked him to work to free those who were imprisoned. Rabbenu replied: ‘I do not understand why they did not disperse according to the police’s request after the concert ended. We were not there to protest against the police, but against the concert!'”

Hebrew Date

Rabbenu was particular that one should not write the Christian date. If he was invited to a wedding and the Christian date appeared on the invitation, he would not attend. 2

In a letter, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda highlighted his opposition to the use of Christian dates by referring to one of his father’s correspondences. Rabbi Kook wrote, quoting the Rambam: “I received your letter with a date which I do not know or understand, since I am unfamiliar with the counting of time from the year of the birth of ‘that sinner of Israel whom the non-Jews made into idol worship, who practiced sorcery, enticed and led Israel astray (Sanhedrin 107A), who caused Israel to be destroyed by the sword and its remnants scattered in humiliation, who exchanged the Torah (for a doctrine of falsehood), and deceived the majority of the world to serve a G-d other than Hashem,’” (Rambam, Hilchot Melachim, Ch. 11). 3

A Rabbi of a community outside of Israel visited HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, who asked him about the date of a particular event. The guest answered with the date according to the Christian count. Rabbenu said: “Excuse me, I did not hear.” The visitor raised his voice and repeated his words. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda again said to him: “I did not hear.” This exchange was repeated a third time. By the fourth time, the guest understood the problem, and he mentioned the Hebrew date. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda smiled, and the guest promptly apologized.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda agreed to participate in an important ceremony on behalf of the Municipality of Jerusalem, but when he saw that only the Christian date, and not the Hebrew date was on the announcement, he refused to attend, and all of the attempts to persuade him otherwise did not help.

When the ruling of Rav Ovadiah Yosef was publicized that there is no prohibition in using the Christian date, and that those who use it have on whom to rely, (“Shut Yabia Omer,” Vol. 3, Yoreh Deah, #9), HaRav Tzvi Yehuda expressed deep sorrow. 4

Protest Over Autopsies

There was no need for HaRav Tzvi Yehuda to explain his opposition to autopsies, yet he related that Maran HaRav Kook once heard that in opposition to the Halachah an autopsy was to be conducted on a woman who was alone when she died. He called the hospital and said: “This is the Chief Rabbi of Israel. I am a Kohen. It is forbidden for a Kohen to become impure by coming in contact with a corpse, but if need be, I will come and become impure in order to bury this person since there is no one else to attend to it, something known as a ‘met mitzvah’ which even a Kohen is obligated to do.” He was suggesting that, if necessary, he himself would come to bury the body, rather than allow it to be desecrated.

Herzl

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was well known for his declaration that the majority of the world’s Torah Giants did not oppose Zionism. Once, one of the students at the Yeshiva said that he himself would not dare make such a statement in the vicinity of the Holy Ark. The student’s words made their way to the ears of the Rosh Yeshiva. Immediately, he ran to the Yeshiva, opened up the Holy Ark containing the Torah Scrolls and declared, “Whoever says that the majority of Torah Giants opposed Zionism is a liar. The truth is that Zionism was a new movement, and most of the leading Rabbis were uncertain how to relate to it. Most of those who did take a stand were actually in favor of Zionism. Only two Rabbis opposed it: Rabbi Chaim of Brisk and Rabbi David Friedman.” I asked the Rosh Yeshiva why they stood in opposition. He replied, “Were there not sufficient reasons for opposing?”

In his youth, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda learned in Yeshivat Torat Chaim in the Old City (in the building where Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalayim is now located). Many great Rabbinic leaders learned there, such as Jerusalem’s Chief Rabbi, HaRav Tzvi Pesach Frank, HaRav Aryeh Levin, and HaRav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv. Rabbenu related that HaRav Yitzchak Nissenbaum, who was the secretary and right-hand man of HaRav Smuel Mohilever, one of the founders of the Religious-Zionist movement called “Hibat Tzion,” was invited to give the main Derashah one Shabbat. This fact testifies that the Rosh Yeshiva, HaRav Yitzchak Winograd, did not fear the zealots of Jerusalem, who fiercely opposed the Zionist Movement. Hundreds of people, include many wearing shtreimels, filled the beit midrash and listened to the gifted speaker. When he began discussing the foundations of Religious-Zionism, a loud voice interrupted his words, yelling out: “Is that what Herzl also says?” This caused a commotion among the listeners. Rav Winograd ascended the bima, silenced the crowd, expressed his dismay, and demanded that the brazen person leave the Yeshiva. Rav Nissenbaum adds in his book, “Alai Chaldi,” that he saw arms lifting the man above the crowd and taking him out through the window. At Seudah Shelishit, Rav Winograd told him that one of the zealots had come to him on Friday, demanding that he not allow a talk about impure Zionism in the holy Yeshiva. Rav Winograd responded that the Yeshiva was under his authority, and anyone who disturbed the talk would be paid back in kind. He then hired two guards who stood near the window, ready to deal with troublemakers. When the brazen man began to yell, the young people next to him grabbed his arms and legs and lifted him up to the guards. The zealot’s comrades were shocked and did not dare to create any further disturbance.

It is well known that along with pictures of the Netziv, the Aderet, Rabbi Kook, and others, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda had a picture of Herzl hanging in his home.

Rav Avraham Romer related: “The picture of Herzl once disappeared from HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s house, and there was a suspicion that some visitor to the house wanted ‘to teach him a lesson.’ When I suggested that perhaps the picture fell behind the desk, he permitted me to look there. When I found the picture, he was extremely happy and told me wondrous stories about Herzl and some of the remarkable things he did to advance the acceptance of Zionism. He repeated the opinion of Reb Aharon Marcus, z”l, who said that Herzl was a descendant of Mahari Titzak (a famous Rabbi) and that he descended from a Sefardic family. 5

Rav Tzvi Yehuda lived in a small, modest apartment in the neighborhood of Geula, not far from Meah Sha’arim. When a certain neighbor would come to HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s house, he would flip over the picture of Herzl. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda once caught him in the act and wryly asked him: “Why are you doing this? Doesn’t he have all five corners of his beard, according to the Torah?” 6

A student of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda saw Herzl’s picture hanging in the room where the Rosh Yeshiva taught classes in his house, amongst pictures of our great Rabbis. He asked for an explanation, and HaRav Tzvi Yehuda gave an entire class on the fact that Herzl was the shaliach of the Master of the Universe in the holy tasks of returning the outcast exiles to Zion in our time, and in returning Jewish sovereignty over Eretz Yisrael, whether we liked the fact or not.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda encouraged one of his students who was a baal t’shuva (a Jew who returned to being observant) to read Herzl’s diaries. 7

With the Leaders of the State

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda wrote: “…Just as one who vilifies the Army of Israel is like one who vilifies the Armies of the Living G-d (Shmuel, 1, 17:26), so too, one who vilifies the Kingship (the legal ruling authority) of Israel is like one who vilifies the Kingdom of Hashem. This honor may not be waived (Kiddushin 32B). According to the words of our Sages (Jerusalem Talmud, Yevamot, chap. 16), even Aviyah, King of Yehuda, was punished by Hashem on account of his vilifying the Kingship in public – in the military campaign against Yerovam ben Navat, King of Israel. And Eliyahu the Prophet acted in a respectful manner – albeit his words of harsh rebuke – to Achav, King of Israel. Based on this, our Sages established (Menachot 98A) the obligation for all people throughout the generations to act in this manner of respect (toward the government of Israel).” 8

In a shiur, he taught: “From the first verse of the Haftorah (of Parashat Pinchas – Melachim 1, 18:46), we learn the value of the Kingship of Israel and our relationship to it. ‘And the hand of Hashem was upon Eliyahu, so he girded his loins and ran before Achav until the approach of Yizre’el.’ Our Sages learned from this: ‘The fear of the Kingship should always be upon you,’ (Zevachim 102A, and Menachot 98A). It is known to us how strained was the relationship between Eliyahu the Prophet and Achav, the king, to the extent that Achav referred to Eliyahu with the term, ‘the troublemaker of Israel,’ (Melachim 1, 18:17), and Eliyahu responded: ‘I have not troubled Israel; but you, and your father’s house,’ (ibid. 18). Nonetheless, the hand of Hashem was on Eliyahu to take him to the king, and Eliyahu arranged his clothes and pants in a manner to enable him to run quickly before Achav, who was worse than Yerovam ben Navat. Ostensibly, Eliyahu should have purposefully disregarded a horrible and dreadful king like Achav and not come to him. From this, we learn a lesson for all generations regarding the respect due to the Kingship of Israel.” 9

Rabbi Yochanan learned about the proper relationship toward Kingship from Eliyahu’s relationship with Achav, about whom it was said: “But there was none like Achav, who gave himself over to perform wickedness in the sight of Hashem, because Izevel, his wife, incited him,” (Melachim 1, 21:25). On the one hand, it is proper to express criticism, even extremely harsh criticism when appropriate, and on the other hand, one must grant honor. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda acted this way toward the political leaders of Medinat Yisrael. He spoke at great length about the issue of giving honor to the Kingship, but he did not refrain from sharply criticizing the Government at the required time, regardless of the political party to which a political leader belonged.

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would object if someone defined him as a “right-winger.” He did not see himself as affiliated with the right or with the left. Political alignment did not have any meaning to him. His world view did not flow from the political situation in the slightest way; rather, they were the Torah’s world view. As a result, he had specific viewpoints relating to the Land of Israel, the Kingship of Israel, and the Government of Israel. According to the Torah’s point of view, he supported certain socialist aims which characterized the leftist perspective. He was not affiliated with any specific party, but saw himself as being above the parties. He nevertheless voted in elections, not out of a party affiliation, but out of the conviction that in the given situation, the act of voting could help the Nation of Israel.

It once happened that a Rabbi said: “We achieved this [particular] religious law with the help of dirty politics.” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda commented: “These politics are the politics of the Master of the Universe.”

David Ben Gurion

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda spoke sharply against David Ben Gurion for boasting that he lived with a woman without having performed the customary Jewish matrimonial procedures of Chuppah and Kiddushin. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda explained that as long as Ben Gurion was the Prime Minister, he did not speak out against him, since he was bound by the Torah obligation to honor the kingship. Only after Ben Gurion left his position did the Rabbi permit himself to say such harsh things.

When HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was asked if one should stand for the siren at the time of the death of Ben Gurion, he responded: “This is connected to the State, and the State is the fulfillment of a positive Torah commandment, therefore one should stand. Even though Ben Gurion was a heretic, he nonetheless has the merit of developing the Negev.”

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would speak out with great force against deficiencies in the State of Israel, but this did not limit his love towards it. When people claimed that Prime Minister Ben Gurion permitted raising pigs in Israel, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda responded: “I don’t want Ben Gurion’s pigs, but I love the State of Israel of which Ben Gurion is the head. 10

When Ben Gurion celebrated his eightieth birthday, every political party sent delegations to Sedei Boker, where he lived in the Negev, to bless him. When Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Shragai visited HaRav Tzvi Yehuda in his Sukkah, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda harshly criticized the Mafdal religious-Zionist political party for also sending a delegation: “As long as he was the Prime Minister, we were obligated to honor him. Now – Baruch Hashem – we are free from him, and we have better Prime Ministers than him.” Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Shragai replied: “HaRav, one should not speak badly about the Nation of Israel in the Sukkah.” But HaRav Tzvi Yehuda repeated his words.

Golda Meir

An important Rabbi spoke with HaRav Tzvi Yehuda about the Prime Minister, Mrs. Golda Meir in a derogatory manner. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was silent and did not answer. But when he departed, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said emotionally: “I cannot speak about the Prime Minister this way; the Prime Minister of Israel is an angel of Hashem to me.”

Dr. Zerach Warhaftig

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda had strong criticism for the Minister of Religious Affairs, Dr. Zerach Warhaftig, z”l, because he did not suspend the heretical lectures of a certain philosopher at Bar Ilan University, and he did not relate to HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s objections during their discussion. When they needed to meet again over a particular matter, Dr. Warhaftig informed HaRav Tzvi Yehuda that he would come to his house. Rabbenu wore his holiday clothing and stood outside out of building with excitement, so that the guest would not have to knock on the door; rather HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would greet him and escort him inside. He said: “All of this is on account of the fact that he is a Minister in the Government of Israel, and it is an obligation to treat him with the honor of the State. Furthermore, my criticism of his actions does not nullify the honor due to him as a Minister of the State.”

Chaim Moshe Shapira

In a similar fashion, he related to the Government Minister Chaim Moshe Shapira, z”l, even though he criticized him strongly over a particular issue. He treated him with honor in all places and at all times, and referred to him as, “Our Interior Minister.”

Michael Chazani

When the Government Minister Michael Chazani came to visit the home of the Rabbi, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda turned on all of the lights, as he did to honor Shabbat. When a student asked why, he responded: “He is a Minister of Israel.”

Moshe Dayan

On the first Yom Yerushalayim after the Six-Day War, the Yeshiva planned a festive gathering and they sent invitations to various Governmental Ministers and important figures. A positive response was received from the popular war hero, Moshe Dayan. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was extremely excited, despite the sharp public criticism he had for Moshe Dayan, and he blessed and praised him. At that gathering, Moshe Dayan delivered a Dvar Torah in the Yeshiva and said that our forefather Yaakov was wounded by the angel, but in the morning the sun shone for him, and he added: “Even when there are those badly wounded in the war, and even when there are casualties in battle – the vision and the hope remain.” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda kissed him and said: “We hope that our Moshele will enter the Government soon.” And it happened. Of course, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda did not agree with all of what Moshe Dayan did, but he greatly valued his military genius, strait-forwardness, and self-sacrifice.

Menachem Begin

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was once in the hospital. He lay on the bed without responding. Students tried to engage him in conversation, but the Rabbi did not answer. An announcement arrived that the Prime Minister, Mr. Menachem Begin, needed to see him. The students felt the time was not appropriate – perhaps HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would be embarrassed because of his condition. When a nurse came to perform a treatment for him, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda awoke and said, “Perhaps later,” because he did not want the Prime Minister to arrive in the middle. He strengthened himself, sat on the bed, and requested a towel. When the Prime Minister arrived, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda became completely alert. Everyone was amazed. Then he requested that he and the Prime Minister be left alone together. At the end of the conversation, Mr. Begin said: “Jerusalem, mountains surround her, and Hashem surrounds His Nation,” (Tehillim, 125:2).

Tzahal – Israel Defense Force

In the eyes of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, the uniform of the Israel Defense Forces was holy. Once at a wedding of a student of the Yeshiva, HaRav Shear Yashuv Kohen, when the groom came dressed in an army uniform there were some learned guests who remarked that it was inappropriate for a groom to stand under the chuppah wearing an army uniform. In Yerushalayim, the Holy City, it was customary that a groom wore Shabbat clothing, holy clothing, like a shtreimel. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda commented: “I will tell you the truth. The holiness of the shtreimel – I do not know if it is one-hundred percent certain. It was made holy after the fact. Many righteous and holy Torah Scholars wore it. They were filled with the awe and reverence of Heaven, and we are like dirt under the soles of their feet. On this account, the shtreimel was made holy. Also Yiddish, the language of the Exile, was made holy because of its prevalent use in Torah study. But from the outset – it is not so certain. In comparison, the holiness of the uniform of an Israeli soldier is a fundamental, essential holiness. It has the unquestionable holiness of being an accessory to a mitzvah (the Torah commandment to conquer the Land of Israel and to keep it under Jewish sovereignty, as clearly defined by the Ramban.) From this perspective, all of the tanks in Tzahal are holy as well.” 11

It once happened that HaRav Tzvi Yehuda sat next to a taxi driver who was wearing a Tzahal uniform, and the Rabbi tapped happily on his leg during the entire trip. The driver turned in surprise to the student who was escorting the Rosh Yeshiva and asked why the Rabbi was so happy. The student responded that this was on account of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s great love of the holy Tzahal uniform.

Once while HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was teaching a class, a student on leave from the army stood next to him. During the entire time, Rabbenu rested his hand on the student’s arm. At the end of the class, another student asked about this. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda explained: “It is simple. He was wearing a Tzahal uniform and I was touching holiness the entire time.” 12

HaRav Tzvi Yehuda’s love of the Israel Defense Force and the holy soldiers of the Army was unique. Not surprisingly, his students who were in the Army endeavored to visit their Rabbi while attired in their army uniform in order to give him contentment. His blessing of students, before their departure to the Army, was pleasand and sweet. It once happened that a student came early in the morning to HaRav Tzvi Yehuda on the day he was drafted into the Army. Hearing a knocking on the door, the student who was helping Rabbenu that day woke up and looked to see who was knocking. He informed the half-sleeping Rabbi that there was a student of the Yeshiva who had come to receive his blessing before his induction into the army. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda got up with incredible zeal. Joyfully, he recited the morning blessings. He quickly drank the cup of tea he allowed himself each morning in order to fulfill the mitzvah of honoring his father who had instructed him to do so. When the young man entered the room, Rabbenu kissed him and blessed him fervently. He encouraged him to be strong in his holy service to the Nation. The elderly Rosh Yeshiva even left his home to escort the student on his way. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said that he must always place before his eyes the verse: “Whoever is among you of all His people, Hashem his G-d be with him, and let him rise up!” (Divrei HaYamim, 2, 36:23) 13

Generally, when blessing a student going off to the army, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would quote the verse: “Serve Hashem, your G-d, and Israel, His Nation,” (Divrei HaYamim 2, 35:3).

A reporter asked HaRav Tzvi Yehuda: “If the honorable Rabbi teaches that the Israel Defense Force is holy, he should close the Yeshiva and not postpone the army service of the students.” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda responded: “The Army is holy; the Torah is holy of holies.”

After the Six-Day War, there was a meeting between government officials and the head of Yeshivot. Representing the government and army was Moshe Dayan, and representing the yeshivot were HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, HaRav Yechezkel Abramsky, and HaRav Chaim Yaakov Goldvicht. When Moshe Dayan asked why Yeshiva students are exempted from the army while other youths fight and die to protect the country, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda responded that he rejects the term “exempt.” His students, he clarified, are not exempt from the army, but rather delay their entry for a few years to solidify their Torah education before going out to defend their country. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda advocated juggling these two imperatives – Torah study and army service – by first strengthening one’s growth in Torah and only then serving in the army. 14

Once, Jews went to pray at the Cave of Machpelah in Hevron and waved the Israeli flag there in defiance of the orders of the Army and the Border Police. An argument broke out between them. One side pulled the flag in one direction, and the other side pulled in the other direction, until it ripped. When the matter was brought to the attention of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda, he said that placing the Army and the Police, who are our friends, in such an incredibly unpleasant situation of having to take the flag away from Jews is more treif than pig.

When Tzahal blew up the nuclear reactor in Iraq in the year 5741, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said in a voice trembling from excitement: “Did you hear! All of the Gentiles are shaking and scared from what the Jews did. Did you hear! Did you hear!” He could not calm down. At that moment, a pregnant woman came in and requested a blessing for an easy pregnancy. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda warmly blessed her, then returned to saying: “Did you hear! Did you hear!” On seeing the Rosh Yeshiva’s concern for the Nation, then for the pregnant women, then back to the Nation, a student remarked, “clal, u-perat, u-clal” – the community, the individual, the community, one of the 13 Talmudic expositions of the Scriptures. 15

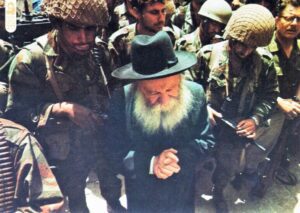

Rabbi Shear Yashuv Kohen, son of the Nazir, and the Chief Rabbi of Haifa, related that during the War of Independence there was a major dispute between Rabbis – including within Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav – whether Yeshiva students should be drafted into the military or continue on with their study. The students followed the advice of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda and the Nazir who encouraged them to learn while active in the Haganah, Etzel and Lechi. During the interim period when there was little fighting, after the UN vote and before the end of the British Mandate, Rabbi Shear Yashuv would learn in the Yeshiva. One day, he saw a street poster with a bold heading which proclaimed that HaRav Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook opposed drafting Yeshiva students into the army, along with harsh quotes from one of his letters regarding this issue. Rabbi Yashuv was unsure what to do, and continued on his way, deep in thought, when he bumped into HaRav Tzvi Yehuda. Noticing his distraught state, the Rosh Yeshiva asked, “Shear Yashuv, what happened? Why are you so upset and pale?” He told him what happened and pointed to the street poster. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda roared: “This is a distortion! This is a total distortion!” over and over. After he calmed down, he explained that these quotes were taken from a letter of Maran HaRav Kook to Rabbi Dr. Hertz, Chief Rabbi of England, regarding Jews being drafted into the British army. Yeshiva students who arrived in London from Russia and Poland as refugees of World War I were excluded from the list of those exempt from military service. In the letter, Maran HaRav Kook made clear that such an exemption had nothing to do with the war for Jerusalem, (“Letters of Rabbi Kook, Vol. 3, Letter #810). Later, Rabbi Shear Yashuv encouraged and aided HaRav Tzvi Yehuda to publish a booklet clarifying this issue. 16

During the difficult battle for the Old City in Jerusalem, the Jewish community was forced to surrender and flee. Rabbi Shear Yashuv was badly wounded in the leg and he was taken into Jordanian captivity with other Jewish prisoners. He thus did not merit seeing the publication of the booklet he initiated. After approximately eight months of imprisonment and the establishment of the State, he was released and taken to Zichron Yaakov for rehabilitation. Within a day, at a time when buses were rare, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda appeared outside his window. He entered the room, hugged and kissed him and burst out crying. He removed a small booklet from his pocket and gave it to him. It was the first booklet printed, dedicated to Rabbi Shear Yashuv. 17

Reading the Newspaper

When HaRav Tzvi Yehuda returned from morning prayers, he would spread out the newspaper HaTzofeh in front of him and say, “Let’s see what the Holy One, Blessed Be He, is doing with us today.”

When a student asked HaRav Tzvi Yehuda if he should read the newspaper, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda responded that he should not. The student said: “But isn’t this the Yeshiva of Clal Yisrael, and don’t we need to know what is happening in the Nation?” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda responded: “When you are a Torah giant of Clal Yisrael ,then you can read the newspaper.”

During a class, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda was furious because of a particular incident in the country, and he saw that a Torah Scholar, who was one of his students, did not understand why. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda asked him: “You do not know what is being discussed?” The student responded: “I do not read newspapers and do not listen to the media.” HaRav Tzvi Yehuda said with discontent and surprise: “Am I the only one who needs to be idle from Torah?”

The Pope

In the year 5723, the Pope was about to arrive in Israel and requested that the Sefardic Chief Rabbi of Israel, HaGaon HaRav Yitzchak Nissim, come to greet him in Megiddo. He refused and said that the Pope should come to him in Jerusalem. Rav Nissim stood firm against all of the pressure against him. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda strongly supported his position. 18

Chapter Four

Eretz Yisrael

When the school “Talmud Torah Morasha” was established, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda instructed the teachers to begin the young students with Parashat Lech Lecha and Avraham Avinu, the father of our Nation, and with his connection with the Land of Israel. 1

Once a new student introduced himself as an “American”. HaRav Tzvi Yehuda pointed out that he was not an American, since America is a foreign land, alien to the soul of Jew. “You should rather say: ‘I am a Jew from the Exile of America.’” 2

During Birchat HaMazon, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would emphasize: “And build Yerushalayim, the holy city, speedily in our days.” 3

After a seudah on weekdays, HaRav Tzvi Yehuda would not recite “Al Naharot Bavel” but rather “Shir HaMa’alot” at each meal, as a result of our having returned to our Land. 4