Rivkah

by HaRav Shlomo Aviner, Head of Yeshivat Ateret Yerushalaim.

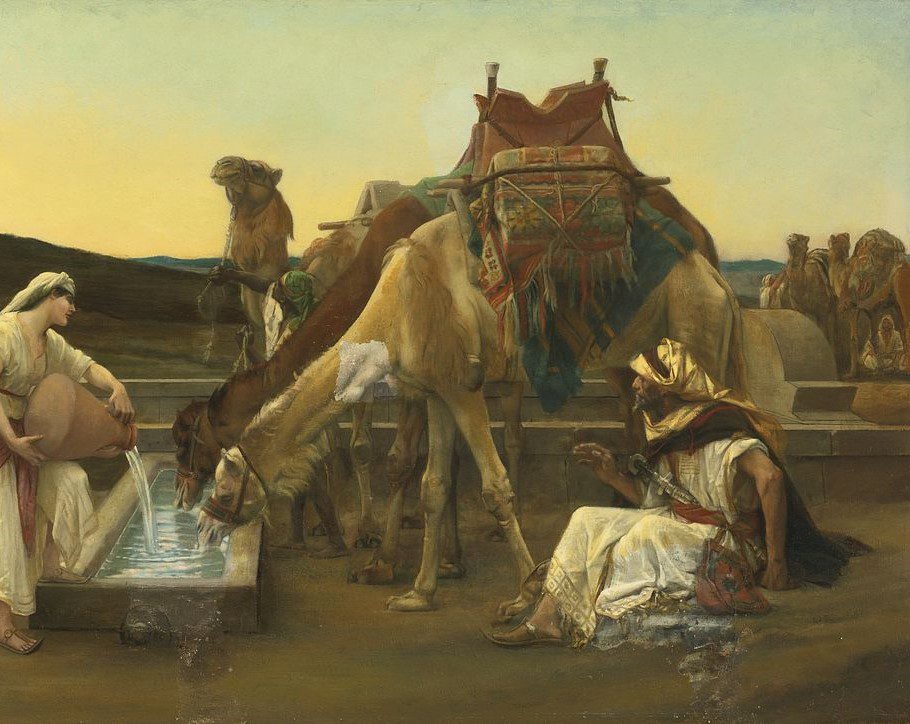

- At the Well of Water

- A Kind Eye

- Resoluteness

- Loving-kindness

- Barrenness

- Blessing of the Children

- And Yitzchak loved Esav

- Blindness and Vision

- Rivkah acted as Intermediary

- For [opposite] his wife

- At the Well of Water

Rivkah was one of the four matriarchs. According to our Sages, there are only four who are called matriarchs: Sarah, Rivkah, Rachel, and Leah (Berachot 16b). She is one of the four foundations of Divinely inspired women of the people of Israel; and her glory resided in her own merit. Prior to her meeting Yitzchak, who would later be her husband, she had an extraordinary character which she displayed by the well of water when she met Eliezer, Avraham’s servant. The Torah sets out a description of the event and repeats it twice though the narration of the servant to Lavan, from which we can understand its importance and learn of Rivkah’s character.

Avraham’s servant assumed a responsibility. Avraham had him swear that he would not choose a wife for Yitzchak from among the women of Canaan, but rather to my land and to my birthplace you will go (Bereshit 24:4). The servant asked Avraham, “Perhaps the woman will not want to follow me to this land, should I bring your son again to the land from which you came?” (ibid. 24:5). However, Avraham did not provide a solution for the situation except for the answer, “Make sure that you do not return my son there” (ibid. 24:6). It is not clear what would have been the fate of the descendents of Israel had the woman not wanted to go with him. Eliezer of Damascus was described by our Sages as being the head of the yeshiva of Avraham our father: “He drew and served drink from his master’s teachings to others” (Rashi on Bereshit 15:2 according to Yoma 28b). He determined on his own the sign by which he could identify an appropriate wife for Yitzchak, following which the extraordinary character of the young woman revealed itself at the well.

According to one of the Midrashim, Rivkah was merely a little girl, three years old (Seder Olam, chapter 1). Based on this calculation, Rivkah was born at the time of the binding of Yitzchak, when he was thirty-seven years old; and three years later, when he was forty, he married her. Rabbi Shmuel Chasid of Shapira explains that she was fourteen years old. His calculation is based on the words of our Sages in Sifri (Ha-Brachah 157) that included among the six pairs whose counterparts lived the same number of years, are Rivkah and Kehat. Kehat lived one hundred and thirty-three years, as did Rivkah; according to this calculation, it is clear that she was fourteen years old when she married Yitzchak (Tosefot on Yevamot 61b). Furthermore, the Torah in its description of Rivkah, says and the young woman was very beautiful, a virgin (Bereshit 24:16). The Gemara says that a virgin (betulah) means a young woman (Yevamot ibid.); and there is no such thing as a beautiful young woman at the age of three, which is an age of childhood.

This young woman revealed herself as being very righteous when she drew water from the well for the servant, despite this being her first encounter with him. The nature of her good deed was such that she performed good deeds for others without any expectation of any reward from anyone. If reward had been the goal, it would not be righteousness but scheming and business. Eliezer was at the well; he could have drawn water for himself and his camels. The young woman could have avoided serving him because it was the time when women came out to draw water (Bereshit 24:11), and there were other young women in the same place. Yet she lowered the bucket (ibid. 24:18), even though the task required great strength; this, despite the fact that he was able to perform it himself. She got him his drink and even did more for him: “I will also draw for your camels” (ibid. 24:19). The ten camels that had traveled from Beersheva to Aram Naharaim drank a huge quantity of water. Nevertheless the man was astonished at her and reflected (ibid. 24:21). He did not lift a hand to help her. Rivkah finished the task; no one stared in amazement at the man for not helping her. She did not say anything, yet when it was over, she invited him to stay over at her house. Eliezer received hospitality which was over and above his expectation (Rashi on Bereshit 24:23). He thanked G-d for the woman whom G-d has designated for my master’s son (ibid. 24:44). Rashi explains, “She is worthy of him for she performs acts of loving-kindness and she is fit to enter the house of Avraham” (Rashi on ibid. 24:14). The house of Avraham our father was a house of loving-kindness; appropriately, it should have received a young woman of loving-kindness. Our Sages considered the sign that Eliezer set for himself: “That the girl who would say I will also give water to your camels” (Bereshit 24:46) would be the young woman specially suited for Yitzchak. This seems to be at first glance reliance on an omen, yet it is forbidden to rely on omen. What is an omen? For example, when they say: In the event my bread falls from my mouth or my staff from my hand, I will not go to such and such place today because if I were to go, I will not get what I want (Rambam, Laws of Idol Worship 11:4; Ravad, ibid.). Similarly, if a black cat crosses my path, I will have an unlucky day. The Maharal explains that an omen is a premise without reason. By contrast, a person who sets out a premise based on logic is not considered to be acting on the basis of an omen. Eliezer established the premise that a young woman who displays righteousness is suitable for Yitzchak. Since this was a logical premise, it in no way constituted reliance on an omen (Gur Aryeh on Bereshit 24:14).

On the surface, it seems that the encounter with Rivkah was a coincidence. Eliezer met the young woman when she was preparing to draw water for him and his camels, as if by coincidence: “Hashem, G-d of my Master Avraham, I pray You send me good fortune” (Bereshit 24:12). But there is no such thing as an accident. The so-called coincidence happened through G-d incognito, in a hidden manner. Lavan himself was grateful and said: “This matter stemmed from G-d” (ibid. 24:50).

- A Kind Eye

Eliezer gazed at the young woman and saw that she was very beautiful (ibid. 24:16). As the young woman’s beauty was not in itself sufficient to render her suitable for Yitzchak our father, he examined her attributes and discovered that she was a righteous person. Eliezer, the best and most experienced teacher, was so stirred that he immediately determined she was fit for Yitzchak. This great man was captured by the charm of righteousness of the young woman he met. The Kli Yikar (on Bereshit 24:14) clearly comments on a passage of our Sages: Any bride who has a kind eye does not required inspection [bedikah] (Ta’anit 24a; Shir Ha-Shirim Rabbah 4:1). Namely, a kind eye is a characteristic of Avraham our father, who looked on everyone kindly (Pirkei Avot 5:19). This means loving everyone, having a desire to do good and teaching merit to everyone. Avraham our father wanted to do good for everyone. His home was open to all four directions of the world in order to welcome guests (See Socher Tov on Tehillim 110; Yalkut Ha-Makiri on Yeshayahu 41:2). When the Master of the Universe prevented visitors from coming to see him after his circumcision, he sat in the doorway of his tent and sent Eliezer to welcome them in the distance (Baba Metzia 86b). His nephew Lot declared, “I want neither Avraham nor his G-d” (Rashi on Bereshit 13:11; Bereshit Rabbah 41:7) for monetary gain. He added sin to iniquity when he chose to live in Sodom among wicked and sinful people (Bereshit 13:13 and Rashi ibid.). Avraham knew all this, yet when he heard he had been taken captive, he armed his trained men (ibid. 14:13), he immediately mobilized his men in order to save him. When G-d informed Avraham that he was about to destroy Sodom, he did not rejoice over the impending deaths of the wicked inhabitants; rather, he haggled with the Master of the Universe, arguing that perhaps there were a number of righteous people on whose account Sodom could be saved (ibid. 18:23-33).

The people of Israel, the descendants of Avraham our father, are merciful, shy and charitable (Yevamot 79a). By contrast, the Givonim were cruel: Therefore there was some doubt about their conversion (ibid.). The Gemara says a cruel person should be examined, because he is not an offspring of Avraham (Beitzah 32b; Rambam, Laws of Forbidden Relations 19:17; Shulchan Aruch, Even Ha-Ezer, 2:2, Be’er Heitev ibid. #5 in the name of the Beit Shmuel). The descendants of Avraham our father forgave with a good heart, a trait which has passed down throughout history.

A story is told about a Jewish doctor who lived in Switzerland during the First World War. Once, late at night, a woman knocked on his door and asked him to urgently examine and treat someone in her house. Take note that she lived in an area of town some distance away; but came to him even though there were excellent doctors in her area. When he wondered about this, she told him: “You are a Jew and so you have a good heart. Surely you would not object to getting up in the middle of the night” (See Le-Netivot Yisrael, chapter 2, p. 247; Sichot Ha-Rav Tzvi Yehudah – Bereshit, p. 168; Vayikra, p. 184; Part 5, Am Yisrael #25; Part 44, Haggadah Shel Pesach #19).

A friend told me he once worked in student admissions at a university in the United States. A young woman, Indian, approached him to say that she specifically wanted to marry a Jew because it was well known that Jews have a good heart and therefore make good husbands.

Rivkah’s charitableness gave her the potential of being a direct continuation of Sarah. Our Sages say that the whole time that Sarah lived, a cloud was hung at the door of her tent; with her death, the cloud lifted. But with the advent of Rivkah, the cloud returned. Once Yitzchak saw that she would carry on the good work of his mother, immediately Yitzchak brought her to the tent of his mother Sarah (Bereshit 24:67; Bereshit Rabbah 60:17). We see a direct link from Chavah, the mother of all living things, to Sarah, and from her to Rivkah as it is said, “The sun rises and the sun sets” (Kohelet 1:5). When The Holy One Blessed Be He caused the sun of Sarah to set, He caused the sun of Rivkah to rise (Bereshit Rabbah 58:2).

- Resoluteness

Let it not be said that Rivkah was a simple maiden who allowed a stranger from far off to take advantage of her good-heartedness; or that she was a young woman with a weak personality who did not know how to refuse. The contrary is true: Rivkah was among the strongest. She lived among wicked people in a place where all were swindlers like her father and brother. She was educated in the homes of the wicked, but remained righteous. She was not weak; rather, her character stood on principle. Our Sages say that Rivkah was like the rose among the thorns (ibid. 63.4). She could not be overwhelmed by her brother or father; but she maintained her beliefs, especially after her marriage to Yitzchak. She established the structure of the home. She was such a strong wife that she was not swayed by her surroundings. Her father and brother knew this, so that when Eliezer sought her hand in marriage for Yitzchak, they said: Let us call the young woman and ask her (Bereshit 24:57). Even though Rivkah was a very young woman, and the convention was that a daughter did what her father wanted, this was not the case of Rivkah. Betuel and Lavan had no interest in sending Rivkah away, and they tried to stall her from going as long as possible. They declared that this matter comes from G-d (Bereshit 24:50), but took the necessary steps to delay (Rabbi Yitzchak Abarbanel): “Let the young woman stay with us a year or ten months” (Bereshit 24:55); and we will try to direct her as to how to answer their request. Lavan and Betuel hoped that Rivkah would be afraid to go far away with a stranger, and to marry someone she had not yet seen. They therefore asked with guile and surprise: “Are you going to go with this man?!” (ibid. 24:58). Yet she responded with one word decisively: “I will go” [Aylech] (ibid.). This was her opportunity to extricate herself from her evil surroundings, and all the more because of what she apparently heard about Yitzchak. Rashi explains her resolute answer, saying: “For myself, even if you do not agree.” The Midrash adds: “I will go even if it is against your will and contrary to your interest” (Bereshit Rabbah 60:12).

Rivkah did not hesitate. She was at ease with the matter and was firm in carrying out difficult acts with resoluteness. Some say this was her defining characteristic, although resoluteness was also prevalent among the other Patriarchs and Matriarchs. In Judaism, doubt is not an ideal. Some think that it is praiseworthy to be doubtful, but the true ideal is to be decisive. A doubter is one without courage. One can think and consider, as long as there is a decision at the end of the day. A person unaccustomed to making decisions for himself should “Find yourself a teacher and avoid doubt” (Pirkei Avot 1:16). If a person is not endowed with spiritual and intellectual powers to arrive at a decision, let him seek help from someone greater than him. Later, our mother Rivkah made the decision for the benefit of Yaakov. He asked and clarified, but in the end, did as she had instructed. He was not a person lacking in character whose movements were dependent on others; rather, the debate and clarification explained things and made it possible to decide and accomplish. All of our forefathers worked with resoluteness. The Torah contains no instance of doubting, of a decision followed by a second thought. Weighing information can take a long time; there are fateful decisions, complications and difficulties. Logic does not operate as a spontaneous instinct. A person needs time to consider, think and decide. Rivkah, however, firmly decided to go with Eliezer, but it appeared that this thought had been percolating inside her for some time. She was like the rose among the thorns, for she knew she had absolutely no interest in marrying one of the wicked men in her area. Her response was rapid and determined, though perhaps it was due to a pre-meditation that had taken a long time.

A story is told about a famous painter who was commissioned by a seller of chickens to paint a chicken for his sign. The sign was to hang on the front door of his store to attract customers. The seller chose the well-known painter because he was interested in a life-like and faithful painting. The painter estimated that it would take a full year to prepare the painting, and stipulated a large amount for his remuneration. The seller was taken aback, but agreed to it. By the end of the year, the painting was not finished and was charging more. Finally, the painter announced that the painting was ready. But when he removed the wrapping, the seller saw that the canvas was empty. The painter then applied some paint on the spot and within a minute, he had painted an extraordinary chicken. The seller of chickens felt he had been deceived; he had paid the painter for more than one year and here he painted the sign in a couple of minutes. But the painter explained to him that during the year he only put his mind to chickens: He had watched chicken coops, ran after chickens and observed them for days on end. It was only after all this effort that he was competent to draw the wonderful chicken.

Over the years, Rivkah contemplated her surroundings, reflected and came to conclusions. This is a positive attribute, provided it does not stem from empty headedness, in which case, it is nothing more than being brazen, strongly asserting opinions with nothing backing them up. On the other hand, resoluteness that comes from great, vast and deep understanding, is courage. The decisiveness of Rivkah stems from the highest ideal of loving-kindness, according to the first story which the Torah relates about her and upon which Rashi (on Bereshit 24:14) and the Maharal (Derech Chayim on Pireki Avot 1:2) comment.

- Kindness

The kindness of Rivkah was filled with resoluteness. She drew water for Eliezer and gave no thought to the impression this act created. This is the mark of kindness: Lack of premeditation. She married and henceforth all of her kindness became focussed on one man, namely Yitzchak. This kindness was equal to a million kindnesses. We are not talking about an ordinary man, but a man at the center of world history, a man of the world, of the whole world. Rivkah went from great private acts of kindness to kindness specifically directed to this man.

Yitzchak, who came from Avraham’s house, was also a man of kindness, although the Torah does not discuss it. He was a private person, a secret righteous person until he was ready to be bound on the altar. The depth of the quality and greatness of this man could not be fathomed until our Sages designated him an unblemished sacrifice [olah temimah] (Rashi on Bereshit 25:2 based on Bereshit Rabbah 64:3). He was a complete unblemished sacrifice, beyond humanity, angelic, beyond angels. According to our Sages, Yitzchak was blinded at the time of the binding on the altar. When his father stretched out his hand for the knife to slaughter him, he did not move or stir. At that very moment, the heavens opened and they saw that the ministering angels were crying; their tears dripped and fell into his eyes, which is why his eyes were dim (Rashi on Bereshit 27:1 based on Bereshit Rabbah 65:10). Yitzchak was on such a high level that even the angels were not able to understand him. Avraham built open homes in his lifetime; he invited guests, planted a tamarisk tree and called upon G-d’s Name. Yitzchak acted in a different way; he was different from his father. His kindness was concealed, his structure invisible and spiritual. He operated in the world in a hidden form, as a hidden righteous person (tzadik). This man who was connected to humanity and the world, became an unblemished sacrifice; and through this experience, spread throughout the whole world the scent of the spice of great kindness, and everyone derived pleasure from his strength. The power of this man’s being in the world brought to everyone a greater sensitivity, righteousness and kindness. This is the nature of a hidden tzadik, who establishes an internal spiritual structure and spreads light to all humanity. The Maharal explains that Yitzchak differed in this righteousness from Avraham, as well as from Rivkah (Derech Chayim on Pirkei Avot 1:2). Rivkah was thoroughly kind-hearted, in her activity and conduct. Yitzchak withdrew into himself. All his activity was hidden, as was his awesome self-sacrifice in being bound on the altar. This was something that happened within him, and therefore not evident to others. Yet he caused a revolution in world history for all generations, and no one can describe its scope.

- Barrenness

Yitzchak and Rivkah are said to have different personalities and perhaps this is the reason for her barrenness. Their relationship was such that it was not possible for them to bear children. Rivkah gave up loving-kindness for herself so she could dedicate herself to universal loving-kindness, while he delayed for several years, almost twenty years (Bereshit 25:20-26). Indeed, even Avraham and Sarah had no children, resulting in Sarah giving Avraham her maidservant to have offspring through her (ibid. 16:1-3). Not so with Yitzchak and Rivkah. He was an unblemished sacrifice; he could not do what his father did (Rashi on Bereshit 25:26). He waited; he did not even pray. Yitzchak understood that their succession was complicated, and that difficult and intricate matters are slow in resolving themselves. Only after twenty years did he pray. The hidden face of G-d revealed itself even after Rivkah conceived. Difficulties followed, for the sons fought within her (Bereshit 25:22). Even in this situation, Yitzchak did not intervene. The struggle had no connection with his spiritual world. But for Rivkah, it was different: “And she went to inquire of G-d” (ibid.). Her inquiry was not a question of curiosity or despair, but a need to understand what she had to do. This is the meaning of the phrase: “If so, why am I this way” (ibid.)? And her situation was not simple. The Holy One Blessed Be He announced to her the new forces that would arise from her: “Two nations are in your womb: Two peoples from your belly shall be separated; power will pass from one to the other and the elder will serve the younger” (ibid. 25:23). The internal struggle evidenced the archetypal war between the two sons. Our Sages says: The Holy One Blessed Be He never speaks with a woman unless she is righteous (Bereshit Rabbah 63:7; Socher Tov on Tehillim 9:7).

- Blessing of the Children

Rivkah oversaw the activities in Yitzchak’s house; she established the structure of the house; she planned and carried out her plans (Sichot Ha-Rav Tzvi Yehudah – Bereshit, p. 220, 232), and received Yitzchak’s support for her conduct. When Eliezer brought her to Yitzchak, he reflected and received her. When she went to inquire of G-d, he was in accord. Even when she caused him to give the blessing for Esav to Yaakov, he was happy with what she had done: “For he will also be blessed” (Bereshit 27:33). Yitzchak was a person who was under the umbrage of heaven: At the binding through Avraham our father; at the marriage arrangement, through Eliezer; and at the blessing of the sons through Rivkah. He was a man of secrets in the order of a spirit took me up (Yechezkel 3:12), guided by the winds of heaven. His interaction with events in the world was not at all by chance, but was guided by an understanding that events unfold according to a Divine plan. After the reversal of the blessings between Yaakov and Esav, we do not hear of any anger or rebuke directed against Rivkah by him about her daring plan. Esav wondered: “Father, do you have one blessing” (Bereshit 27:38)? But Yitzchak left things as they were. With a strong spirit, he succeeded in recognizing that whether events unfold by accident or against his will, it is the will of The Holy One Blessed Be He.

The real question is why Rivkah tricked Yitzchak. If according to her view Yaakov should have been blessed, why did she not openly discuss the issue with him? Perhaps they would have debated the matter until he was persuaded. It is evident that even very righteous people are not always easy to persuade. Great scholars sat in the Sanhedrin, and one could not always succeed in persuading the other, which is why issues were decided by a majority vote. Rivkah knew that his position on the subject of the sons’ blessings was different than hers. She disregarded Yitzchak’s position, which was contrary to hers, because there was no possibility of persuading him otherwise. She decided she knew that in this matter her power was greater than that of Yitzchak. When Yaakov asked her, “Perhaps my father will feel me” (ibid. 27:12), she responded, “The blame will be on me” (ibid. 27:13): My son, I will be responsible for your curse. I know that you must be the one to receive the blessing and not your brother Esav, even though Yitzchak disagrees with me. And Yitzchak agreed that this is the way these things had come about. The disparity between the views of Yitzchak and Rivkah understandably was only in regard to the blessing for material wealth which she diverted through wisdom and cunning from the hands of Esav: “May the Lord grant you of the dew of the heaven and of the fat of the earth” (ibid. 27:28). Yitzchak passed on to Yaakov the supreme blessing of Avraham without any competitor (ibid. 27:3-4). Yitzchak and Rivkah were both Divinely inspired but of opposite personalities: This is the reason for the difference in their attitude toward the sons. He was Divinely inspired in secrecy, sublimity and simplicity, while she was Divinely inspired in a revealed way.

We should understand the propriety of what Rivkah did. She did not control Yitzchak and structure his life. Quite the opposite, Rivkah was in awe of him, possessed by a strong fear of the holy. When she met him for the first time, she dismounted from the camel (ibid. 24:64). When she saw this man, who had been bound to the altar, she was in awe, amazed at his character. Our Sages say that what she saw in him was the image of a heavenly angel (Socher Tov, Mehadurat Buber, Tehillim 90:18). There is a reference in the order of the sacrifices of Yom Kippur to the effect that when the four-lettered name of G-d was heard issuing from the mouth of the High Priest in sanctity and purity, the people would prostrate themselves (Mishnah, Yoma 66a). They had no specific intent in prostrating; rather, the very force of hearing the Divine Name caused them to prostrate on the ground. When Rivkah saw the Divine Name cleave to Yitzchak’s personality, she prostrated herself. Her sending of Yaakov to receive the blessing from Yitzchak bore witness to the fact that she believed there was power and absolute truth in Yitzchak’s blessing. She recognized the majestic strength of Yitzchak, and was filled with awesome admiration; she set up the whole ruse so that Yaakov would be vested with the great benefit of the blessing. Rivkah was filled with shame in standing before Yitzchak as we see described in their first meeting: So she took a veil and covered herself (Bereshit 24:65). She was self-effacing before him, but not in all matters. In the matter of the blessing which was fateful and affected the very foundation of the Jewish People, she was not passive; on the contrary, she maneuvered to have Yaakov receive it.

- And Yitzchak Loved Esav

Yitzchak did not receive any joy from Esav. He understood that Yaakov was the more pious man, who lived in tents, and that being a hunter was not the ideal life. It therefore caused him grief that his son Esav was a hunter all his life, and never dwelt in tents. We have here an instructive approach to and Yitzchak loved Esav (ibid. 25:28). When a son does not behave properly, one must teach him through a difficult educational process; one must love him and bring him closer. Esav was not interested in tents, in piety, or in the right of the firstborn: “And Esav squandered his birthright” (ibid. 25:34). But after much persuasion, Esav was prepared to support Yaakov, to ensure that venison would always be in his mouth, meaning that Yitzchak was prepared to compromise and not to hate Esav if he would concern himself with the material well-being of Yaakov (Sichot Ha-Rav Tzvi Yehudah – Bereshit, p. 220, 232).

However, The Holy One Blessed Be He said: “And I hated Esav” (Malachi 1:3). How could Yitzchak love Esav when G-d hated him? Rather, it is written “And I hated Esav” meaning that I hate the attributes of Esav, the immoralities and negative traits that characterize Esav. Yet deep down, Esav was good. The essence of Esav’s goodness was his ability to deal with the hidden world within himself. This is the explanation of the Vilna Gaon on the dictum of our Sages that Esav’s head was buried in the Cave of Machpelah (Likutei Ha-Gra at the end of Sa’arat Eliyahu). His head, the face, the upper part was connected to the Cave of Machpelah. Even Yaakov understood this. After he fought the whole night with the angel of Esav, he said, “For I saw G-d face to face” (Bereshit 32:30). Even Esav had a Divine aspect, which will be revealed in the future, and then brotherly love will appear (Igrot Ha-Re’eiyah vol. 1, p. 142).

- Blindness and Vision

Esav’s essence will only manifest itself in the future; and in this regard, Yitzchak was blind. Certainly this is not a reference to physical blindness, for generally speaking a blind person develops acute feelings and senses which enable him to orient himself in his surroundings; all the more so a great scholar like Yitzchak. For example, the Gemara relates a story about Rav Sheishet who was blind; yet in spite of his blindness, was more perceptive than those who could see (Berachot 58a). There are people with eyes who see nothing; and there are those whose vision is impaired, so to speak. But they see very clearly everything that happens around them. Rabbi Nachman of Breslov relates in one of his stories that there were seven beggars. One of them was a blind man who saved children. At the end of the story, the beggar explains that in general no one is blind. Rather, the whole world is ephemeral, everything is like the blink of an eye; so there are things that hide from them, and there is no connection with them. It is useless to watch things that pass and disappear. He only sees a fixed and eternal goal and has no connection with a negative passing phenomenon.

In this perspective, Yitzchak our father was blind. Yitzchak knew that Esav in his essence was good and would be good. His fundamental core was good. Yitzchak did not look at the momentary. He did not base his position on things that were passing, that changed and were temporary; even if that temporariness was thousands of years. Yitzchak’s perspective was based on the eternal. Yitzchak was blind in regard to temporary matters. He could see, but only things that were fixed and eternal. For Esav, there was a place in the world. His head was in the Cave of Machpelah. The hatred of him was the manifestation of a momentary negativity, his temporariness. His essence was good, and so Yitzchak wanted to bless him.

- Rivkah Acted as Intermediary

Rivkah had powerful insight. She knew that Esav had hidden magnificent strengths that would be revealed in the future. But she also knew that they would not surface in the near future; indeed it was impossible to determine exactly when. As of that time, the moment had not yet arrived; accordingly, Esav was not worthy of a blessing. Therefore, she arranged matters so that Yaakov would get the blessing. However, she was a person of great loving-kindness and she also sought wisdom and clarity.

Rivkah was one of the seven barren women, corresponding to the seven days of Creation. She corresponds to the second day of which it is said: “And there was separation between the waters” (Bereshit 1:6; Kehilat Yaakov – erech Rivkah). She was endowed with the strength to discern, who separates the holy from the profane, the light from darkness, and Israel from the nations (Havdalah; Pesachim 103b). In the future, we will all be one family; in the meantime, it is not so. This is where Rivkah and Yitzchak disagreed. Yitzchak’s essence was the truth, but for all practical purposes, its time had not yet come. In fact, Rivkah did not really differ with Yitzchak; she merely made things clear for him. Our Sages say that Rivkah was the intermediary between Yitzchak and The Holy One Blessed Be He, so that Yitzchak would bestow the blessings (Bereshit Rabbah 67:2). The Master of the Universe sent a blessing to Yaakov through Yitzchak. Rivkah worked to make sure that the blessing would come to the intended. Yitzchak agreed with her being an intermediary. We see a similarity in the relationship between the Written Torah and the Oral Torah. It is written in the Torah: “Eye for an eye” (Shemot 21:24; Vayikra 24:20), but the Oral Torah explains that this means monetary compensation (Baba Kama 84a; See Sichot Ha-Rav Tzvi Yehudah – Shemot, pp. 234-235). Yitzchak wanted to bless Esav and Rivkah interpreted: In the meantime, let him bless Yaakov.

Yitzchak accepted Rivkah’s position. He determined: “The voice is the voice of Yaakov, but the hands are the hands of Esav” (Bereshit 27:22). Certainly, it was easier to put on a sheepskin on his hands than to change his voice. Some understand the voice of Yaakov as not referring to pitch. After all, Yaakov and Esav were twins and it was reasonable to assume that they had an identical voice. Yaakov did not suspect that his father would identify his voice, but he worried: “Perhaps my father will feel me” (ibid. 27:12). However, Yaakov’s voice had a certain way of phrasing and content to his words. He spoke with refinement: “Please rise…Because Hashem, your G-d, brought it for me” (ibid. 27:19-20). This was the style of conversation of Yaakov, and Yitzchak identified it, even though in reality, the hands were like the hands of Esav. Yitzchak said: “The scent of my son is like the scent of the field” (ibid. 27:27). Up to that point, it seemed Esav would be favored, but then he continued: “Whom G-d has blessed” (ibid.). It appears that Yitzchak understood Rivkah’s maneuver, and immediately acknowledged it. For he accepted and agreed it had come from heaven. He perceived things through the Divine inspiration that imbued him, and he blessed Yaakov.

- For [Opposite] His Wife

One should understand that even though Yitzchak and Rivkah had opposite personalities, they were united all the way. It is written, “and Yitzchak entreated G-d for [opposite] his wife” (ibid. 25:21). This means he stood in this corner and prayed, and she stood in another corner and prayed (Rashi ibid. based on Bereshit Rabbah 63:5), and they prayed together. The mystics calculate that Yitzchak spoke two hundred and forty-nine words. This refers to the words of the blessing which were not his but were spoken by G-d from the depth of his throat, leaving one hundred sixty-three words. This is exactly the number of words which Rivkah spoke.

The appearance of Yitzchak and Rivkah rectified the damage done by Adam and Chavah, which had punished Chavah: “And he will rule over you” (Bereshit 3:17). From the beginning of the world until this very day, the fact is that men dominate women, sometimes with a cruel hand. The strength of Yitzchak and Rivkah remedied this situation. Yitzchak in no way dominated Rivkah. Since childhood, it was impossible to dominate her. Even her father and brother could not control her. Yitzchak had no interest in dominating her; on the contrary, from the beginning in the Torah it says: “She became his wife and he loved her” (ibid. 24:67). This is not a description of a relationship of dominance, but of love. However, Yitzchak was an inward man, an unblemished sacrifice on the altar, yet it specifically says of him that he loved her. Even this love was secretive, internal, intimate, a deep love and it would not be disrupted for anything. It is written that Yitzchak was sporting with his wife Rivkah (ibid. 26:8). When the same term sporting [matzchaik] is used in regard to Yishmael (ibid. 21:9), it has a negative connotation. In regard to Yitzchak, by contrast, it confirms his intimate and internal greatness. Even though he was tied to the altar, the bond between him and his wife surpassed all. The love of Yitzchak did not suffer disruption: Twenty years had passed without their having children, and not every man could have withstood such a test.

Rachel told Yaakov: “Give me children, otherwise I am dead” (ibid. 30:1). But the response of Yaakov is equally very harsh: “Am I in G-d’s stead” (ibid. 30:2)? Our Sages criticize Yaakov for his answer because no one should respond in such a way to a depressed person (Rashi ibid. based on Bereshit Rabbah 71:7). Even though Rachel did not have to speak the way she did, the problem was depressing her and she needed understanding. Similarly, there was tension between Avraham and Sarah born of her barrenness. Sarah wanted Avraham to send away the maidservant, which was inappropriate in his eyes. The tension was resolved when he was told: “Everything that Sarah tells you, heed her voice” (Bereshit 21:12).

Despite the infertility, there was no tension between Yitzchak and Rivkah. They had no children, but Yitzchak did nothing about it. He had a true strength of love which did not wane in the face of any challenge. Even after Rivkah sent Yaakov to receive the blessing, there was not even a hint that the incident had adversely affected the love between them. Rivkah considered that Yitzchak had an extraordinary worth and she knew the power of his blessing. She knew that Yitzchak saw the situation through an eternal perspective, so that he had to bless Esav. She was not capable of changing his mind but her mind was made up; therefore, she carried out her plan with a belief that it was her duty. And Yitzchak accepted it without criticism.

Yitzchak’s name connotes the future. “He will laugh” [yitzchak], in the future tense. His perspective was directed to the future, to what would be. He was above time and its events, yet he was also inside time “Yitzchak was sporting [yitzchak matzchaik] with his wife Rivkah” (ibid. 26:8). That corrupt person, Avimelech, watched them from the window (ibid.). Avimelech did not understand the meaning of the principle that a man’s wife is his sister, as it is written in Shir Ha-Shirim (8:1): “O that someone would make you as my brother.” Avraham tried to explain it to Pharaoh, and Yitzchak to Avimelech: The latter stared through the windows of his understanding, and on that same day, he understood the quality of love that existed between husband and wife.

Yitzchak and Rivkah definitely had opposite personalities: He, a man of secrets withdrawn within himself who perceived and understood generations and worlds; and she, his wife possessed with Divine inspiration watching over the management of her household, with an immediate and earthly practicality.

The difference did not destroy the love and the bond between them; and together, they rectified the misfortune of “And he will rule over you,” which was one of the four curses Chavah received; because each one of the curses were rectified by one of the Martriarchs (see above, pp. 24-26). Rivkah’s rectification was not done by the command of Yitzchak, but for [lenochach] or together with Yitzchak.

This rectification was laid down for mankind and as a fundament of life by the Jewish People who do not practice, “And he will rule over you” (see Ma’amrei Ha-Re’eiyah vol. 1, p. 192). Our role is to reveal this power of Rivkah that which is hidden in reality within us. This is an example of the dictum that what happens to the fathers is a sign for the sons (Ramban on Bereshit 12:6, 12:10); the strength of the fathers is found in the sons.