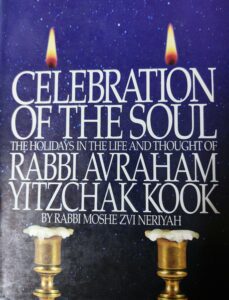

From the book, “Celebration of the Soul” by HaRav Moshe Tzvi Neriyah. Translated into English by Rabbi Pesach Yaffe.

The 28th of Iyar

The 28th of Iyar, the Hebrew date of the unification of Jerusalem in 5727 (1967), was a festive day in Jaffa in 5664 (1904). On that day, the new rabbi of Jaffa, HaRav Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook, first set foot in Eretz Yisrael. Ten years later, on 29 Iyar, the Rav wrote to his son:

“Thank God, yesterday was the 28th of Iyar, the great day on which the Rock of Israel, blessed be He, favored us to come to His pleasant Land and see with our eyes the beginning of the flourishing of His redemption of His holy people”

(Letters II, p. 292).

Thirst for Eretz Yisrael and Jerusalem

Rabbi Yechiel Michel Tukaczinski recounted the Rav’s first visit to Jerusalem: “When we arrived at the home of Rabbi Eliyahu David Rabinowitz-Teomim [the Rav’s first father-in-law], the Rav celebrated with everyone by sharing some original Torah insights, primarily about the sanctity of Jerusalem. After the reception, he climbed up to the roof to be alone. When I returned the next day to Rabbi Eliyahu David’s home, Rabbi David Shatler whispered to me that he feared for the Rav’s health. The latter had been pacing for many hours on the roof, pouring out his soul to God, his eyes toward heaven, as if he were no longer in his right mind. When I mentioned this to Rabbi Eliyahu David, he replied, ‘A great soul dwells within him and it is terribly thirsty for Eretz Yisrael and Jerusalem!’”

“Jerusalem is Surrounded by Mountains ״

When the Rav was stranded in Switzerland during World War I, the unhappy news he received about the situation in Eretz Yisrael in general and Jerusalem in particular greatly disturbed him. Rabbi Shlomo Pines of Zurich, hoping to distract him from his worries, persuaded the Rav to join him on a tour of the snow-covered Alps. Rabbi Pines rented a wagon and they rode out into the mountains toward the most magnificent and breathtaking sites. As they were walking, the Rav was deep in thought, his eyes downcast, paying no attention to the surroundings. Rabbi Pines said to him, “Raise your eyes and see how splendid these mountains are.” “Yes,” said the Rav, speaking as if in a dream, “Jerusalem is surrounded by mountains.”

Jerusalem: Gateway of Heaven

A fundamental principle of the Torah is that all sacred matters are greatly elevated in the Holy Land. Their value increases significantly, well beyond their worth in other lands. Even regarding the Torah, our Sages said of the verse, “The gold of that Land is good” (Gen. 2:12) — “This teaches that there is no Torah like the Torah of Eretz Yisrael and no wisdom like the wisdom of Eretz Yisrael” (Gen. Rabbah 15:7).

Similarly, it is well known that the elevation of all prayers is bound to the supernal quality of the sanctity of our Holy Land and the Holy City of Jerusalem, the dwelling place of holiness and the gateway of heaven, whose supreme spiritual stature was made known to us by our hallowed ancestors, the prophets and divinely-inspired seers. As King Solomon said at the inauguration of the Temple: “And they shall pray to You by way of their Land which You have given to their forefathers, the city which You have chosen and the House which I have built for Your name” (I Kings 8:48).

Because all of the prayers focus upon the Holy Land and the Holy City, the city which is our life-home and the precious locale of our Temple, the supernal idealism of prayer surely reveals itself in this sacred site to a greater extent than it can in other places. The quality of every prayer attains its highest and most sacred value in the place of our sacred Temple, such that its sanctity elevates the inner value of every prayer which is spoken (Ma’amarei HaRe’iyah, pp. 302-3).

Service of the Heart

Rabbi Kook wrote: It is nearly impossible to experience the true taste of Divine worship so long as one has not studied and taught himself the virtue of the human soul, of Israel, of the Holy Land, and the proper yearnings of every Jew for the building of the Temple and the greatness of Israel and its elevation in the world. Our Sages interpreted the verse “And serve Him with all your heart” (Deut. 11:13) as “Service of the heart is prayer” (Sifre). Prayer cannot constitute service unless it emerges from a mental state so permeated with fear of God that the matters of prayer are close to the heart…. If one does not recognize the virtue of Israel, how can he pray wholeheartedly for its Redemption? Obviously, the intention accompanying the blessing “Redeemer of Israel” should not focus upon the private pains felt by each person due to the yoke of the exile; rather, the content of the blessing indicates that it is voiced in praise of the entire Congregation of Israel and its holiness. So, too, if one fails to recognize the virtue of the Holy Land, its qualities and sanctity, how can he pray for the rebuilding of Jerusalem? For prayer must flow from the walls of the heart (Berachot 10b) when one feels that something is lacking (Musar Avicha, pp. 19-20).

In Honor of Jerusalem

Once while the Rav still lived in Russia, a poor Gentile woman arrived in Boisk claiming to be from Jerusalem. But people did not believe her and treated her as an ordinary beggar. When she came to the Rav’s home, his younger brother opened the door. He announced her arrival to the Rav and expressed his doubts concerning her story that she came from Jerusalem. The Rav said, “Even if her integrity is questionable, the very fact that she identifies herself with Jerusalem entitles her to a more generous donation.”

The Banner of Jerusalem

The exultation which greeted the Balfour Declaration planted the idea in the Rav’s mind to enlist the participation of the religious communities in the great project of building the Land. Dissatisfied with the existing (secular Zionist) frameworks, he conceived the founding of a powerful new movement, broad-based and far-reaching, that would encompass the entire Jewish people and even make inroads among the best of the Gentiles. He decided to call it “The Banner of Jerusalem,” a federation dedicated to “the renewal of the sanctity of the sacred Jewish Nation upon the sacred Land.” Its objective would be threefold:

1) To unite all religious Jews to establish a large, central yeshiva in Jerusalem whose students would become leading scholars, teachers, and Rabbis; 2) To establish a nationally recognized rabbinic authority; 3) To publish newspapers, periodicals, and scholarly works that would disseminate the movement’s ideals.

In an open letter issued in Jerusalem in 1921, the Rav wrote the following:

Every sensitive heart must agree that a mighty and beneficial power is latent even in our secular renewal, which calls itself Zion, whose objective is to establish a Jewish State in the Land of our forefathers. But we have seen that, despite the success it has achieved, the secular is not liable to attain its goal as long as the light of holiness does not appear in an exalted manner and illuminate its darkness. This light of holiness grows out of our recognition of the holy, out of the inner, divine yearning in the soul of Israel, out of the light of Israel and its holiness, which is the light of the world and its fullness.

The final objective of the holy is not merely the Jewish State, but the throne of God in Jerusalem: “A glorious throne exalted from the beginning is the place of our Temple” (Jer. 17:12). When we sat beside the rivers of Babylon and wept as we recalled Zion, when our heart was broken and our spirit depressed over our political destruction, we swore immediately, not only for the sake of Zion [in a secular sense], but we directed ourselves toward Jerusalem, “If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember you, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth, if I do not set Jerusalem above my highest joy” (Ps. 137:5). The voice which accompanies us with its pleasant hope twice a year, on the first night of Pesach and in the concluding prayer of Yom Kippur, is the voice of the soul of the nation expressing its deepest desire: “Next year in Jerusalem….”

The time has come to clarify matters. The secular and the sacred in our national life are not contradictory elements. On the contrary, they are mutually constructive, mutually protective, and complementary. Unfortunately, we are still too inarticulate and too feeble to express all of the might of the sacred aspect of the national renewal. But we are certain that clarity of thought and of articulation will surely come as the movement develops. Now we must raise our national renewal out of its secular depths and up to a sacred movement, elevating its value in our inner world and in the larger world of all humanity. The greatest minds in the secular realm were, and are, engaged in our secular renewal. But now the Nation must produce from its midst geniuses of the holy who will engage in our sacred renewal. This is the primary objective of “The Banner of Jerusalem.”

“Jerusalem” is an idea, not a group or an organization in the ordinary sense. We state that the secular cannot be established without a foundation which is sacred, just as the sacred cannot survive without a foundation which is secular. We demand from all our brethren who feel any propensity toward the sacred — and truly they are all the children of our sacred Nation — to recognize their obligation and to publicly declare that as long as we leave our movement of renewal to stand solely on its secular foundation, we endanger its very status, we close the door before its development, and we decrease its honor (Maamarei HaRe’iyah, pp. 338-40).

Zion and Jerusalem

The Rav once explained the symbolic difference between Zion and Jerusalem in the following manner: Isaiah, the prophet of consolation, said: “Herald of Zion, go up on a high mountain; lift up with strength your voice, herald of Jerusalem, lift up, be not afraid, say to the cities of Judah, ‘Behold your God’” (Is. 40:9). Why did the prophet tell the herald of Zion to “go up on a high mountain” while the herald of Jerusalem was told to “lift up with strength your voice”?

Zion symbolizes Jewish sovereignty, while Jerusalem symbolizes Jewish sanctity. The herald of Zion — the Zionist movement, which strives for the return of Jewish sovereignty — makes its voice heard throughout the world. But what does secular Zionism say? It presses its claim by invoking the right of our nation to self-determination, like all of the nations which claim a right to independence, to self-governance — just like the Poles, the Lithuanians, the Estonians, and so on. Secular Zionism therefore shares its podium with all of the other nations.

The herald of Jerusalem, on the other hand, speaks of the return of Jewish sanctity, of the re-establishment of the Holy City and the Temple. He stands on “a high mountain,” speaking in the Name of God, but his voice is too feeble to be heard. It is as if he were afraid to raise his voice.

Therefore, the prophet turns to the herald of Zion and says, “Why are you standing down there with the other nations, invoking the ordinary ideas of the Gentiles? Go up on a high mountain, speak in the Name of God, in the name of the divine promises, in the name of the prophet’s vision.” And to the herald of Jerusalem, Isaiah says, “You are standing in the proper place and speaking in the name of God, but we cannot hear you; therefore, raise your voice with strength, be not afraid!”

The Western Wall

In a letter dated 16 Tammuz 5705 (1945), Rabbi Ya’akov Moshe Charlap wrote: “When the Rav was in the Diaspora, he would imagine that he was actually at the Western Wall pouring forth his heart before God…. He longed so intensely for the Western Wall that he vowed not to enter any building in Jerusalem before visiting the Wall. And so it was. When he arrived in Jerusalem on 3 Elul 5679 (1919), he bid the large crowd that had come to greet him to disperse. He told them that he had to visit a certain place before settling into the quarters that had been pre- pared for him.

“I accompanied him to the Western Wall. As he approached the alleyways close to the Wall, his face paled and he whispered, ‘How lovely are Your dwelling places, Lord of Hosts. My soul longs, indeed, it faints for the courts of the Lord; my heart and flesh cry out for the living God’ [Ps. 84:2-3]. He approached the great stones of the Wall, rent his garment in mourning, and cried bitterly. He prayed, ‘Reign over the entire world in Your glory,’ and ‘Because of our sins,’ and ‘King of mercy, have mercy upon us.’ Only then did he go to greet the city dignitaries and proceed to his home.”

Aliyah to Har HaBayit

The Rav forbade Jews to ascend the Temple Mount (see Mishpat Kohen, pp. 182ff). In a letter to the British military commander written in 1920, the Rav explained:

“The reason we do not ascend [the Temple Mount] within the Wall is not because we have few rights to the site, but because of our great bond to it and to its exalted holiness. We recognize that as it was when our Temple stood, so, too, today it remains filled with the glory of the Lord, God of Israel, and with His sanctity. But we no longer possess the religious means to make ourselves fit [to ascend], nor will we until the day comes when we shall have everything that is required to make ourselves fit to stand in this holy place to which we are bound with all our soul.

“The Western Wall remains for us a remnant, a sign of our Redemption and of the faith in our return to the sacred status we once enjoyed, when the light of God and the sanctity of prophecy and divine inspiration illuminated our people. Therefore, we feel in this place the most sacred and sublime emotions.”

Mechitza at the Kotel

Through the initiative of the Rebbe of Radzimen, a temporary partition to separate men and women was set up at the Westem Wall on the eve of Yom Kippur, 1929. The Arabs were infuriated. In the middle of the Shemoneh Esrei the following morning, British policemen began to remove the partition. The Jews requested that their prayer not be disturbed, but the British responded with force, beating many of the worshippers. The result was disgrace, pain, and humiliation. This grave incident, as well as the political implications of the quick compliance of the Mandate Government to the Arab complaints and the brutal reaction of the police, angered the entire yishuv. The Chief Rabbinate and other rabbinic courts in Jerusalem proclaimed the eighth of Cheshvan a day of public fasting, prayer, and repentance.

Later that summer, the Arabs rioted at the Western Wall and claimed to be the owners of the sacred site. The Rav wrote an open letter in which he stated:

“The entire educated world knows that the Jews who came to Eretz Yisrael, whether as permanent settlers or as tourists, never ceased to pray at the Western Wall. “The Wailing Wall,” the name acquired in the era of the destruction of the Temple and the exile of the people from the Holy Land, is known by all to refer to the Jewish tears shed there throughout the generations during heartfelt prayer….

“We are hopeful that the tradition of peace and friendship will unite all of the residents of Eretz Yisrael in building the beloved and desolate land. Diligent hands and attentive hearts are required to transform it into a Garden of Eden, into the properly cultured land which it can become through its wondrous, divinely-endowed qualities. Together we shall triumph over all false and fraudulent schemes, all impurity and treachery, which agitators and violent men wish to inflame throughout the Land. We believe that the word of God which declared, “For the Lord will comfort Zion, He will comfort all her waste places; and He will make her wilderness like Eden and her desert like the garden of the Lord; joy and gladness shall be found in her, thanksgiving and the sound of melody” (Is. 51:3) will stand forever, to the joy of all upright in heart among all the nations on earth.”

The Rav hoped that peaceful means could be employed to establish the right to pray at the Western Wall. He wrote:

“We shall attempt to purchase the courtyards near the Western Wall and build there a large, beautiful synagogue administered by the consensus of a majority of rabbis in Eretz Yisrael in a manner acceptable to the entire nation, above any division of rite or custom. The synagogue will testify to our firm anticipation of the forthcoming Redemption, in which the Temple will be speedily rebuilt in our days by the revelation of the glory of God and the light of our righteous Mashiach.”

In the summer of 1930, the League of Nations dispatched a committee to Eretz Yisrael to clarify the ownership of the Western Wall. The Arabs claimed to be the rightful owners, not only of the Temple Mount but of the Western Wall as well, and they rejected outright permitting Jews to pray at the Wall. The British Mandatory government suggested a compromise according to which the Jews would recognize Arab ownership of the Wall and the Arabs, in return, would permit Jews to approach the Wall. (The right to pray at the Wall was not explicitly mentioned.) Due to the tense political situation, the Va’ad Le’umi was prepared to recognize Arab ownership of the Wall, but only if the Arabs would explicitly recognize the right of Jews to pray there. However, because this was a religious matter, the Mandatory Government required that the Va’ad Le’umi’s (the pre-Jewish Agency authority’s) proposal be approved by the religious authority of the Jews, namely, the Rabbinate. A delegation from the Va’ad, headed by Yitzchak Ben Zvi, visited the Rav and tried to persuade him to approve the plan. It is a matter of life and death, they argued, because only by renouncing Jewish ownership will we assuage the Arabs and bring peace to Israel.

But the Rav refused to authorize the proposal. “I cannot relinquish that which God gave to the Jewish people,” he said. “If, God forbid, we give up the Wall, the Holy One, blessed be He, will not wish to return it to us!” As it turned out, the Arabs refused even to consider granting the right of Jewish prayer at the Wall, and the proposal died. Indeed, after the War of Independence, though Article Eight of the ceasefire agreement provided for the right of Jews to approach the Wall, the Arabs ignored it. Only nineteen years later, when God returned the Wall to its original owners in the Six Day War, did we merit once again to pray unhindered at the Western Wall.

“Samuel was Equal to Moses and Aaron”

The 28th of Iyar, the Hebrew date of Jerusalem Day, is also the anniversary of the death of the prophet Samuel.

On the verse “Moses and Aaron among His priests, and Samuel among those who call upon His name” (Ps. 99:6) The Talmud comments: “Samuel was equal to Moses and Aaron” (Berachot 31b). The superiority of an eminent individual manifests itself in two ways: the force of his essential personality and the actions and deeds through which he improves the world. Moses, “the man of God,” primarily affected the Nation through his towering spirituality, while Aaron’s major contribution was his deeds; he loved peace and sought peace (cf. Avot 1:12). But Samuel combined in himself both of these virtues. As the great prophet, he raised the sanctity of the Nation, and as a judge and leader he improved the lives of the masses by spreading the sublime light of Torah among them. Thus, Samuel was equal to Moses and Aaron (cf. Olat Re’iyah II, p. 18).