The Book, Eim HaBanim Semeicha, just as Powerful Today

by Rabbi Moshe D. Lichtman and Tzvi Fishman

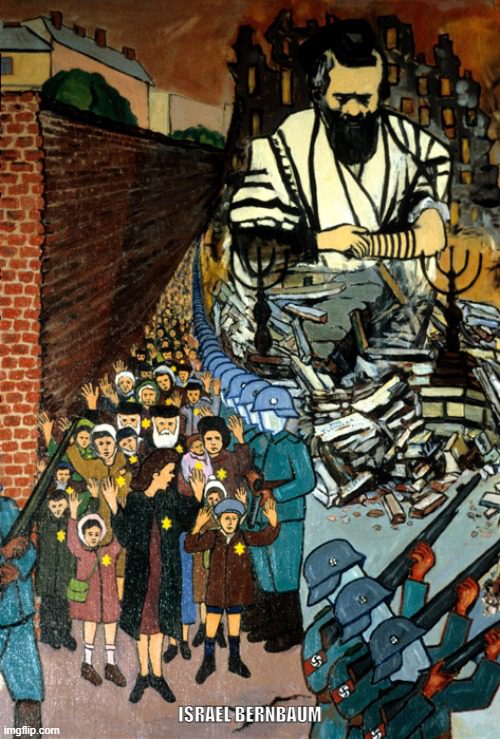

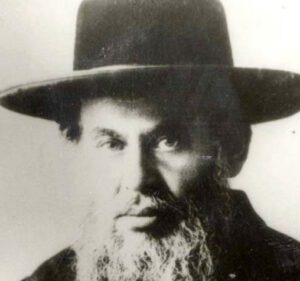

Rabbi Yissachar Shlomo Teichtal, author of the famous book, Eim HaBanim Semeicha, was murdered 76 years ago while being transported in a crowded railway car from Auschwitz to the death camp Mauthhausen. To learn more about his life, I spoke with Rabbi Moshe D. Lichtman, whose skillful translation brought the book alive to English-speaking readers the world over. Rabbi Lichtman, originally from New Jersey, lives in Beit Shemesh, Israel. He is also known for his translation of Simcha Raz’s definitive biography of Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook, An Angel Among Men, and for his Torah commentary, Eretz Yisrael in the Parashah, all available at Amazon Books.

“Rav Teichtal was a renowned Gadol in Europe by the age of 24. In my opinion, if he were alive today, there would be no one close to him in Torah scholarship. He was also a master darshan. I have given many shiurim based on his writings, and the listeners are always spellbound. In his generation, he was on par with the Chofetz Chaim. He knew the entire Torah by heart. Growing up in Hungary, the center of Satmar Jewry, he was influenced by the anti-Zionist opinions of the great Rabbis around him, naturally adopting their negative outlook regarding the Zionist Movement. Until the Holocaust, the issue did not occupy him at all. He filled his time with learning and Halachic writings. In the Introduction to Eim HaBanim Semeichah, he writes: ‘Now that we have encountered unwanted days, my thoughts are preoccupied with the troubles of the generation. I am, therefore, unable to delve into ordinary Halachic matters, as has been my practice since my youth, since such study requires clarity of mind. Moreover, the storms of exile which have assaulted us, have banished the students from my yeshiva. I remained alone, isolated with my thoughts over the present-day destruction of the people and communities of Israel. Why has the Lord done this? What is the meaning of this terrible anger?’ With the increasing persecution of Jews, and with Jewish life in Europe on the brink of destruction, he put his Halachic research aside. Many of his handwritten tomes have never been published. While he was hiding from the Nazis in Budapest, he hid them with a Gentile neighbor. After the war, one of his daughters retrieved them.”

When did he go into hiding?

“Back in 1921, Rav Teichtal became the Av Beit Din and Rabbi of the city of Pishtian in Czechoslovakia, where he headed the Moriah Yeshiva for twenty years. When the Nazis invaded the country in 1938 and began the oppression and deportation of Jews, he escaped across the border to Hungary with his daughters, planning to send for his wife. When she received a report that they had been captured, she sank into a deep depression, believe that they had been killed, like so many others. Hearing that they had been miraculously freed, she waited hour by hour throughout the Pesach holiday for their return. When they arrived, her joy was so great, she was unable to speak. Rav Teichtal writes, ‘The way that this mother felt overwhelmed with anxiety and sadness during the captivity of her children, this is the way that our mother, Tzion – Eretz Yisrael – feels after the nearly 2000 year exile of her children.’ This is why he named his book, Eim HaBanim Semeichah – ‘The Mother of the Children is Joyful’ – meaning Eretz Yisrael is joyous when her children begin to return.”

How do you explain his dramatic turn-around from being a staunch anti-Zionist to an outspoken advocate for mass Aliyah?

“I think that all of his life he simply accepted what he had been taught by his teachers. After his second attempt to reach Hungary succeeded, and he went into hiding in Bucharest as a wanted fugitive, he had time to ponder the question. Although the transportation of Hungary’s Jews didn’t start until the final stage of the war, having crossed the border illegally, he couldn’t walk freely on the streets of the city. Without any books whatsoever, he reviewed the entire Torah with his extraordinary photographic memory and reached the conclusion that, ‘The sole purpose of all the afflictions which smite us in our exile is to arouse us to return to our Holy Land… This is what inspired me to examine the perseverance of the exile and, with God’s help, to author this work. I intend to publicly express my opinion, to teach and advise our people, the Children of Israel, how to hasten the future Redemption, speedily in our days. I have accepted this upon myself as a vow in times of trouble. Since it is prohibited to delay fulfillment of a vow taken in times of distress, and since I have enjoyed some respite ever since arriving to the capital, I have begun to write a volume on the rebuilding of our Holy Land.’ He mentions fifteen times in the course of the book that he doesn’t have any books to substantiate his sources, then goes on the quote the source exactly, or almost exactly; not only the texts from the Torah, Tanach, or Gemara, Rishonim, and Achronim, but all the commentaries on them as well. He writes: ‘The purpose of this work is to raise our Land from the dust and stimulate love and affection for it in the hearts of our Jewish brethren, young and old alike, so that they may yearn and strive to return to our Land, the Land of our forefathers, and leave the lands of exile… The essential point is that HaShem is waiting for us to take the initiative, to desire and long for the return to Eretz Yisrael. He does not want us to wait for Him to bring us there. Therefore, He told us, ‘And I will truly implant them in this Land.’ That is to say, when we, on our own volition, truly and with all of our strength, desire and strive to return to the Land, then God will complete the work for us beneficially.’”

How was the book received upon publication?

‘We really don’t know. Writing almost non-stop, the book took him a little over a year to complete. He managed to bring it to a printer himself in Bucharest in 1943. Because of his fugitive status, in order not to be recognized, he trimmed his beard drastically and dressed like a laborer. Needless to say, when the Nazis sent the Hungarian Jews to the death camps, many records were lost. From his own writings, we know that Rav Teichtal would venture out to secret meetings of Jews to give sermons about his great revelation, and to urge them to find ways to escape the coming doom. With a heavy heart, he bemoans the fact that when he requested to speak at these underground meetings and prayer gatherings, when synagogues had been closed, he was told not to talk about Eretz Yisrael. In a tone of anguish, he notes that Rabbis maintained that the Angel of Death had been given permission to destroy the Jews of Poland because of those who supported the Zionist enterprise. From what he writes in the book’s introduction, we can assume that few people heeded his impassioned warning and call: ‘Those who have a predisposition on this matter will not see the truth and will not concede to our words. All the evidence in the world will not affect them, for they are smitten with blindness and their inner biases cause them to deny even things which are as clear as day. Who amongst us is greater than the Spies? The Torah testifies that they were proper individuals. Nonetheless, since they were influenced by their desire for authority, and thus, they rejected the desirable Land and led others astray, causing this bitter exile, as Chazal explain… The same holds true in our times, even among Rabbis, Rebbes, and Chassidim. This one has a good rabbinical position; this one is an established Admor, and this one has a profitable business or factory, or a prestigious position which provides great satisfaction. They are afraid that their status will decline if they go to Eretz Yisrael. People of this sort are influenced by their deep-rooted selfish motives to such an extent that they themselves do not realize that their prejudice speaks on their behalf.’ Another possibility is something I heard from the Gadol, Rav Zalman Nechemiah, of blessed memory. When I finished the English translation, one of Rav Teichtal’s sons, Menachem, who lived in the Old City of Jerusalem, took me Rav Nechemiah to request an approbation for the book. He said that the author’s urgent call for aliyah perplexed him, since, by the time the book appeared, the Jews were trapped with no way to flee. I humbly replied that from my very concentrated work on the translation, it seemed to me that Rav Teichtal knew that immediate escape was no longer an option. He was writing for the day after the war, to the Jews who survived – what would they understand from the inexpressible horror? He wanted them to know that there was no future for the Jewish People in the Diaspora among foreign nations, and that the time had come to return home to the Promised Land, without waiting for Mashiach to bring the Redemption about miraculously, but rather it depended on the Jews themselves, through their own efforts and actions. Thus, for example, he writes: ‘The Or HaChaim states that Israel’s leaders throughout the generations will be held responsible for the fact that we are still in exile, because they should have inspired the Jews to love Eretz Yisrael. The leaders of the generation must inspire the Jewish People to help bring the Redemption closer by using the natural means that G-d has prepared for us. We are not worthy enough for it to occur with manifest miracles, rather only with miracles disguised in seemingly natural events, as in the days of Cyrus… I know that the humble ones who separate themselves from the building effort do so for the sake of Heaven. They fear that they and their children may be harmed by joining people whose ways have strayed from the path of the Torah. Behold, we can say about such people that although their intentions are acceptable, their actions are not, for many reasons. All Jews must be united in order to fulfill the positive commandment of the Torah of building and settling the Land. This cannot be accomplished individually. Therefore, do as you are commanded! Further, no harm will come to a Jew who participates in this great and exceedingly lofty mitzvah. On the contrary, if a large number of Orthodox Jews join in, they will enhance the sanctity of the Land, as I previously cited in the name of the holy Rebbe of Gur and the Ramban. Since we are commanded to build the Land and raise it from the dust, it is forbidden to be overly pious and undermine this endeavor, G-d forbid. Rather, we must build with whomever it may be and concentrate on enhancing the sanctity of the Land. Then Hashem will assist us.’”

I heard that when the original Hebrew version of book was published in Israel in 1983, not all of the Teichtal family agreed.

“I understand from the publisher, Rabbi Danny Cohen, that there was a family dispute on ideological lines. One of the Rabbi’s sons belonged to the Lubavitch community in New York, and he didn’t want the book to be published in Israel. After the Holocaust, the book was published in Hebrew in America in a limited edition, which, I have heard, was bought out almost in its entirety by some religious group opposed to Zionism, which proceeded to burn all of the copies, but I cannot vouch for the accuracy of that report. In any event, one of the sons living in Israel, Menachem, the one who brought me to meet Rav Zalman Nechemiah, who felt less antagonistic toward Medinat Yisrael, and who eventually gave his permission, asked the Rebbe of Chabad what to do. The Rebbe replied that Rav Teichtal was a Tzaddik, not a ‘Zionist’ in the pejorative use of the term, and that the book was a legitimate Torah study about Eretz Yisrael. So the son gave his permission on the condition that a letter from him would be included at the beginning of the book, explaining that his father was not a Zionist, but rather wrote the treatise out of his great love for the Holy Land.”

How did Rav Teichtal die?

“When the Final Solution of the Nazis finally reached Hungary, Rav Teichtal tried to flee with his family back to Czechoslovakia, hoping the situation was better there. They were captured and sent to Auschwitz toward the end of the war. Then, as the Russian armies drew close to the extermination camp, the Nazis transported the inmates deeper into Germany. During the train ride to Mauthausen, the guards threw crusty chunks of bread to their captives. When a Ukrainian prisoner grabbed a piece out of the hand of an old and starving Jew, Rav Teichtal protested. Others Jews warned him to mind his own business, but he demanded that the thief return the bread. A student, who was in the cattle car as well, says that Ukrainian prisoners and a Nazi guard beat Rabbi Teichtal to death.”

Do you have any indication how readers of the English translation have reacted to the book?

“Baruch Hashem! The response has been fantastic. Of course, I haven’t heard from everyone, but I have received many letters of thanks, including testimonials from people who made Aliyah after having read the book. For one thing, Rav Teichtal’s style is amazing in its combination of passion, Torah erudition, and unrelenting truth. His Torah greatness and honesty jump out from the pages. He can disagree with the opinions of other Rabbis because his understanding of Torah comes across as much more encompassing than theirs, and because he doesn’t let any extraneous factors or considerations of self-interest affect his views. I am certain that thousands of people have been inspired and awakened by the clearly-presented discussions and scholarly proofs in the book which emphasize the vitalness and centrality of Jewish Life in the Land of Israel. In my opinion, with the world upheaval that Corona has caused, and with ever-increasing anti-Semitism, the message of the book is just as real today. After reading Eim HaBanim Semeicha, you cannot return to being the same person unless your head is filled with denial and the need to guard yourself from the truth.