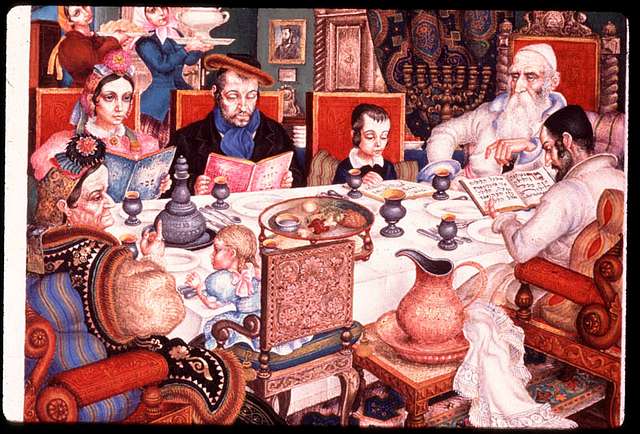

Chapter 31 – The Seder

From the book “Jewish Tradition” by HaRav Eliezer Melamed, the Rabbi of Har Bracha and author of the series “Peninei Halacha.”

- Introduction to the Seder

The Exodus from Egypt is so fundamental to Jewish faith that we mention it in every Shabbat and Yom Tov prayer service and Kiddush. Actually, the mitzva to mention the Exodus applies every day and every night, as we read (Deuteronomy 16:3), “so that you remember the day of your departure from the land of Egypt all the days of your life.” (The night obligation is derived from the extra word “all.”) Usually, we fulfill the mitzva when we read the third paragraph of the Shema, which mentions the Exodus (22:4 above).

However, we do not make do with a simple mention at the Seder (which takes place in Israel on the first night of Passover and in the diaspora on the first two nights). Rather, there is a special mitzva then to retell the story of the Exodus at length. This is meant to provide a solid foundation for the faith and mission of the Jewish people, so the light of that faith can illuminate the entire year.

We have two primary goals at the Seder: to tell the story of the Exodus for our own sake, and to pass this story on to our children. With these goals in mind, on this holy night every one of us must view himself as if he personally went out of Egypt. We must tell the miraculous story at length, eat the matza and maror which illustrate the miraculous story, enjoy a festive meal, and conclude with praise of God. In Temple times, there was also a mitzva to eat the Paschal offering, which expressed the uniqueness of the Jewish people (30:1 above).

As a rule, everyone at the Seder has a copy of the Haggada, the guidebook to the Seder. Its largest section is called Maggid, which tells the story of the Exodus. (The literal translation of both Haggada and Maggid is “telling.”) Typically, the text is recited out loud. However, it is praiseworthy to go beyond the text and expand upon the story of the Exodus, the mission of the Jewish people, and God’s kindness to us. When there are children at the Seder, the adults should focus on explaining the story in a clear and simple way appropriate to children, so as not to lose their attention.

Some families have a beautiful custom at the Seder in which older relatives tell their personal and family stories, passing them on to the younger generation. These stories focus on how the family remained connected to Jewish tradition, and (when relevant) how they participated in the Jewish people’s modern exodus and came to live in the Land of Israel, and take part in settling it.

- Starting the Seder with Questions

There is a special value in conveying the story of the Exodus in question-answer format. Posing questions opens the mind and heart to receiving answers. Since the message we need to convey at the Seder is foundational, we are commanded to transmit it in the best way possible.

For the same reason, we are commanded to eat matza and maror (as well as the Paschal offering, when there is a Temple). Having these unusual foods at the Seder makes it clear to the children that this night is unique and piques their interest, which leads them to ask about its significance. To encourage children’s questions, the Sages instituted doing a number of things at the Seder in unusual ways.

This is also why the Sages formulated Ma Nishtana (the Four Questions) at the beginning of Maggid, in which the children express their surprise at our unusual Seder behavior. Their asking these questions prompts the adults to answer by telling them about the Exodus. If no children are present, an adult recites Ma Nishtana. Even an individual who is alone at the Seder must begin with the questions of Ma Nishtana.

- The Four Children

The mitzva to retell the Exodus story to children appears four times in the Torah, and it is formulated differently each time. This implies that the story must be presented in a style appropriate to each child, in accordance with their understanding and character. A smart child should be given a deep, detailed answer. A child who is rebelling against tradition (in the manner of the wicked) should be encouraged with messages of faith, in hopes that these words will penetrate his heart. A simple child should be wowed with stories of the great miracles God performed for us. Even if a child is apathetic and cannot be bothered to ask questions, his interest might still be piqued by the special Seder foods which illustrate the story.

- Themes of Maggid

Maggid tells the Exodus story by starting with the negative and moving on to the positive. That is, we were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, after which God redeemed us. Additionally, our ancestors (such as Terach and Laban) started out as idol worshipers. Only through a long process of refinement did we become a nation of monotheists. At first, it might seem better to tell only nice, uplifting stories. In fact, the more we contemplate the tragedy of being slaves and the shame of our ancestors’ idol worship, the more we appreciate the magnitude of the redemption. The contrast is comforting and encouraging as well, because it teaches us that growth and redemption can spring from suffering and failure.

Someone who cannot recite all of Maggid should minimally recite the parts that explain the significance of eating the Paschal offering, matza, and maror, as these express the most essential ideas of the Seder. In short, the Paschal offering represents the uniqueness of the Jewish people; the matza represents faith and freedom; and the maror represents the enslavement, which purified and prepared our hearts for faith and Torah.

The ten plagues are another subject addressed in Maggid. The Torah provides an extensive description of the ten plagues in order to teach us that there is a Judge who metes out justice in this world, and that eventually the wicked are punished. People as evil as the Egyptians – who brutally enslaved an entire nation and cruelly drowned their children – deserve to be punished accordingly. This lesson will stand for all time.

- Seder Preparations

The table should be set beautifully for the Seder. Comfortable chairs which are suitable for reclining should be placed around the table, and beautiful dishes should be used, reflecting the joyous nature of the Seder. Nuts and candy should be available to distribute to the children at the beginning and throughout the Seder, to keep them happy and encourage them to ask questions and stay involved. It is customary to wear new clothing at the Seder, or at least one’s most festive clothing.

Before Seder, a Seder plate is prepared with the ritual foods of the Seder, each one of which expresses a particular idea:

- Three matzot remind us of faith and freedom.

- Maror (lettuce or horseradish) reminds us of the enslavement.

- A roasted shank bone (an animal bone, or more conveniently, a chicken wing) commemorates the Paschal offering.

- An egg (cooked or roasted) commemorates the festive Ĥagiga offering and reminds us that one day the Temple will be rebuilt.

- Karpas (a vegetable) is eaten at the beginning of the Seder to whet the appetite.

- Vinegar or salt water, into which the karpas is dipped.

- Ĥaroset (a fruit spread made of some combination of apples, dates, nuts, and more) commemorates the mortar which our ancestors made in Egypt. The maror is dipped in ĥaroset before being eaten.

It is proper to set the table and have the Seder plate ready before the festival begins, so that when people get home from synagogue following the Ma’ariv service, the Seder can be started immediately with Kiddush. (It is important to avoid delays, because they decrease the precious time when the younger children will still be awake and alert.)

- The Four Cups

The Sages instituted drinking four cups of wine at the Seder in order to increase the celebration of our redemption and to give expression to our freedom. The four cups are integrated into the Seder as follows. Kiddush, which contains some of the essential ideas of Passover, is recited over the first cup. Maggid, including the story of the Exodus and the first part of Hallel, concludes with the second cup. Birkat Ha-mazon is recited over the third cup. Finally, we recite the second part of Hallel (along with other praises of God) over the fourth cup. Thus, each of these four stages is accompanied by wine.

The Sages explain that the four cups correspond to the four expressions of redemption used by the Torah (Exodus 6:6-7). As a rule, the number four represents completeness, as it corresponds to the four cardinal directions of the world. Since the Exodus brought about a complete upheaval of the world, we drink four cups of wine in its honor. Many people think that holiness can be expressed only in spiritual activities like prayer and Torah study. They think that the more ascetic a person becomes, the greater holiness he will achieve. To combat this error, the Sages instituted the recital of Kiddush over wine on every Shabbat and festival. In addition, they incorporated four cups of wine into the Seder. This teaches us that complete holiness is manifested when we integrate Torah and faith with physical celebration and joy, giving the body its due.

It is preferable to use a fine wine for the four cups, one that not only brings cheer but also can be savored. The wine should be alcoholic, as this induces feelings of happiness, release, and freedom. At the same time, people should not drink so much that they become tired or drunk. Therefore, some have a custom to water down the wine or use a relatively small cup, so that they remain happy and lively through the recitation of the Haggada. Those who find drinking wine unpleasant (for example, it gives them a headache) may fulfill the mitzva with grape juice instead.

The wine glass must contain at least a revi’it of wine (about 75 ml or 2.5 oz.). Generally, a wine glass is larger than this. To honor the mitzva, the glass should be filled up, but not so full that it will spill. While drinking all of the wine is preferable, it is sufficient to drink the majority of a revi’it (about 40 ml).

Reclining is required while drinking the wine, as we will explain in the next section. It is preferable to drink the majority of the wine at one time, without drawing it out or talking unnecessarily. However, even if someone ended up taking six or seven minutes to drink the wine, the obligation has still been fulfilled. Children over the age of five or six should be given four cups to drink, but they should be given grape juice rather than wine.

- Reclining

There is a rabbinic requirement to recline when we eat matza and drink wine at the Seder, as part of acting as if we have just been freed from Egyptian bondage. How does reclining express freedom? Someone who is on call sits up straight, so that he will be able to spring into action when summoned to fulfill his duty. In contrast, someone who has been freed from all obligations can casually lean back, allowing all of his muscles to relax.

There was a time when people normally sat on pillows placed on the ground, which meant that sitting up straight indeed required effort. In such circumstances, reclining – the position between sitting and lying down, in which the entire body stretches out on a couch or pillows – was very comfortable and demonstrated a sense of freedom. Today, though, when we normally sit on chairs, reclining at the Seder involves sliding one’s bottom forward to the middle of the seat, leaning back against the chair back, and tilting left. (Ideally, the chair should be comfortable and have armrests.) Why recline to the left? First, it is easier to eat this way, as it frees up the right hand, which most people use to eat with. Additionally, in the past some people were concerned that reclining to the right might cause food to go down the trachea instead of the esophagus, which could lead to choking.

The requirement of reclining applies when fulfilling the mitzva of eating matza, and while drinking the four cups of wine. It is commendable to recline during the rest of the meal as well, if this is comfortable. Reclining is not done while eating the maror, because maror represents slavery. One should not recline during Birkat Ha-mazon, as it must be recited with awe and reverence. Likewise, it is customary to refrain from reclining while reading Maggid, to make it easier to concentrate on it fully and treat it with the seriousness which it deserves.

- Karpas and Handwashing

After the recitation of Kiddush over the first cup of wine and before Ma Nishtana, we eat a little bit of karpas. This is a vegetable which we dip in salt water or vinegar for flavor. In this we are acting like free people, who eat hors d’oeuvres which allow them to patiently wait for the rest of the meal. Eating karpas also leads children to ask why this night is special and so different from all other nights. Some use celery or parsley for karpas, while others use potatoes.

Before eating karpas, we use a cup to wash our hands ritually (as in 23:6 above) but without reciting a blessing. This is because in Temple times, when the laws of purity were in effect, ritual handwashing was required before eating a fruit or vegetable that had been dipped in a liquid. Today, without the Temple, this practice has almost completely ceased. Nevertheless, it is customary at the Seder to follow the practice as if we were in Temple times. (The blessing is not recited because this handwashing is not obligatory.) In practice, then, we ritually wash our hands twice at the Seder – once before eating karpas and again before eating matza.

Someone who wishes to drink water or coffee after the first cup of wine may do so. However, eating is not permitted (apart from karpas), as we want everyone to have a healthy appetite for the matza and the rest of the meal. Someone who is very hungry may eat a little. But all eating and drinking must stop once the reading of Maggid has started.

- Breaking the Middle Matza and Hiding the Afikoman

As we mentioned above (section 5), the Seder leader has three matzot in front of him. The top and bottom ones remain whole, and will later be used for the mitzva of eating matza (section 11 below). The middle matza is broken in two. Why?

The Torah calls matza the bread of poverty (Deuteronomy 16:3). Therefore, it is appropriate to use a broken piece of matza since the poor can only afford broken bits of food. The matza is broken right before Maggid so that all the participants can see the brokenness while reciting Maggid, a tale of poverty and enslavement.

The larger of the two broken pieces is set aside to be used as the afikoman. It will be eaten at the end of the meal in commemoration of the Paschal offering (section 14 below).

In many families, it is customary for the Seder leader to hide the afikoman and for the children to search for it. The child who finds the afikoman returns it at the end of the meal in exchange for the promise of a gift. This custom helps children stay awake for the whole Seder. Some adults promise a gift to every child who stays up until the afikoman is eaten, independent of the hiding and finding.

- Maggid

The second cup of wine is poured before Maggid so that this entire section of the Haggada will be read over wine. (However, for small children it is better to pour the grape juice closer to the time of drinking it, to avoid spillage.)

The matzot are left uncovered during most of Maggid. However, they should be covered each time the cup of wine is raised. (This includes the recitation of Ve-hi She-amda and Lefikhakh, and the blessing about redemption before drinking the second cup.) When reciting the paragraph that explains the significance of eating matza, the Seder leader lifts the matza and shows it to everyone. The same procedure is followed with the maror when reciting the paragraph that explains its significance.

In many families, everyone recites Maggid together. It is also fine for the Seder leader or someone else to read out loud for everyone. The Seder leader sets the pace and decides how long to spend on explanatory material.

When the discussion of the Exodus has concluded and the first half of Hallel has been recited, we conclude Maggid with a blessing of redemption, and drink the second cup. After that, we eat the matza.

- Eating Matza

Before eating the matza, everyone washes their hands and recites the handwashing blessing (23:6 above). The Seder leader then raises the matzot and recites two blessings. The first is “Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, Who has sanctified us with His mitzvot and commanded us about eating matza.” The second blessing is Ha-motzi. (This parallels the Ha-motzi that is recited over bread at every meal on Shabbat and festivals, as we saw above in 26:22.) The leader then passes matza to the other participants.

While eating the matza, everyone should recline (section 7 above). They should intend to fulfill the Torah requirement of eating matza. They should also keep in mind that the matza reminds us of the matza that our ancestors ate when leaving Egypt.

To fulfill the biblical mitzva of eating matza, one must eat a ke-zayit (the volume of an olive) of shmura matza. There is some disagreement as to exactly how much this translates into, but it is fairly standard to follow the calculation of half the volume of an egg (25 ml.). This is about a third of a machine matza (or the equivalent size of a handmade matza). It should be eaten without pausing, and taking no more than seven minutes. (The meticulous eat the volume of two olives, which is about two thirds of a machine matza.)

Afterwards, there is a rabbinic requirement to eat an additional ke-zayit of matza as part of korekh (section 12), and yet another ke-zayit at the end of the meal for the afikoman (section 14). In total, fulfilling all three of the mitzvot of matza requires one machine matza. (The meticulous, who double the amount for the biblical mitzva of matza, end up eating one and a third machine matzot.)

The matza and maror should be eaten by midnight. Ideally, the afikoman should be eaten by then as well.

- Eating Maror and Korekh

Maror is a bitter vegetable eaten at the Seder to commemorate the bitterness of enslavement. There are two vegetables that may be used for maror: lettuce (usually Romaine) and horseradish. Even though lettuce is less bitter, it is the preferred option because it reminds us of the enslavement: just as lettuce starts out soft and tasty but becomes increasingly bitter, so too the time of the Israelites in Egypt started out positively but became increasingly bitter. This is also what happens when a person becomes enslaved to his physical desires. At first, he finds pleasure in satisfying them; but if he continues to do so, he becomes addicted and enslaved to his desires, and his life becomes bitter.

The maror is dipped in ĥaroset (section 5 above) to mitigate its bitterness. However, using large amounts of ĥaroset would defeat the point of eating maror. We recite the blessing: “Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, Who has sanctified us with His mitzvot and commanded us about eating maror.” We then eat a ke-zayit of maror. We do not recline while eating maror, since it commemorates slavery rather than freedom.

During Temple times, Hillel the Elder maintained that there was a biblical mitzva to eat the Paschal lamb together with matza and maror. To commemorate this, after we eat the maror on its own, we put together a matza sandwich (korekh) consisting of a ke–zayit of maror and a ke–zayit of matza, and dip either the maror or the entire sandwich in ĥaroset. (Since we may not offer sacrifices without the Temple, there is no meat in the sandwich.) We then recite the paragraph that starts “Zekher le-mikdash ke-Hillel,” and eat the sandwich while reclining.

- The Meal

After korekh we proceed with the meal. The food should be of high quality, served on fancy dishes. It is permissible to drink wine during the meal. (This drinking is not counted towards the obligatory four cups.) However, eating and drinking should be done in moderation, both so that everyone will have room for the afikoman at the end of the meal, and so that they will have the energy to continue reciting Hallel and the other songs at the end of the Seder.

Many people do not eat roasted meat or chicken at the Seder, in order to highlight the absence of the roasted Paschal offering which was eaten roasted. Others, including Yemenites and some Sephardim, do eat roasted meat at the meal.

- Eating the Afikoman

At the end of the meal, we eat the afikoman. “Afikoman” was a Greek word referring to the sweet dessert at the end of a meal. During Temple times, the meal would conclude instead with the meat of the Paschal offering. Even though it was not sweet, people loved the mitzva so much that they referred to it as the afikoman. After eating the Paschal offering, people would not eat anything else, so that the taste from the mitzva would remain in their mouths for the rest of the night.

Following the destruction of the Temple, the Sages instituted concluding the meal with matza to commemorate the Paschal offering. This is what we call the afikoman today. It should be eaten when people are already full from the meal, but not so full that they cannot enjoy eating it.

Each person should eat a third of a machine shmura matza to fulfill the obligation of afikoman. The matza that was broken and hidden earlier (section 9) should be used for this. However, since it will generally not provide enough matza for all the participants, the Seder leader takes additional shmura matza and gives each person a third of a matza. If the hidden matza has not been found, any shmura matza may be used instead.

After the meal concludes with the eating of the afikoman, there are still two more cups of wine to drink. People may not drink any additional wine or alcoholic beverage, as that might make it look like they think that more than four cups are required. However, water may be drunk freely. Those who want to drink coffee to keep themselves awake so that they will be able to continue talking about the laws of Passover and the story of the Exodus may do so.

- The Seder’s Conclusion

After eating the afikoman, we pour the third cup and recite Birkat Ha-mazon (23:8-9 above) while holding it. Right after Birkat Ha-mazon, we drink the third cup and pour the fourth cup.

After pouring the fourth cup, it is customary to pour an additional cup as well, which is called Elijah’s cup. We do not drink this cup. Rather, when everyone is about to go to sleep, it is covered. The next day, many use this wine for Kiddush at lunch. What is the rationale behind the custom of Elijah’s cup? As explained above (section 6), the Sages mandated drinking four cups of wine, corresponding to the four expressions of redemption used in the Torah’s account of the Exodus. However, there is a fifth expression that describes entering the Land of Israel (Exodus 6:8). The question arises: Is it appropriate for us nowadays to drink this fifth cup? On the one hand, God has blessed us with the State of Israel; on the other hand, the Temple has not yet been rebuilt. As a compromise, we pour a fifth cup, but do not drink it. When Elijah arrives, we will know that the final redemption is truly at hand. From then on, we will drink the fifth cup at the Seder.

While holding the fourth cup, we read the second part of Hallel as well as “the Great Hallel” (Psalms 136) and other praises of God. Then we drink the fourth cup and recite the after-blessing. The Seder traditionally concludes with a number of lively songs about God, the Torah, and the Jewish people.

After the Seder is over, some people read Song of Songs, as it is an allegory for the love between God and the Jewish people. The love between husband and wife draws upon this supernal love.

On Seder night, there is a mitzva to continue telling the story of the Exodus (and expound upon the miracles and wonders which God performed for our ancestors, as well as to study the laws pertaining to the festival, until we start to doze off. In the words of the Haggada, “Whoever discusses the Exodus at length is praiseworthy.”