The Art of T’shuva

by Rabbi David Samson and Tzvi Fishman [Based on the book “Orot HaT’shuva” by HaRav Avraham Yitzhak HaKohen Kook.]

This is how Rabbi Kook begins his book “Lights on T’shuva” –

“For some time now, I have been struggling with an inner battle. A powerful force is impelling me to speak on the subject of t’shuva. All of my thoughts are concentrated on this. The greatest part of the Torah and life is devoted to the matter of t’shuva. All of the hopes of the individual and the community are founded upon it. T’shuva is a Divine commandment which is both the easiest, since the thought of t’shuva is considered t’shuva in itself (Kiddushin 49B), and on the other hand, it is the most difficult commandment, since its essence has not yet been fully revealed in the world and in life.”

He continues: “I find myself constantly thinking and wanting to speak exclusively about t’shuva. Much has been written on the subject of t’shuva in the Torah, the Prophets, and in the writings of our Sages, but for our generation, the matters are still obscure and require clarification…. My inner essence compels me to speak about t’shuva. And yet I am taken aback by my thoughts. Am I worthy enough to speak about t’shuva? However, no shortcoming in the world can discourage me from fulfilling my inner claim. I am driven to speak about t’shuva….”

The book “Art of T’shuva” is a reader-friendly commentary on selected essays from Rabbi’s Kook pivitol treatise on the phenomenon of T’shuva. Rabbi David Samson was a longtime student of HaRav Tzvi Yehuda Kook and is one of Israel’s foremost educators, a veteran teacher at the Mercaz HaRav High School Yeshiva, and founder and director of 5 high schools for “youth at risk” in Israel. His co-writer, Tzvi Fishman, a baal t’shuva who made aliyah from Hollywood, is a graduate of the Machon Meir Yeshiva in Jerusalem. He has authored some 20 books on a variety of Jewish themes.

Rabbi Kook writes:

“With each passing day, powered by the lofty light of t’shuva, the penitent’s feeling becomes more secure, clearer, more enlightened with the radiance of sharpened intellect, and more clarified according to the foundations of Torah. His demeanor becomes brighter, his anger subsides, the light of grace shines on him. He becomes filled with strength; his eyes are filled with a holy fire; his heart is completely immersed in springs of pleasure; holiness and purity envelop him. A boundless loves fills all of his spirit; his soul thirsts for G-d, and this very thirst satiates all of his being. The holy spirit rings before him like a bell, and he is informed that all of his willful transgressions, the known and the unknown, have been erased; that he has been reborn as a new being; that all of the world and all of Creation are reborn with him; that all of existence calls out in song, and that the joy of G-d infuses all. Great is t’shuva for it brings healing to the world, and even one individual who repents is forgiven, and the whole world is forgiven with him.”

The following is an abridged version of the book “The Art of T’shuva” based on Rabbi Kook’s teachings. Happy t’shuva!

THE AGE OF ANXIETY

It is no secret that there is great darkness, confusion, and pain in the world. Bookstores are filled with self-help books on how to be happy. Layman’s guides to psychology line shelf after shelf. Our generation has been called “the age of anxiety.” People often live out their lives plagued with depression, sickness, a sense of non-fulfillment and constant unrest. Psychiatrists, psychologists, and humanists have become the prophets of the moment, proposing dozens of theories to explain man’s existential dilemmas. Whether it is because we suffer from an Oedipus complex, or from a primal anxiety at having been separated from the womb, from sexual repression, or from the trauma of death, mankind is beset with neuroses. Vials of valium and an assortment of anti-depressants and “uppers” can be found in the medicine cabinets of the very best homes. Not to mention the twenty-four-hour bombardment of work, television, computer games, Facebook, Internet surfing, and drugs which people use to blot out the never-ending angst that they feel.

Rabbi Kook understands all of this darkness and anguish. He sees its source not in external causes, not in the traumas of childhood, nor in the pressures to conform to behavioral norms. He looks beyond social, cultural, psychological, sexual, and family dynamics to shed spiritual light on the world’s confusion and pain. In his book, “Orot HaT’shuva,” Rabbi Kook writes:

“What is the cause of melancholy? The answer is the over-abundance of evil deeds, evil character traits, and evil beliefs on the soul. The souls deep sensitivity feels the bitterness which these cause, and it draws back, frightened and depressed.”

“All depression stems from sin, and t’shuva comes to light the soul and transforms the depression to joy. The source of the general pain in the world derives from the overall moral pollution of the universe, resulting from the sins of nations and individual man.”

“Every sin causes a special anxiety on the spirit, which can only be erased by t’shuva. According to the depth of the t’shuva, the anxiety itself is transformed into inner security and courage. The outer manifestation of anxiety which is caused by transgression can be discerned in the lines of the face, in a person’s movements, in the voice, in behavior, and one’s handwriting, in the manner of speaking and one’s language, and above all, in writing, in the development of ideas and their presentation.”

The melancholy and anxiety haunting mankind is not a result of the “trauma of birth,” but of a spiritual separation much deeper — the separation from G-d.

“I see how transgressions act as a barrier against the brilliant Divine light which shines on every soul, and they darken and cast a shadow upon the soul.”

The remedy is t’shuva — for the individual, the community, and for the world. Rabbi Kook teaches that to discover true inner joy, every person, and all of Creation, must return to the Source of existence and forge a living connection to G-d.

The paperbacks on personal improvement, psychology, and self-help which line bookstore shelves, contain many useful insights and tips. After all, man is influenced by a wide gamut of factors dating back even before his conception, through his time in the womb, his childhood years, and spanning the many life passages each of us face. Rabbi Kook reveals that in addition to all of the fashionable theories and cures, on a far deeper level, there is a spiritual phenomenon of wondrous beauty, like a butterfly enclosed in a cocoon, waiting to soar free. This is the light and healing wonder of t’shuva.

T’SHUVA MAKES THE WORLD GO ROUND

The Gemara teaches that t’shuva existed before the world was created. In a similar vein, Rabbi Kook writes that the spirit of t’shuva hovers over the world and gives it its basic form and the motivation to develop. It is t’shuva which gives the world its direction and its inner energy to constantly progress. The desire to refine the world and to embellish it with beauty and splendor all derive from the spirit of t’shuva.

T’shuva is the Divine, spiritual force in the universe which is constantly propelling all of existence toward perfection. It is the voice of God calling, “Return to Me, you children of men.” Due to the “separation” from God through transgressions, improper living, or through the act of Creation itself, there is a constant drive in all things to return to a harmony with their Maker. Rabbi Kook writes that, “It is impossible to express this awesomely deep idea.” The force of t’shuva, like gravity in the physical world, is built into the inner fabric of life. It stands as the impetus behind all human history, all world development, all endeavor toward social improvement. It is the force which inspires all cultural, artistic, and scientific advancement. Similarly, the yearning of mankind for universal justice and moral perfection is a product of the encompassing, ever-present power of t’shuva.

On a personal level, when a man sells his house in the country because he wants to improve the quality of his life, he is involved in t’shuva. When a family has a fun and relaxing vacation, they are being motivated by forces of t’shuva. Though there may be underlying factors of profit and self-interest when a pharmaceutical company produces a new drug, they too are involved in t’shuva, if their product truly helps to benefit the world.

“T’shuva derives from the yearning of all existence to be better, purer, more fortified and elevated than it is. Hidden within this desire is a life-force capable of overcoming that which limits and weakens existence. The personal t’shuva of an individual, and even more so of the community, draws its strength from this source of life which is constantly active with never-ending vigor.”

Never-Ending T’shuva

In his writings, Rabbi Kook illuminates the phenomenon of t’shuva in an entirely new fashion. Here we encounter the notion of t’shuva, not as personal penitence alone, but as an ever-active force in the world which constantly works to unite all things with God.

“The currents of specific and general t’shuva flood along. They resemble waves of flames on the surface of the sun, which break free and ascend in a never-ending struggle, granting life to numerous worlds and numberless creatures. It is impossible to grasp the multitude of colors of this great sun that lights all worlds, the sun of t’shuva, because of their abundance and wondrous speed, because they emanate from the Source of life itself….”

In his poetic style, Rabbi Kook describes t’shuva like a sun which sends out constant flames of warming light to the world. Just as G-d has created the sun as life’s principle energy source, so too is t’shuva the spiritual energy source of existence. T’shuva does not only operate when a person decides to mend his erring ways – t’shuva exists all of the time. It exists both within man and all around him, as a personal t’shuva, and as a t’shuva which comes from Above. Like gravity, or the wind, or the rays of the sun, t’shuva is ever present. It is a constant force always at work, bringing the world to completion. One day the force may hit Jonathan; the next day Miriam; one day soon it will uplift the Jewish people as a whole. Its waves flow by us in a continuous stream. Minute by minute, the song of t’shuva calls out to us to hurry and join in the flow.

TIKUN OLAM

Now that we recognize that t’shuva is an independent force which G-d has implanted into the fabric of Creation, we must ask, what does it do?

Throughout his writings on t’shuva, Rabbi Kook has to clothe his profound understandings in a wardrobe of metaphors to express the workings of t’shuva.

“The individual and the collective soul, the world soul, the soul of all worlds of Creation, roars like a mighty lioness in agony for complete perfection, for the ideal existence; and we experience the pain, and it purges us like salt sweetens meat, the pain sweetens our bitterness.”

Rabbi Kook emphasizes that the soul has a built-in motor that guides it toward perfection. The perfection it seeks is the union with God. This is what King David is expressing when he says, “Of Thee my heart has said, Seek My Presence. Thy Presence, Hashem, I will seek.”

One unites with God when one has a knowledge of God and performs His will. God’s will is housed in this world in the Torah and its commandments. Thus, the reunion with God, for the individual, and for the Jewish People in its ideal national format, means a return to the Torah, in the place where the Torah is meant to be kept – the Land of Israel.

What empowers the soul to seek out its Maker? What gives it fuel for the quest? The power of t’shuva. Rabbi Kook explains:

What empowers the soul to seek out its Maker? What gives it fuel for the quest? The power of t’shuva. Rabbi Kook explains:

“Through the force of t’shuva all things return to God. By the existence of t’shuva’s power which prevails in all worlds, all things are returned and reconnected to the realm of Divine perfection. Through concepts of t’shuva, understandings of t’shuva, and feelings of t’shuva, all thoughts, ideas, understandings, desires, and emotions are transformed and return to their essential character in line with Divine holiness.”

Before continuing, it may be beneficial to say a few words about the concept of returning to G-d. What does this mean? Where have we gone that we need to return? This is a very profound question, and only the beginnings of an answer will be given here. The soul, in its essence, belongs to the world of souls. When it is placed in this world, in a physical body, it naturally longs to go home. For the soul, going home is being reunited with God. One of the great innovations of Judaism is the teaching that this reunion is not limited to the return of the soul to Heaven after the death of the body. Unlike other religions, Judaism teaches that the soul can find union with God in this world. This union is brought about when a Jew performs the Torah’s commandments.

The expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden describes man’s existential plight. In effect, the sum of world history is mankind’s journey to return to the Garden. Not only man, but the world itself wants to return to its original state. This yearning is one of the most powerful forces of Creation. Thus the world “roars like a mighty lioness” to return to its original, ideal closeness to God.

Once we understand that the goal of existence is to be reunited with God, and that the force of t’shuva is at work all of the time, we can understand that the t’shuva of the individual over specific sins, and the encompassing t’shuva of the world longing for perfection, all stem from the same essential drive.

“General t’shuva, which is the uplifting of the world to perfection; and specific t’shuva, which relates to the particular personality of each individual, including the smallest items needing improvement in all of their details… they are both of one essence. So too, all of the cultural reforms which lift the world out of moral decay, along with social and economic advancements, and the mending of all transgression… all of them comprise a single entity, and are not detached one from the other.”

The perfection of all of the different people and ideologies in the world really represents one giant unified t’shuva. To understand this deep idea, it may help to momentarily substitute another word for t’shuva when we speak about the t’shuva of culture, society, and ultimately of the world. Instead of the word t’shuva, let’s use the word geula, or redemption. To Rabbi Kook, t’shuva and redemption share the same direction and goal — to bring healing to a suffering world. Redemption is the ever-active historical process which brings the Nation of Israel and the world to perfection and completion. The zenith of redemption is reached at the End of Days with the arrival of Mashiach and Israel’s great material and spiritual Renaissance. When this great day arrives, the Kingdom of God will be established throughout the world; Israel will be recognized as His truly chosen people; the nations will flock to Jerusalem to learn the laws of the God of Jacob; and Divine truth and justice will reign supreme. In this glorious future, prophecy will be reestablished in Israel, and life itself will experience the zenith of t’shuva when the dead are resurrected from their graves.

Using the concept of redemption to illuminate our understanding of world perfection, we can better appreciate Rabbi Kook’s great vision of t’shuva.

“With each second, in the depths of life, a new illumination of supreme t’shuva shines ever forth, just as a new glowing light constantly sparkles through all realms of existence and replenishes them…. The fruit of the highest forms of moral and practical culture, blossom and grow in the flow of this light. In truth, the light of the whole world and its renewal in all of its forms, in every time and age, depends on t’shuva. This is especially true regarding the light of Mashiach, the salvation of Israel, the rebirth of the Jewish Nation and its Land, language, and literature — all of them stem from the source of t’shuva, and all will emerge from the depths to the exalted reaches of the highest t’shuva.”

T’shuva and redemption are parallel processes, reaching the same destination. The main difference between them is one of style and not of substance. For example, redemption has a broad historical, international base with political consequences. Though there are differences between them, these two phenomena are closely intertwined, so that when Rabbi Kook speaks about the t’shuva of the entire world, he is speaking about its overall moral, material, and spiritual redemption.

As we shall see, it is the Nation of Israel, in its return to its original Torah life in the Land of Israel, which is destined to lead all of mankind back to God.

Lightning-Like T’shuva

Rabbi Kook explains that t’shuva comes about in two distinct formats, either suddenly, or in a gradual, slowly developing fashion. Both of these pathways to t’shuva are readily found in the baal t’shuva world. Some people will tell you how their lives suddenly changed overnight. Others describe their experience as a long, challenging process which unfolded over years. Many factors influence the way in which t’shuva appears, including personality, background, and environment. Health problems, whether physical or psychological, can inspire a person toward t’shuva. Personal tragedy — a death in the family, or the loss of one’s job, can trigger sudden revelations of t’shuva. For others, a seemingly chance encounter with a religious Jew, a Sabbath experience, or a visit to the Kotel in Jerusalem, have all been known to set the stirrings of t’shuva in motion. Even dramatic current events, like catastrophes or wars can influence awakenings of t’shuva.

What stands out in Rabbi Kook’s teaching is that the potential for t’shuva is ever-present. Like light from the sun, the waves of t’shuva constantly envelop the earth. Its spiritual force empowers mankind, silently working to bring the world back to God. Some people jump on the t’shuva train in one bold leap. Others climb aboard in a much slower fashion. But the train itself is always in motion.

What stands out in Rabbi Kook’s teaching is that the potential for t’shuva is ever-present. Like light from the sun, the waves of t’shuva constantly envelop the earth. Its spiritual force empowers mankind, silently working to bring the world back to God. Some people jump on the t’shuva train in one bold leap. Others climb aboard in a much slower fashion. But the train itself is always in motion.

Concerning sudden t’shuva, Rabbi Kook writes:

“Sudden t’shuva results from a spiritual bolt of illumination which enters the soul. All at once, the person recognizes the ugliness and evil of sin, and he is transformed into a new being. Already, he feels within himself a total change for the good. This type of t’shuva derives from a certain unique inner power of the soul, from some great spiritual influence whose ways are best sought in the depths of life’s mysteries.”

Sudden t’shuva appears when a person suddenly decides that his entire way of living needs to be changed. Revolted by the impurity of his ways, he abruptly sets out on a purer, healthier course. All at once, he feels that everything in his life must be transformed. A sudden burst of great light reveals the sordidness of his existence, and he understands that an entire life overhaul is in order — new habits, new friends, new interests, new goals. Seemingly overnight, he is a new person. Of course, the sudden break from his old ways is not cut and dry. A person cannot change his whole existence at once. The process may take a day or a decade. But the decision which triggers this great transformation occurs in a moment of profound revelation and cleansing. A sudden, cathartic illumination lights up his being, and he is changed.

A discussion in the Gemara alludes to this type of split-second t’shuva (Kiddushin 49B). There is a law that if a man marries a woman on the basis of some condition, the marriage is legal only if the condition is met. If a man were to say, “You will be my lawfully-wedded wife on the condition that I will give you one-hundred dollars,” if he gives her the money, they are married. If he does not give her the money, then the marriage does not take place. What happens if a man were to marry a woman on the condition that he is a completely righteous person? Suppose that the man is a known evildoer. If he makes his righteousness the basis for the marriage, is the marriage considered proper and legal?

Jewish law states that the woman is “safek mekudeshet,” meaning that she is married out of doubt. Yet if we know that the man is evil, how can this be? After all, the marriage was based on the condition that he be as righteous as a tzaddik. It should follow that since the condition was not kept, the woman is not married. The Gemara explains: “We are cautious for maybe he had a contemplation of t’shuva.”

We learn from this that repentance can be a split-second decision. One can become a penitent in a second, through the thought of t’shuva alone. This is what Rabbi Kook is alluding to when he speaks about sudden t’shuva. Very often people are afraid to embark on a course of repentance because they believe it involves years of suffering and difficult change. Here we learn the opposite. T’shuva is easy!

The Talmud teaches that in the End of Days, God is going to do away with man’s evil inclination (Sukkah 52A). Seeing this, both the righteous and evildoers react by weeping. The righteous cry when the evil inclination is shown to be as large as a mountain. The knowledge that they had to spend their lives overcoming such a formidable foe brings them to tears. The wicked cry when it is revealed to them that the evil inclination was in reality an insignificant opponent. It could have been conquered by a split-second of t’shuva, but that opportunity is now forever lost. We learn from this that the seeming darkness of sin can be swiftly erased by the great light and wonder of t’shuva.

Here are some examples of sudden t’shuva. A person one day decides, “That’s it. I am going on a diet starting today. I want to be healthy.” He strides into the kitchen and throws out all of the candies, ice creams, sodas, and chocolates. Cans of food loaded with colorings and chemical preservatives go flying into the trash. He joins a health club, moves to a place where the air is clean, and starts each new day with a jog before dawn.

Or the baal t’shuva suddenly decides that he is fed up with the wheeling and dealing; he is weary with the struggle to get around the law; he is ashamed for the income he has failed to report; he is disgusted with his infidelities and lies. “That’s it,” he declares. “No more. From now on, I am going to be an honest, moral person.”

Alternately, a brilliant, sudden flash of t’shuva can leave a person disgusted with the false patterns of behavior, ideologies, and false religions which he is following. As if awakening from a nightmare, he takes a deep breath, suddenly driven to align his life with the Divine truth of existence. His flash of sudden light inspires him to say, “Wow, have I been wasting my life! What a fool I have been! And I thought I was being smart! That’s it. The past is forgotten. From now on, I am getting my life together with Torah!”

In contrast, gradual t’shuva differs from sudden t’shuva in its less dramatic, more step-by-step form. Often, when we speak about baale t’shuva, we are referring to people whose lives have been changed overnight. Gradual t’shuva, on the other hand, is something which often appears in a person who generally lives his life in a healthy, positive fashion. When he falls into error or sin, his recovery is more gradual, without the overwhelming illumination that comes to a person whose life has been saturated by darkness. Rabbi Kook writes:

“There is also a gradual type of t’shuva. The change from the depths of sin to goodness is not inspired by a brilliant flash of light in one’s inner self, but by the feeling that one’s ways and lifestyle, one’s desires, and thought processes must be improved. When a person follows this path, he gradually straightens his ways, mends his character traits, improves his deeds, and teaches himself how to correct his life more and more, until he reaches the high level of refinement and perfection” (Orot HaT’shuva, Ch.2).

An already moral person who feels he is still far away from the goal he longs to reach, will set off on a gradual climb toward t’shuva. For him, the process of return does not revolutionize his life all at once. Rather, his perfection demands a step-by-step course of improvement. Indeed, for the average person, the best way to climb a great mountain is by taking a lot of little steps.

When this type of person goes on a diet, he does not rush into the kitchen and throw out all of the unhealthy foods all at once. Knowing that it will take time and a great deal of willpower to wean himself away from the sweets that he loves, he resolves to be fat-free within another six months. Every day, he tries to eat one donut less. He sits down and draws up a chart, starting with one push-up and working, day-by-day, to fifty. He does not suddenly revamp his whole life. Rather, he changes it a little at a time. In this manner, he can set his life on a healthier course without dramatically altering his current comforts and habits.

Gradual t’shuva also applies in the realm of moral perfection. Character traits are not easy to alter. If one proceeds too fast by jumping to the opposite extreme, he can cause himself harm. For instance, if a greedy person decides that he has to be generous and gives all of his money to charity at once, he will not have anything left for himself. Similarly, while anger is an extremely negative trait, it is also not healthy to be unemotional and indifferent. At first, a leap to the other extreme might be helpful in effecting a change, but then the penitent should gradually work his way back to the middle (Rambam, Laws of Knowledge, 2:2). The Gaon of Vilna recommends that in turning a negative trait into a positive one, it is wise to set a gradual course toward reaching the middle ground between the extremes. Because the change comes about slowly, a strong foundation is built. New behavior patterns formed in this fashion are likely to survive the challenges and frustrations which people face every day. In contrast, something which comes quickly, like sudden t’shuva, might, in some cases, also disappear quickly as well.

In regard to religious belief, gradual t’shuva often appears when a person strives to merge his life with the Divine Plan for existence. Generally, a bond and commitment to religion evolves slowly. After all, accepting the yoke of the Torah’s commandments is not a simple matter. Not only must one’s lifestyle be altered, but the list of do’s and don’ts seems overwhelming. Of course, this is the view of the uninitiated, as seen from the outside. Once a person steps inside the world of Judaism, what seemed frightening in the beginning becomes a fountain of great delight. Nonetheless, the path out of darkness to the light of the Torah is usually a slow, step-by-step journey, as opposed to the rocket ship of sudden t’shuva. First a person comes to feel respect for the Jewish religion. He comes to appreciate the great wisdom and beauty of Jewish tradition. He realizes that Judaism has shaped the Jewish Nation, protected it throughout the generations, and given it its character. But at this early stage, he is not yet ready to embrace all of the precepts of Judaism and make them a part of his life.

Then, the more a person experiences Judaism and is stirred by its spirit, the more he cherishes it. Feeling the great warmth of Jewish tradition, he begins to relate to it like a long-lost friend. Motivated by the positive feelings which he now experiences upon each encounter with Judaism, he begins to study its teachings in depth. His knowledge of Judaism increases. More and more, he finds himself stimulated by the Divine genius he discovers within it. Delving into its depths, he finds beauty and joy in all of the commandments.

Finally, convinced of the Torah’s Divine origin and truth, he begins to practice all of its teachings. He runs to perform the mitzvot with zest and enthusiasm. Nothing else in the world affords him such contentment and happiness.

The question can be asked, which of the two paths of t’shuva brings greater enlightenment — sudden or gradual. Rabbi Kook answers:

“The higher t’shuva results from a lightning-like flash of goodness, of the Divine good which dwells in all worlds, of the light of He who is the life of the worlds. The noble soul of all existence is pictured before us in all of its splendor and holiness to the extent that the heart can absorb. Is it not true that everything is so good and upright, and that the uprightness and goodness that is within us, does it not come from our being in harmony with everything? How can we be severed from the wholeness of existence, a strange fragment, scattered into nothingness like dust? From this recognition, which is truly a Divine recognition, comes t’shuva out of love, in the life of the individual and in the life of mankind as a whole.”

The Path to Happiness

T’shuva can happen suddenly, in a burst of illumination which wondrously transforms life’s darkness to light, or it can evolve over time, gradually returning the body, psyche, and soul to the true Divine path of existence.

Rabbi Kook explains that t’shuva appears in two different penitential forms: t’shuva over a specific sin or sins; and a general, all-encompassing t’shuva which completely transforms a person’s whole being and life.

If general t’shuva can be compared to a complete car overhaul, where the entire motor is removed and replaced, then specific t’shuva is like a tune-up of engine parts, a spark plug here, a cable there, new brake fluid, oil and anti-freeze.

Specific t’shuva is commonly referred to as penitence. It is the t’shuva familiar to everyone, whereby a person sins, feels guilty, and decides to redress his wrongdoing. Rabbi Kook believes in the basic goodness of man. In his natural, moral, pristine state, man is a happy, healthy creature. When a man sins, his natural state is altered, and the difference causes him pain. Sin causes a distortion. It creates a barrier between man and his natural pure essence and source. Most essentially, sin damages man’s connection to God. The feeling which results, whether we call it anxiety, pain, darkness, guilt, sickness, or remorse, impels the sinner to correct his wrongdoing, in order to return to the proper course of living. The sorrow which stems from transgression acts as an atonement, and the sinner is cleansed. Returned to his original state of wellbeing, the melancholy and darkness of sin is replaced by the joy and light of the renewed connection to goodness and God.

“There is a type of t’shuva which focuses on a specific sin, or many specific sins. The individual confronts his wrongdoing directly, regrets it, and feels sorry that he was ensnared in the trap of transgression. Then his soul climbs and ascends until he is freed from sinful bondage. He feels in his midst a holy freedom which brings comfort to his weary soul. His healing proceeds; the glimmers of light of a merciful sun, shining with Divine forgiveness, send him their rays, and, together with his broken heart and feelings of depression, a feeling of inner happiness graces his life….”

There are times in everyone’s life when a person decides to change a particular habit, to improve a trait, or to right some outstanding wrong. He is not looking to change his whole life. Generally he is content, but he senses a need to remedy a specific failing. If a person realizes that he is stingy, he may decide that he wants to be more charitable. Or he may feel a pressing need to return a tennis racket which he stole. In the same light, a religious person may realize that his prayers lack enthusiasm and proper concentration. So he sets out to pray with more fervor. In these cases, his t’shuva deals with a specific life problem which he sets out to correct.

A person whose soul is sensitive to moral wrongdoing will feel remorse for his sins. The remorse weighs down on him, and he longs to break free from its shackles. The longing to redress his wrongdoing works like a force to shatter the darkness, opening a window of light. This light of t’shuva is a stream of Divine mercy. It is as if God reaches out and accepts the penitent’s remorse. The sin is forgiven. The path back to God has been cleared. Instead of darkness and gloom, happiness envelops the soul.

“He experiences this (happiness) at the same time that his heart remains shattered, and his spirit feels lowly and sad. In fact, this melancholy feeling suits him in his situation, adding to his inner spiritual gladness and his sense of true wholeness. He feels himself coming closer to the Source of life, to the living God, who had been so distant from him a short time before. His longing spirit jubilantly remembers its former inner pain, and, filled with emotions of gratitude, it raises its voice in song and praise: ‘Bless the Lord, O my soul, and do not forget all of His goodness; He forgives all thy iniquities, heals all thy diseases; redeems thy life from the pit; adorns thee with love and compassion; and satiates thy old age with good, so that thy youth is renewed like the eagle’s. The Lord performs righteousness and judgment for all who are oppressed’” (Tehillim, 103: 2-6. Orot HaT’shuva, 3).

The person who sins and feels remorse senses its cleansing power. He recognizes his pain as an atonement, and this brings him relief. Almost miraculously, the clouds of his transgression are lifted, and the light of t’shuva fills his being with joy. He senses that it is G-d who has freed him, and his heart abounds with gratitude and song.

In describing the inner workings of t’shuva, Rabbi Kook does not enumerate the many halachic laws of repentance which can be found in other books. For instance, the Rambam’s Laws of T’shuva sets forth the steps a person must take in redressing transgression. Among the many details, a penitent must confess his sin, feel remorse, abandon his wrongdoing, amend his ways, and never commit the transgression again (Rambam, Laws of T’shuva, 2:2). Rabbi Kook presumes that his reader has a knowledge of these laws. His goal is to illuminate the overall phenomenon and importance of t’shuva in the life of the individual, the Jewish Nation, and the world.

Summing up his analysis of specific t’shuva, Rabbi Kook describes a journey from darkness to light:

“How downtrodden was the soul when the burden of sin, its darkness, vulgarity, and horrible suffering lay upon it. How lowly and oppressed the soul was, even if external riches and honor fell in its portion. What good is there in wealth if life’s inner substance is poor and stale? How joyful the soul is now with the inner conviction that its iniquity has been forgiven, that God’s nearness is living and glowing inside it, that its inner burden has been lightened, that its debt (of atonement) has already been paid, and that it is no longer anguished by inner turmoil and oppression. The soul is filled with rest and rightful tranquility. ‘Return to thy rest, O my soul, for the Lord has dealt bountifully with thee’” (Tehillim, 116:7).

Interestingly, the process of anguish, depression, catharsis, and joy which Rabbi Kook describes parallels the psychiatric journey, or the quest for happiness in our time. Vast numbers of people are depressed and unhappy. The world’s pleasures can only bring them a few fleeting moments of delight. Their lives are plagued by darkness, anxiety, and inner despair. Modern psychiatry, and all of the popular books on the subject, offer a gamut of explanations, solutions, treatments, and cures. They too promise psychic release and joy. But all too often, after some initial relief, the patient is back on the couch, or back in the bookstore searching for the newest bestseller.

In Rabbi Kook’s explanation of specific t’shuva and general t’shuva, what strikes us is his understanding of human psychology. While psychiatrists offer many theories about man’s existential dilemma and angst, Rabbi Kook reveals that the real cause of humanity’s malaise stems from mankind’s severance from God. The solution, he teaches, is t’shuva.

As we study Rabbi Kook’s explanation of general t’shuva, how remarkably it sounds like a description of the anxiety and spiritual darkness of our age:

“There is another type of feeling of t’shuva — a vague, general t’shuva. Past sin or sins do not weigh on a person’s heart. Rather he has a general feeling of profound inner depression, that he is filled with sin, that God’s light does not shine on him, that there is nothing noble in his being. He senses that his heart is sealed, and that his personality and traits are not on the straight and desirable path that is worthy of gracing a pure soul with a wholesome life. He feels that his intellectual insights are primitive, and that his emotions are mixed with darkness and lusts which awake within him a spiritual repulsion. He is ashamed of himself; he knows that God is not within him; and this is his greatest anguish, his most frightening sin. He is embittered with himself; he can find no escape from his snare which involves no specific wrongdoing – rather it is as if his entire being is imprisoned in dungeon locks.

“From out of this psychic bitterness, t’shuva comes as a healing plaster from an expert physician. The feeling of t’shuva — with a deep insight into its working and its deep foundation in the recesses of the soul, in the hidden realms of nature, in all the chambers of Torah, faith and tradition — with all of its power, comes and streams into his soul. A mighty confidence in its healing, the encompassing rebirth which t’shuva affords to all who cling to it, surrounds the person with a spirit of grace and mercy.”

This description of depression, darkness, inner shame and despair is an exact description of modern man’s psychic condition. Whether it is termed psychological neurosis by Sigmund Freud, primal angst by Carl Jung, anxiety by Rollo May, or feeling not-OK by Thomas Harris, the symptoms are the same.

Thus, when Joe Cohen walks gloomily into a bookstore looking for a paperback bestseller on how to be happy, he should also look for a book on t’shuva. Before phoning a shrink, he should have a good, long talk with a rabbi.

In emphasizing that t’shuva is the cure for mankind’s anxiety and depression, we do not intend to negate the contributions of psychology and its related fields. Psychology has its place. For instance, an insecure youth will experience a feeling of liberation when he realizes that his parents are smothering him. The feelings of repressed anger which were causing him depression now can be dealt with. Similarly, when a man in couples-therapy realizes that he feels in competition with his wife because of unresolved childhood hang-ups with his brother, he will feel liberated to embark on a healthier marriage. However, while childhood traumas influence behavior and cause great confusion and pain, when they are finally uncovered and resolved, the catharsis which results is only a step along the way. Until an individual erases all of the “neuroses” or barriers which separate him from God, he will remain estranged from his self, imprisoned in darkness, living either like an unfeeling zombie, or in depression and pain. Psychology and its branches can give him a start, but ultimately, the only real cure is t’shuva.

“With each passing day, powered by this lofty general t’shuva, his feeling becomes more secure, clearer, more enlightened with the light of intellect, and more clarified according to the foundations of Torah. His demeanor becomes brighter, his anger subsides, the light of grace shines on him. He becomes filled with strength; his eyes are filled with a holy fire; his heart is completely immersed in springs of pleasure; holiness and purity envelop him. A boundless loves fills all of his spirit; his soul thirsts for God, and this very thirst satiates all of his being. The holy spirit rings before him like a bell, and he is informed that all of his willful transgressions, the known and the unknown, have been erased; that he has been reborn as a new being; that all of the world and all of Creation are reborn with him; that all of existence calls out in song, and that the joy of God infuses all. Great is t’shuva for it brings healing to the world. When even one individual who repents is forgiven, the whole world is forgiven with him” (Yoma 86B. Orot HaTshuva, 3).

Thus, general overall t’shuva does not come to mend anything specific. It occurs when a person feels lost, surrounded by darkness, and cut off from God. In this drastic state, a total revamping is needed. The rotted foundations of this person’s lifestyle must be uprooted, and a new Divine foundation be built in its place. But where does one start? First by longing. By longing for God. This leads to prayer, a calling out for God from the darkness. Indeed, the search for a holier life will bring a person to discover two life-saving essentials of t’shuva — prayer and Torah. Prayer is man’s ladder to God. By expressing man’s longing for his Maker, prayer builds a bridge between the physical world and the spiritual world. Once a connection has been made, man can begin to hear the “voice” of God calling back. God communicates with man through the Torah. The Torah is God’s will for the world, His plan for our lives. Discovering Torah, man discovers true light. Finally, he knows what to do. He knows how to act. With the guidelines of Torah, he learns to distinguish between good and evil, between pure and impure. In the past, his life was guided by his own ethical sense and desires, without ever knowing what was truly moral and just. Suddenly the darkness and uncertainty are gone. Anxiety vanishes. In the light of the Torah, his soul finds instant rest, secure that it has found the right path. Once again united with the Divine song of existence, he brings himself, and the whole world, closer to God.

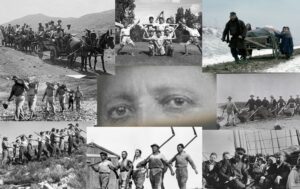

T’SHUVA BRINGS HEALING TO THE WORLD

As we previously learned, mankind is always involved in t’shuva. The fact that there are many non-religious people today should not be held as a contradiction. T’shuva must be looked at in an encompassing perspective that spans all generations.

A story about Rabbi Kook may help illustrate this. One day, he was walking by the Old City in Jerusalem with Rabbi Chaim Zonnenfeld, one of the leading rabbis of the Ultra-Orthodox community.

“Look how awful our situation is,” the Rabbi observed. “See how many secular Jews there our in the city. Just a few generations ago, their father’s fathers were all Orthodox Jews.”

“One must look at Am Yisrael in a wider perspective,” Rabbi Kook answered. “Do you see this valley over here, the Valley of Hinom? This was once a site for human sacrifice. Today, even the crassest secularist will not offer his child as a human sacrifice for any pagan ideal. When you look at today’s situation in the span of all history, things do not seem so bad. On the contrary, you can see that there has been great progress.”

The Rambam, at the end of the Laws of Kings, refers to this same development process of redemption which encompasses all things in life. He asks the question — if Christianity is a false religion, why did God grant it so much dominion? In the time of the Rambam, Christianity and Islam ruled over the world. The Jews suffered miserably under both. The Rambam’s answer is based on a sweeping historical perspective which finds a certain value in Christianity, even though the Rambam himself classifies Christianity as idol worship (Laws of Idol Worship, 9:4, uncensored edition). On the one hand, he emphatically condemns Christianity, and on the other hand he maintains that Christianity has a positive role in the development of world history. How are we to reconcile this contradiction?

The Rambam writes that Christianity serves as a facilitator to elevate mankind from the darkness of paganism toward the recognition of monotheism. In effect, it is a stepping stone enabling mankind to make the leap from idol worship to the worship of God. The belief in an invisible God does not come easily to the masses. Christianity, weaned mankind away from the belief in many gods to a belief in a “three-leaf clover” of a father, a son, and a holy ghost. Once the world is accustomed to this idea, though it is still idol worship, the concept of one supreme God is not so removed. Furthermore, the Rambam writes that Christianity’s focus on the messiah prepares the world for the day when the true Jewish messiah will come. Today, because of Christianity’s influence, all the world, from the Eskimos to the Zulus, have heard about the messiah, so that when he arrives, he will have a lot less explaining to do. “Oh, it’s you,” mankind will say on the heralded day. Though they will be surprised to find out that it’s not Jezeus, they’ll say all the same, “We’ve been waiting for you.”

Thus, when world history is looked at in an encompassing perspective, even Christianity, with all of its many negative factors, can be seen to play a positive role in mankind’s constant march toward t’shuva.

When we understand this historic, all-encompassing perspective, we can see that a world movement like Christianity, despite all of its evil, can influence the course of human history toward a higher ideal. But how does one man’s t’shuva bring redemption closer? How does a person’s remorse over having stolen some money bring healing to the cosmos as a whole?

The answer is that we are to look on each individual, not as a unit separated from the rest of the world, but as being integrally united with all of Creation. Rabbi Kook writes:

“The nature of the world and of every individual creature, the entire sweep of human history and the life of every person, and his deeds, must be viewed from one all-encompassing perspective, as one unity made up of many parts…” (Orot HaT’shuva, 4:4).

A man is not a fragmented being disconnected from the past and the future. He is part of the continuity of generations. He is a part of his national history and a sweeping world drama. In the same way that he is a product of his past, he is also the seed of the future. When a man sees himself in this wider perspective, the t’shuva he does for personal sins is magnified by his connection to all generations. Thus, his personal t’shuva is uplifted by the general t’shuva of the world, which strengthens his own drive to do good. This merging of an individual’s t’shuva with the mighty stream of the universal will for goodness is the source of the great joy which t’shuva always brings.

“T’shuva comes forth from the profoundest depths, from the vast depths where the individual is not a separate entity, but rather a continuation of the greatness which pervades universal existence. The yearning for t’shuva (on a personal level) is connected to the world’s yearning for t’shuva at its most exalted source. And since the great current of the flow of life’s yearning is directed toward doing good, immediately many streams flow through all of existence to reveal goodness and to bring benefit to all” (Ibid, 6:1).

For example, as a wheel axis spins, the spokes and the whole wheel spins with it. So too, a person who steals should not look at his theft as his own personal dilemma, he should see his stealing as something that damages the moral environment around him, and this adds evil to the society where he lives, and this increases the evil in the world. When he starts returning the money he took, he adds goodness to the world and brings all of existence closer to moral perfection. Like a stone thrown into a pool, his individual t’shuva sends waves of t’shuva rippling through all realms of life, from his family and immediate surroundings, to his community, his nation, and the world. Because his soul is attached to the soul of the world, in purifying his soul, he helps purify all realms of being.

Thus, Rabbi Kook writes that it is impossible to quantify the importance of practical t’shuva, and the correcting of one’s behavior in accordance with the Torah, which raises the soul of the individual and the soul of the community to higher and higher levels. Every step along the way contains myriads of ideals and horizons of light.

This understanding led our Sages to say that “Great is t’shuva, for it brings healing to the world,” (Yoma 86A) and “even one individual who repents is forgiven and the whole world is forgiven with him” (Ibid 86B).

“The more we contemplate to what extent the smallest details of existence, the spiritual and the material, are microcosms containing the general principles, and understand that every small detail bears imprints of greatness in the depths of its being, we will no longer wonder about the secret of t’shuva which so deeply penetrates man’s soul, encompassing him from the beginning of his thoughts and beliefs to the most exacting details of his deeds and character” (Orot HaT’shuva, 11:4).

When a man understands that his personal t’shuva advances the process of Redemption of the world, his motivation to mend his own life is enhanced. His own personal t’shuva expands beyond his life’s limited boundaries and brings benefit to all of mankind. No longer dwelling on escaping his own personal darkness, he altruistically yearns to bring greater illumination to the world. This is the zenith of t’shuva.

THE WORLD’S GREATEST JOY

Jews who have become religious, baale t’shuva, describe t’shuva as the most joyous experience in their lives. Very often, a gleam of happiness shines in their eyes. Their speech is filled with an excited ring, as if they have discovered a secret treasure. Even people who have tasted all of life’s secular pleasures insist that the experience of t’shuva is the world’s greatest joy.

What is the reason for this? What is the source of this joy? Rabbi Kook writes:

“T’shuva is the healthiest feeling possible. A healthy soul in a healthy body must necessarily bring about the great joy of t’shuva, and the soul consequently feels the greatest natural pleasure” (Orot HaT’shuva, 5:1).

First, it is important to note the connection which Rabbi Kook makes between t’shuva and health. As we previously learned, a healthy body is an important foundation of t’shuva. Contrary to the picture of the penitent as a gloomy, frail, bent-over recluse who shuns the world, the true baal t’shuva is healthy, happy, robust, and bursting with life.

When a person rids himself of bad habits, like overeating and cigarette smoking, his health is improved. Without these harming elements, he is stronger and more vibrant. So too, when one rids oneself of bad moral habits and base character traits, his spiritual health is improved. Without these negative influences, his soul is free to receive the flow of Divine energy and light which fills the universe. When he is both physically and spiritually healthy, his capability to experience the Divine is greatly enhanced. It is this “meeting with God” that brings the influx of joy that every baal t’shuva feels. When the unhealthy walls which had separated him from God are eliminated from his life, he stands ready for life’s greatest discovery — the discovery that God and the spiritual world are real. Suddenly, God’s love and kindness surround him. All his sins are forgiven. Instead of darkness, there is light all around him and a pool of endless love. Rabbi Kook writes:

“In measure with every ugly thing which a person eliminates from his soul when he inwardly longs for the light of t’shuva, he immediately discovers worlds filled with exalted illumination inside his soul. Every transgression removed is like the removal of a blinding thorn from the eye, and an entire horizon of vision is revealed, the light of unending expanses of heaven and earth, and all that they contain” (Ibid, 5:2).

The new spiritual horizons which the baal t’shuva discovers give him a feeling of freedom, as if he were soaring through air. This new-found freedom comes when the walls blocking God’s light have been razed. The baal t’shuva is freed from the bad habits and passions which had enslaved him in the past. He escapes from a web of wrongdoing. The lack of godliness which had pervaded his actions, his thoughts, and his being, is erased. Freed from his darkness, he can experience the wonders of God.

“The steadfast will to always remain with the same beliefs to support the vanities of transgression into which a person has fallen, whether in deeds or in thoughts, is a sickness caused by an oppressive slavery that does not allow t’shuva’s light of freedom to shine in its full strength. For it is t’shuva which aspires to the original, true freedom — Divine freedom, which is free of all bondage” (Ibid, 5:5).

Once again, we may be startled. People often think that in discovering God, one is restricting one’s freedom, not expanding it. If one recognizes his Creator, he also has to recognize His laws. For a person who thinks this way, religion is perceived as a yoke of responsibility and bondage. But Rabbi Kook tells us the opposite. The discovery of God is the ultimate freedom. Finally, a person is liberated from beliefs that he held on to in order to justify his errant lifestyle. Finally, he is freed from cycles of behavior which he could not control. Like a criminal who decides to go straight, he can now put his life in line with God’s will for the world. This is the greatest freedom!

Often people are afraid to set out on a course of t’shuva because they associate repentance with pain. While pain is a part of the t’shuva process, the hardships of t’shuva are quickly erased by the joy which the baal t’shuva discovers.

“T’shuva does not come to make life bitter, but to make it more pleasant. The happy satisfaction with life that comes with t’shuva is derived from the waves of bitterness which cling to a person during the initial stages of t’shuva. However, this is the highest, creative valor, to recognize and understand that pleasantness evolves out of bitterness, life out of the clutches of death, eternal pleasures out of sickness and pain. As this everlasting knowledge grows and becomes clearer in the mind, in the emotions, in the person’s physical and spiritual natures, the person becomes a new being. With a courageous spirit, he transmits a new life force to all of his surroundings. He spreads the good news to all of his generation, and to all generations to be, that there is joy for the righteous, and that a joyous salvation is certain to come. ‘The humble also shall increase their joy in the Lord, and the poorest among men shall rejoice in the Holy One of Israel” (Ibid, 16:6).

We will explore the connection between t’shuva and pain in more detail in further essays. Here, it is important to note that the pain a person feels when he confronts his sins and his unholy past is only a temporary phase of t’shuva. It resembles the pain of surgery, when a disease must be cut out of the body. The uprooting of sin brings healing and joy in its wake, but the initial amputation is painful. It is difficult to give up the familiar, even if it be an evil habit. When a person understands this and opens himself up to change, he comes to be filled with a courageous new spirit and joy. His sins are forgiven. His life is renewed, and the world seems to be renewed with him. Immediately, he wants to share his good fortune with everyone. He tells his parents with a gleam in his eyes, as if he has met the right girl. With unbounded enthusiasm, he phones his brother long distance to turn him on to the great secret which he has discovered. He is so hopped up on t’shuva, he wants the whole world to know. “Hey everybody, listen to me. You want to be happy? You want to be high? Get with it. Don’t do drugs. Do t’shuva!”

THE HEROES OF T’SHUVA

If there was a guaranteed deal that by shelling out 15 dollars, you would get 15 million dollars in return, would you do it? Of course you would. Well, that’s exactly what T’shuva is.

We learned that the joy of t’shuva comes from removing the barriers of transgression and melancholy which separate a person from God. Another reason why the joy of t’shuva is so great is because the happiness of t’shuva is felt in the soul. Until a person discovers t’shuva, he experiences the pleasures of the world on the physical, emotional, or intellectual levels alone. He enjoys good foods, stimulating books, new clothes and the like. But a man has a deeper, spiritual level of being, his soul, which derives no satisfaction from earthly pleasures.

“To what is this analogous? To the case of a city dweller who marries a princess. If he brought her all that the world possessed, it would mean nothing to her, by virtue of her being a king’s daughter. So it is with the soul. If it were brought all the delights of the world, they would be nothing to it, in view of its pertaining to the higher elements” (Mesillat Yesharim, Ch.1).

When a person does t’shuva, he opens his soul to a river of spiritual delight. The joy he discovers is like nothing which he has ever experienced. Not only are his senses affected, t’shuva touches his soul. Just as his soul is deeper than his other levels of being, the happiness he discovers is deeper. Just as his soul is eternal, his joy is eternal. Unlike the transitory pleasures of the physical world, the joy of t’shuva is everlasting. A jacuzzi feels good, but when it is over, the pleasure soon fades away. But in the heavenly jacuzzi of t’shuva, you don’t just get wet — you get cleansed and transformed. Thus, Rabbi Kook writes:

“When the light of t’shuva appears and the desire for goodness beats purely in the heart, a channel of happiness and joy is opened, and the soul is nurtured from a river of delights” (Orot HaT’shuva, 14:6).

This river of delight is the river of t’shuva. Rabbi Kook’s use of this expression is not metaphorical alone. In the spiritual world, there actually exists a river of t’shuva. (For the Kabbalists among you, it’s the wellsprings of Binah flowing to us through the now t’shuva-unclogged river of the Yesod). This is the constant flow of t’shuva which, though invisible, is always present and active. It is our channel to true joy and happiness because it is our channel to God. Nothing in the world can compare to its pleasures. Rabbi Kook explains:

“Great and exalted is the pleasure of t’shuva. The searing flame of the pain caused by sin purifies the will and refines the character of a person to an exalted, sparkling purity until the great joy of the life of t’shuva is opened for him. T’shuva raises the person higher and higher through its stages of bitterness, pleasantness, grieving, and joy. Nothing purges and purifies a person, raises him to the stature of being truly a man, like the profound process of t’shuva. In the place where the baale t’shuva stand, even the completely righteous cannot stand” (Berachot 34B. Orot HaT’shuva, 13:11).

The real hero is not the Hollywood tough guy. It isn’t the man who smokes Marlboro cigarettes. It isn’t the corporate president who owns a Lear jet and three yachts. The true man is the person involved in t’shuva. Rabbi Kook teaches, “The more a person delves into the essence of t’shuva, he will find in it the source of heroism” (Ibid, 12:2). This is similar to the teaching of our Sages, “Who is a hero? He who conquers his evil inclination” (Avot, 4:1). He is the person who is always seeking to better himself; the person who is always trying to come closer to God. He is the person who is open to self-assessment and change; the person who has the courage to confront his soul’s inner pain and to transform its bitterness into joy.

The real hero is not the Hollywood tough guy. It isn’t the man who smokes Marlboro cigarettes. It isn’t the corporate president who owns a Lear jet and three yachts. The true man is the person involved in t’shuva. Rabbi Kook teaches, “The more a person delves into the essence of t’shuva, he will find in it the source of heroism” (Ibid, 12:2). This is similar to the teaching of our Sages, “Who is a hero? He who conquers his evil inclination” (Avot, 4:1). He is the person who is always seeking to better himself; the person who is always trying to come closer to God. He is the person who is open to self-assessment and change; the person who has the courage to confront his soul’s inner pain and to transform its bitterness into joy.

“T’shuva elevates a person above all of the baseness of the world. Notwithstanding, it does not alienate the person from the world. Rather, the baal t’shuva elevates life and the world with him” (Orot HaT’shuva, 12:1).

Sometimes, people have a misunderstanding of t’shuva. They think that t’shuva comes to separate a person from the world. While some baale t’shuva make a point of isolating themselves completely from secular society, this is not the ideal. During the early stages of t’shuva, a person should certainly avoid situations which are antithetical to his newfound goals, in order to rebuild his life on purer foundations, but a baal t’shuva is not a recluse. He should not cut himself off from the world. The opposite. By participating in the life around him, he elevates, not only himself, but also the world. After returning to God, he must return to the world. By doing so, he returns holiness to its proper place, and makes God’s Presence sovereign in the world. Rabbi Kook writes: “Tzaddikim should be natural people, and every aspect of their bodies and beings should be characterized by life and health. Then, through their spiritual greatness, they can elevate all of the world, and all things will rise up with them” (Arpelei Tohar, pf.16).

God created the heavens for the angels. Our lives are to be lived down on earth. It is our task to bring healing and perfection to this world, not to the next. When the powerful life-force which went into sin is redirected toward good, life is uplifted. A baal t’shuva who returns to a former situation in which he sinned, and now conducts himself in a righteous, holy manner, affects a great tikun. The Rambam writes: “For instance, if a man had sinful relations with a woman, and after a time was alone with her, his passion for her persisting, and his physical powers unabated, while he continued to live in the same district where he had sinned, and yet he refrains and does not transgress, he is a baal t’shuva” (Laws of T’shuva, 2:1). He is like a gunslinger who mends his ways and comes back to town to do away with the bad guys. Because of his t’shuva, Dodge City is a better, safer, more wholesome place.

“The inner forces which led him to sin are transformed. The powerful desire which smashes all borders and brought the person to sin, itself becomes a great, exalted life-force which acts to bring goodness and blessing. The greatness of life which emanates from the highest holy source constantly hovers over t’shuva and its heroes, for they are the champions of life, who call for its perfection. They demand the victory of good over evil, and the return to life’s true goodness and happiness, to the true, exalted freedom, which suits the man who ascends to his spiritual source and essential Divine image” (Orot HaT’shuva, 12:1).

It is time to take t’shuva out of the closet. The true champions of life are not the basketball players, not the Hollywood stars, not even the Prime Ministers and Presidents. The real heroes are the masters of t’shuva. They are the Supermen who battle the forces of darkness in order to fill the world with goodness and blessing. Teenagers! Tear down your wall posters of wrestlers and rock stars! The people to be admired are the masters of t’shuva! You can be one too!

THOUGHTS MAKE THE MAN

T’shuva may seem like a towering mountain too high to climb, but it’s really not as hard as you think.

Rabbi Kook teaches that even contemplations of t’shuva have significant value. To understand this, we must look at life with a different orientation than we normally do. Usually, we are pragmatists. We judge the value of things by the influence they have on ourselves and the world. For instance, ten dollars is worth more than five dollars because it can buy more. A doctorate is better than a bachelor’s degree because it can lead to a better paying and more prestigious job.

There are things, however, that have an absolute value, regardless of their tangible impact in this world. Truth is an example. Holiness is another. To this list, Rabbi Kook adds good thoughts. Contemplations of t’shuva, even if they do not lead to a resulting change in behavior, bring benefit to the individual and the world.

This is similar to the question in the Talmud — which is greater, Torah study or good deeds? The answer is Torah study because it leads to good deeds. You might think that if the ultimate goal is the deeds, then they would be more important. But our Sages tell us that the thought processes which lead to the deeds are of primary concern. Being immersed in Torah has an absolute value in itself. Thus, Rabbi Kook writes:

“The thought of t’shuva transforms all transgressions and the darkness they cause, along with their spiritual bitterness and stains, into visions of joy and comfort, for it is through these contemplations that a person is filled with a deep feeling of hatred for evil, and the love of goodness is increased within him with a powerful force” (Orot HaT’shuva, 7:1).

T’shuva can be dissected into two different realms. There is the nitty-gritty t’shuva of mending an actual deed, and there is the thought process which precedes the action. The value of these thoughts is not to be measured according to the activities which they inspire. For instance, a person may decide that he wants to be righteous. But when the person tries to translate this thought into action, he finds himself overwhelmed. To be righteous, he has to get up early in the morning to pray. He has to stop doing a host of forbidden deeds. He has to watch what he says, and watch what he eats. Before he even begins, his will is broken. Though his wish to do t’shuva was sincere, he couldn’t find the inner strength to actualize his thoughts into deeds.

Rabbi Kook says that all is not lost. This person’s original idea to do t’shuva stemmed from the deepest recesses of the soul, where it was inspired by the spiritual waves of t’shuva which encircle the world. Thus he has already been touched by t’shuva’s cleansing streams. In effect, he has boarded the boat. Though his will power may be weak at the moment, his soul is longing for God.

“Through the contemplations of t’shuva, a person hears the voice of God calling him from the Torah and from the heart, from the world and all it contains. The will for good is fortified within him. The body itself, which causes transgression, becomes more and more purified until the thought of t’shuva pervades it” (Ibid, 7:5).

In the beginning of his t’shuva journey, a person must realize the absolute value of his initial inspiration. He has to find a new way of judging the value of things, not always looking for concrete benefits or results. When a person undertakes t’shuva, his thoughts weigh as much as his deeds. T’shuva is not just a process of do’s and don’ts, but rather a conscious and subconscious overhaul of an individual’s thought processes and emotions. Already by thinking about t’shuva one is engaged in it. As the saying goes: you are what you think.

“Even the thought of t’shuva brings great healing. However, the soul can only find full freedom when this potential t’shuva is actualized. Nonetheless, since the contemplation is bound up with the longing for t’shuva, there is no cause for dismay. God will certainly provide all of the means necessary for complete repentance, which brightens all darkness with its light… ‘A broken and contrite heart, O God, Thou will not despise’” (Ibid. Tehillim, 51;19).

“Even the thought of t’shuva brings great healing. However, the soul can only find full freedom when this potential t’shuva is actualized. Nonetheless, since the contemplation is bound up with the longing for t’shuva, there is no cause for dismay. God will certainly provide all of the means necessary for complete repentance, which brightens all darkness with its light… ‘A broken and contrite heart, O God, Thou will not despise’” (Ibid. Tehillim, 51;19).

When we recognize the value of our thoughts, we discover a very encouraging concept. One needn’t despair when confronted by the often difficult changes which t’shuva demands. This is especially true in the initial stages before a person’s increasing love for G-d makes all difficulties and sacrifices seem small. Even if a person cannot immediately redress all of his wrongdoings, he should know that there is a great value in just wanting to be good. One can take comfort that he wants to be a better person. With God’s help, he will also be able to actualize his yearnings. But in the meantime, just thinking good thoughts is already strengthening his inner self and the world.

This is also why t’shuva can come in a second. Just the thought of t’shuva is t’shuva itself (Kiddushin 49B). Thoughts of t’shuva are themselves uplifting. The actual mending of activities is only a second stage. This knowledge can give a person the strength to continue through difficult times. Rabbi Kook writes:

“To the extent that someone is aware of his transgressions, the light of t’shuva shines lucidly on his soul. Even if at the moment, he lacks the steadfastness to repent in his heart and will, the light of t’shuva hovers over him and works to renew his inner self. The barriers to t’shuva weaken in strength, and the blemishes they cause are diminished to the degree that the person recognizes them and longs to erase them. Because of this, the light of t’shuva starts to shine on him, and the holiness of the transcendental joy fills his soul. Gates which were closed open before him, and in the end, he will achieve the exalted rung where all obstacles will be leveled. Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low; and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain” (. Yisheyahu, 40:4. Orot HaT’shuva, 15:7).

A few examples may help illustrate this idea. Individual t’shuva includes rectifying transgressions and improving character traits. Let’s suppose that Joseph has stolen a laptop computer from Reuven who lives two thousand miles away. At the moment, even though Joseph wants to return the computer, he is unable to make the trip. This is a barrier to t’shuva. Or in a case where Reuven lives just across the street, it may be that Joseph is too embarrassed to admit his theft. Until he strengthens his will to do t’shuva, musters his inner courage, and swallows his pride, Joseph’s t’shuva will be delayed. Regarding character traits, let’s say that Joseph is an angry person. He is angry at his parents, at his wife and children, he is angry at his boss and at the neighbor down the street. It may take a considerable amount of introspection, and a serious course of Torah study, before he can transform his anger into love. But even if this barrier should seem insurmountable to him, he should take comfort in knowing that once the process of t’shuva has started, God’s help is ever near.

“When a person truly longs for t’shuva, he may be prevented by many barriers, such as unclear beliefs, physical weakness, or the inability to correct wrongs which he has inflicted on other people. The barrier may be considerable, and the person will feel remorse because he understands the weighty obligation to perfect his ways, in the most complete manner possible. However, since his longing for t’shuva is firm, even if he cannot immediately overcome all of the obstacles, he must know that the desire for t’shuva itself engenders purity and holiness, and not be put off by barriers which stand in his way. He should endeavor to seize every spiritual ascent available to him, in line with the holiness of his soul and its holy desire” (Ibid, 17:2).

In dealing with his anger, it may be that Joseph lacks the determination or courage to have a heart-to-heart talk with his boss. Or perhaps, he is afraid of losing his job. So let him begin with his parents or wife. With each step he takes, he will find greater courage for the stages ahead. And if his Pandora’s Box of anger is too threatening for him to open at all, let him turn to redress other matters more in his reach, with the faith that a more complete t’shuva will come.

“One must strengthen one’s faith in the power of t’shuva, and feel secure that in the thought of t’shuva alone, one perfects himself and the world. After every thought of t’shuva, a person will certainly feel happier and more at peace than he had in the past. This applies even more if one is determined to do t’shuva, and if he has made a commitment to Torah, its wisdom, and to the fear of God. The highest joy comes when the love of God pulses through his being. He must comfort himself and console his outcast soul, and strengthen himself in every way he can, for the word of God assures, ‘As one whom his mother comforts, so I will comfort you.’ (Yisheyahu, 66:13)

“If he discovers sins he committed against others, and his strength is too feeble to correct them, one should not despair at all, thinking that t’shuva cannot help. For the sins which he has committed against God and repented over, they have already been forgiven. Thus, it should be viewed that the sins which are lacking atonement are outweighed by the t’shuva he was able to do. Still, he must be very careful not to transgress against anyone, and he must strive with great wisdom and courage to address all of the wrongs from the past, ‘Deliver thyself like a gazelle from the hand of the hunter, and like a bird from the hand of the fowler’ (Mishle, 6:5). However, let depression not overcome him because of the things he was unable to redress. Let him rather strengthen himself in the fortress of Torah, and in the service of God, with all of his heart, in happiness, reverence, and love” (Orot HaT’shuva, 7:6).

Even though a person has not yet been able to rectify every wrong against his fellow man, every thought of t’shuva has inestimable value. “Even the minutest measure of t’shuva awakens in the soul, and in the world, a great measure of holiness” (Ibid, 14:4).

The difficulty in mending the transgressions of the past should never bring a person to despair. For even if the thought of t’shuva is still undeveloped, even if one’s desire to do good contains a mixture of unrefined motives, Rabbi Kook assures us that its basic inner holiness is worth all of the wealth in the world.

DON’T WORRY! BE HAPPY!

Amongst the many eye-opening revelations on t’shuva in Rabbi Kook’s writings, one concept is especially staggering in its profundity. Usually, we think that a process is completed when it reaches its end. We experience a feeling of satisfaction when we finish a project. An underlying tension often accompanies our work until it is accomplished. This is because the final goal is considered more important than the means.

Most people feel the same way about t’shuva. Until the process of t’shuva is complete, they feel unhappy, anxious, overwhelmed with the wrongdoings which they have been unable to redress. Rabbi Kook tells us that this perspective is wrong. When it comes to t’shuva, the goal is not the most important thing. It is the means which counts. What matters the most is the striving for perfection, for the striving for perfection is perfection itself. He writes:

“If not for the contemplation of t’shuva, and the comfort and security which come with it, a person would be unable to find rest, and spiritual life could not develop in the world. Man’s moral sense demands justice, goodness, and perfection. Yet how very distant is moral perfection from man’s actualization, and how feeble he is in directing his behavior toward the pure ideal of absolute justice. How can he aspire to that which is beyond his reach? For this, t’shuva comes as a part of man’s nature. It is t’shuva which perfects him. If a man is constantly prone to transgress, and to have difficulties in maintaining just and moral ideals, this does not blemish his perfection, since the principle foundation of his perfection is the constant longing and desire for perfection. This yearning is the foundation of t’shuva, which constantly orchestrates man’s path in life and truly perfects him” (Orot Ha’Tshuva, 5:6. The Art of T’shuva, Ch.5).

Dear reader, please note: if you are not yet a tzaddik, you need not be depressed. Success in t’shuva is not measured by the final score at the end of the game. It is measured by the playing. The striving for good is goodness itself. The striving for atonement is atonement. The striving for perfection is what perfects, in and of itself.

King Solomon teaches that no man is free of sin: “For there is not a just man on earth that does good and never sins” (Kohelet, 7:20). Transgression is part of the fabric of life. Since we are a part of this world, we too are subject to “system failure” or sin. Even the righteous occasionally succumb to temptation. Thus, until the days of Mashiach, an ideal, sinless existence is out of man’s reach.

An illustration may help make this concept clearer. On Yom Kippur, we are like angels. We don’t eat, we don’t drink. All day long we pray for atonement from all of our sins. At the end of the day, with the final blast of the shofar, we are cleansed. But in the very next moment, as we pray the evening service, we once again ask God to forgive us. Forgive us for what? The whole day we have acted like angels. Our sins were whitened as snow. In the few seconds between the end of Yom Kippur and the evening prayer, what sin did we do? Maybe at the beginning of the evening prayer, exhausted by the fast, we didn’t concentrate on our words. Maybe our prayers on Yom Kippur were half-hearted, as if repeating last year’s cassette. Maybe, we forgot to ask forgiveness for some of our sins.